A Second Look at Long-Term Imprisonment in Michigan

Michigan imprisons 35,000 people serving terms from one year to life without parole. While the state has experienced a 38% decline in its prison population since 2006, Michigan’s sentencing policies still result in harsh punishments and excessive prison terms for residents.

Related to: Sentencing Reform, State Advocacy, Incarceration

Michigan imprisons 35,000 people serving terms from one year to life without parole.1 While the state has experienced a 38% decline in its prison population since 2006,2 Michigan’s sentencing policies still result in harsh punishments and excessive prison terms for residents. Nationwide, legal experts, lawmakers and prosecutors are promoting opportunities to review lengthy sentences to account for criminological evidence finding unduly long sentences are unnecessary because people age out of crime, and the general threat of long-term imprisonment is an ineffective deterrent. Michigan’s adoption of a “second look” at long sentences would ensure a more effective use of public resources, address the state’s high rates of racial disparity in imprisonment, and further reduce the large prison population.

Time Served

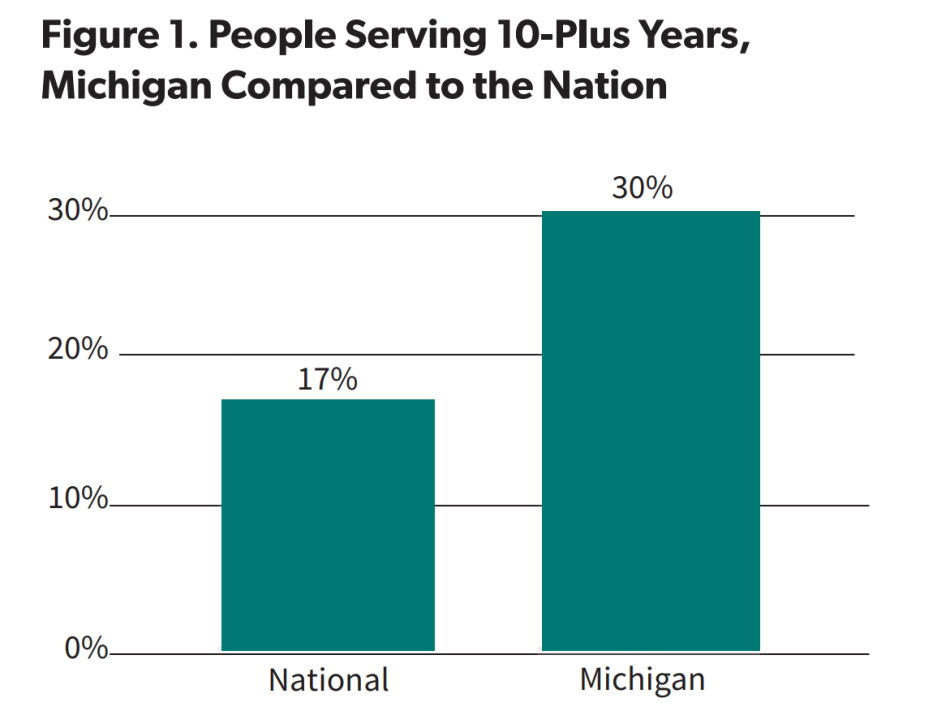

30 Percent of Michigan’s Prison Population Have Served 10 Years or More, Far Above National Average

The average criminal career lasts approximately 10 years,3 with recidivism rates dropping considerably at around this period.4 Yet, 30% of imprisoned Michiganders have already served 10 years and nearly one in 5 have already served 15 years. In comparison to other states, Michigan has a greater share of people who have served over ten years.5

38% of People Who Have Served 10 Years or More were 25 or Younger at the Time of Their Crime

More than one third of those who have served at least 10 years were relatively young (i.e., 25 or younger) at the time of the crime. This is noteworthy because established brain science documents that individuals do not attain full neuroscientific maturity until their mid twenties; this absence of full maturity bears directly on crime-related decision making because of its impact on risk taking.6 Specifically, calculations of risk and reward are highly inaccurate until one’s mid-twenties, compounded by the fact that late adolescence and emerging adulthood years are heavily influenced by negative peer pressure.7 Most young people who commit violent offenses live in extreme poverty and within communities that are unsafe and poorly protected.8

