Baltimore’s Youth Justice by the Numbers

Based on data by the Baltimore Police Department, youth arrests have not only decreased significantly, but the proportion of youth involved in total arrests has also diminished.

Related to: Youth Justice

The Sentencing Project’s recent ‘Youth Justice by the Numbers’ report1 found that youth arrests nationwide declined by 75% between 2000 and 2022, unraveling the prevailing narrative that youth offending is out of control or higher than ever. Much of this false narrative is being driven by media who often misunderstand what the data is telling us and officials who rely on punitive measures.

To be clear, any youth crime is a concern. The purpose of this report is to correct the inaccurate assertions from Baltimore’s elected prosecutor and others who would state that youth crime is “out of control.” This is simply not true based on the data made available. It’s time to tell the truth about Baltimore’s youth.

In July 2024, 51 young people under the age of 18 were arrested in the city of Baltimore.2 As shown in the figure above, there are significant monthly fluctuations in arrests; annual averages (shown by the dotted green line) have been relatively steady from 2020 to 2024.

These data come from the Baltimore Police Department’s (BPD) Juvenile Booking Data Analysis Unit which provides a monthly report on arrests for people under 18. The reports are approximately 30 pages and categorize arrests according to age, gender, time of day, police district, and charge.

Soon after the July 2024 report was issued, Baltimore City State’s Attorney Ivan Bates asserted, “I see the juvenile crime numbers. Juvenile crime is out of control.”3 This is not an accurate reflection of the data we have available to us.

Because of the BPD’s reports, we know that the assertion of a youth crime wave from the city’s elected prosecutor is not backed by evidence. Arrests were lower in July 2024 than June, which in turn was lower than in May. The number of arrests in April, May, June and July 2024 was lower than the same months in 2023.

Taking a longer term perspective, the 458 youth arrests through July 31, 2024 is roughly half the total (976 youth arrests) versus the same time person for 2019, showing a significant decline over the last five years. Despite the positive trends, it can be tempting to cherry-pick data points to suggest a crisis. For example, arrests for assault and robbery (which is just one charge) are up while arrests for handgun possession are down. This report aims to paint a succinct and accurate portrait of Baltimore’s crime issues and the role that youth play in that crime.

Youth Arrests Are Down in Baltimore City

Figure 1 shows monthly arrests of people under 18 in the city of Baltimore from January 2016 through June 2024. Because monthly variations in those counts (in gray) make the patterns hard to see, the graph’s dotted light green line also indicates annual averages for 2016 through 2024.

- Overall youth arrests are significantly lower post-pandemic than pre-pandemic. In 2019, more than 130 youth were arrested in a typical month (itself a sharply lower average than 2017). In 2024, the monthly average number of arrests has been 65, roughly half that number.

- Youth arrests plunged during the pandemic, falling to 29 in December 2020. In 2021, 52 youth were arrested in an average month, the lowest total of the years reviewed. There have been increases since those nadirs, but the totals remain much lower than from before the pandemic.

Youth Arrests are a Small Proportion of Arrests in Baltimore City

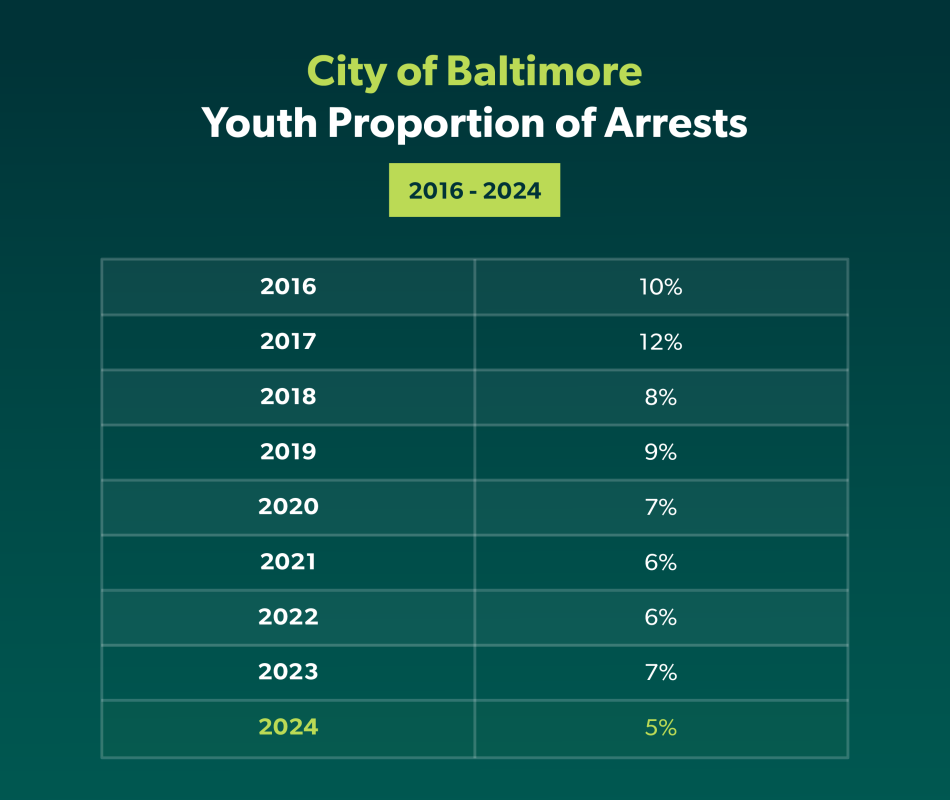

An assertion that “juvenile crime is out of control” further implies that youth are responsible for a disproportionate