Racial Disparities are Substantial

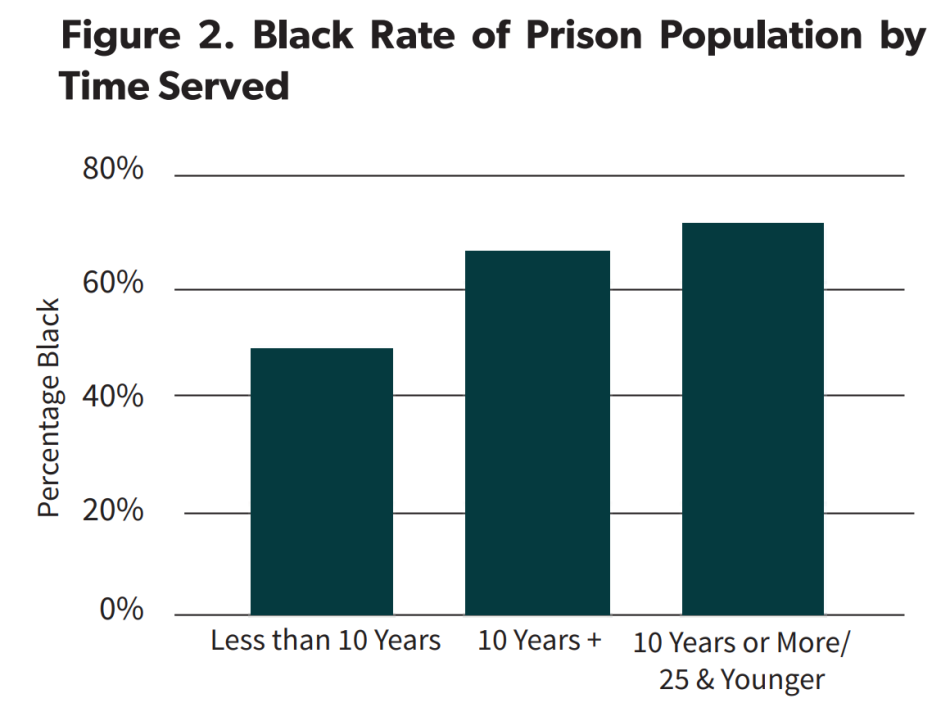

As with the entire criminal legal system, Black Americans are overrepresented in the population serving longer sentences. More than half of the prison population in Michigan is Black,9 and racial disparities are even more heavily skewed among the imprisoned population who are young (65% Black) and those serving terms over 10 years (70% Black).

As shown below, nearly half (48%) of people who have been incarcerated for less than 10 years are Black, but 63% of people who have served 10 years or more are Black. Even more troubling is that among those who were young and have already served 10 years, 70% are Black.

Women comprise a small share of the overall prison population (5%) and are a small share of the overall group of people having served at least 10 years (3%), but half of them are Black. Over one third of imprisoned women have been sentenced to at least 10 years, including 203 women sentenced to life.10 Among women serving life, 46% are Black and one third were under 26 at the time of their crime.

Life Imprisonment

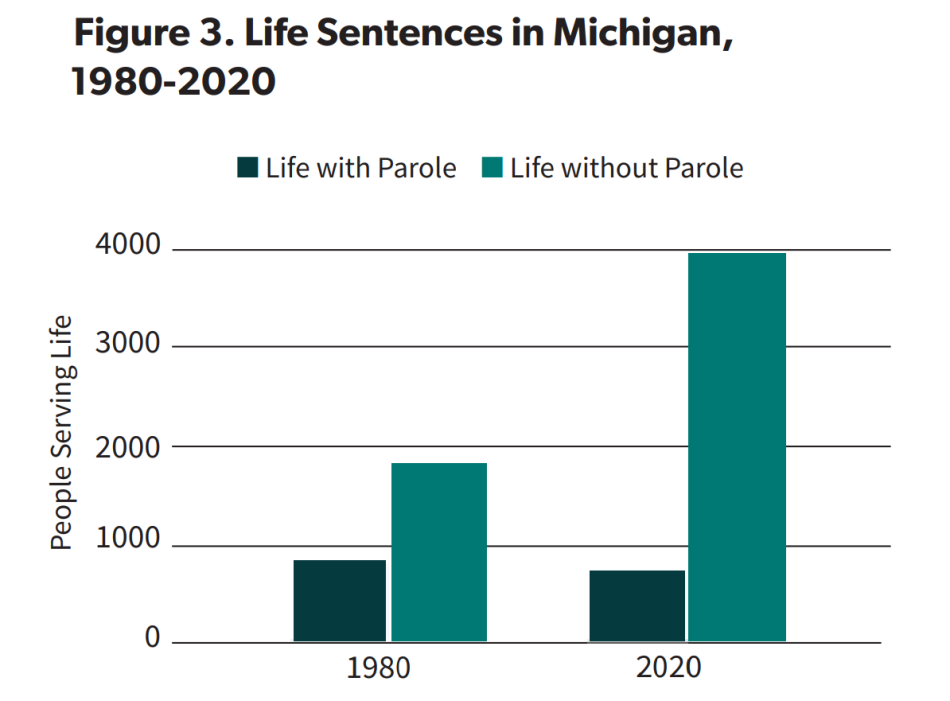

Approximately 5,000 people are serving life sentences in Michigan and three quarters of them are ineligible for parole. Michigan has the fifth-largest population of people serving life without parole (LWOP) in the United States.11

The use of life sentences has continued even as the state’s overall prison population has begun to decline. In particular, LWOP sentences have quintupled since 1980, from 697 reported individuals serving LWOP sentences in 1980 to 3,882 in 2020.12

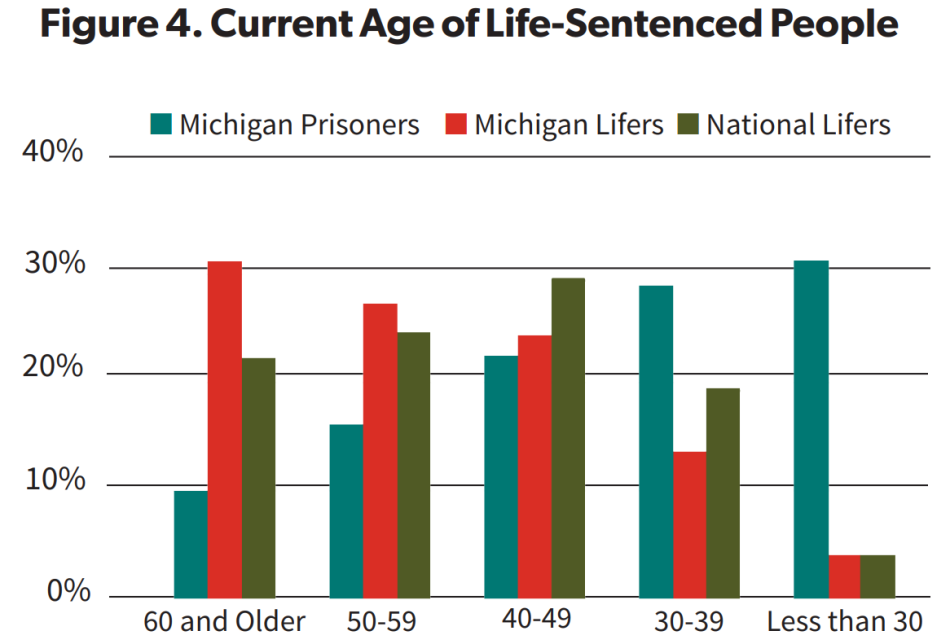

People serving life are significantly older than the general prison population; nearly half are at least 50 years old. As of 2020, 10% of the overall prison population was at least 60 but 31% of the life-sentenced population was 60 and older.

Age is an important factor to consider, as aging in prison is an expensive investment for states, particularly considering the low recidivism rate among older persons, even if they committed violence in the past.13 The annual per-person cost of imprisonment in Michigan ranges from $34,000 to $48,000 depending on security level. Beyond these costs are medical costs, which rise with age, running about $8,000 for medical, dental, and psychological services per incarcerated person.14

| Sentence Length | Number 50 and Older | Total | Percent 50 and Older of Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20-29 | 1,095 | 3,537 | 31% |

| 30-39 | 461 | 1,344 | 34% |

| 40-49 | 294 | 608 | 48% |

| 50-100 | 297 | 492 | 60% |

| LIFE | 2,650 | 4,839 | 55% |

Recidivism is Highly Unlikely Among People Released from Long-Term Imprisonment

It is a criminological fact that violent conduct occurs in predictable ways over the life course, with proclivity toward criminal behavior among at-risk individuals rising from late adolescence to the mid-20s and dropping precipitously after. Even among people who commit multiple serious crimes in young adulthood, it appears that the vast majority of them will stop committing crime by the end of their 30s.15 Research establishes that it is erroneous to conclude that recidivism is the result of insufficiently short prison sentences.

| 1. | All data used in this report were obtained from the Michigan Department of Corrections and are valid as of May, 2021. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Ghandnoosh, N. (2023) Ending 50 Years of Mass Incarceration: Urgent Reform Needed to Protect Future Generations. The Sentencing Project. |

| 3. | Kazemian, L. (2021). Pathways to desistance from crime among juveniles and adults: Applications to criminal justice policy and practice. National Institute of Justice; Blumstein, A., & Piquero, A. (2007). Restore rationality to sentencing policy. Criminology & Public Policy, 6(4), 679-687. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745- 9133.2007.00463.x; Kazemian, L., & Farrington, D. P. (2018). Advancing knowledge about residual criminal careers: A follow-up to age 56 from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. Journal of Criminal Justice, 57, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jcrimjus.2018.03.001; Piquero, A., Hawkins, J., & Kazemian, L. (2012). Criminal career patterns. In R. Loeber & D. P. Farrington (Eds.), From juvenile delinquency to adult crime: Criminal careers, justice policy, and prevention (pp. 14–46). Oxford University Press. |

| 4. | Antenangeli, L., & Durose, M.R. (2021). Recidivism of prisoners released in 24 states in 2008: A 10- year follow-up period (2008–2018). Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 5. | A 45-state average of states reveals that 17% of incarcerated people have served over 10 years. See: Ghandnoosh, N. & Nellis, A. (2022). How many people are spending over a decade in prison? The Sentencing Project. Data Sources: United States. Bureau of Justice Statistics. National Corrections Reporting Program, 1991-2019: Selected Variables. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2021-07-15; Michigan Department of Corrections. |

| 6. | Casey, B. J., Simmons, C., Somerville, L. H., & Baskin-Sommers, A. (2022). Making the sentencing case: Psychological and Neuroscientific evidence for expanding age of youthful offenders. Annual Review of Criminology, 5, 321-343. |

| 7. | Bersani, B., Laub, J., & Western, B. (2019). Thinking about emerging adults and violent crime. Columbia University Justice Lab; Kaiser, L. (2012). Six facts about crime and the adolescent brain. Michigan Public Radio. |

| 8. | Anderson, E. A. (1999). Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. W.W. Norton & Company; Bernard, T. J. (1990). Angry aggression among the ‘truly disadvantaged’. Criminology, 28(1), 73–96; Comfort, M. (2012). “It was basically college to us”: Poverty, prison, and emerging adulthood. Journal of Poverty, 16(3): 308–322. |

| 9. | Nellis, A. (2021). Color of justice: Disparity in state prisons. The Sentencing Project. |

| 10. | |

| 11. | Nellis, A. (2021). No end in sight: America’s enduring reliance on life imprisonment. The Sentencing Project. |

| 12. | Nellis, A. (2016). Life goes on: The historic rise in life sentences in America. The Sentencing Project. |

| 13. | Antenangeli, L. & Durose, M.R. (2021). Recidivism of prisoners released in 24 states in 2008: A 10-year follow up. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 14. | Michigan Department of Corrections (2022). Report to the Legislature; Michigan Department of Corrections. 2021 Statistical report. |

| 15. | Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2003). Shared beginnings, divergent lives: Delinquent boys to age 70. Harvard University Press; Neil, R. & Sampson, R. (2021). The birth lottery of history: Arrest over the life course of multiple cohorts coming of age, 1995 2018. American Journal of Sociology. 126(5): 1127–1178. |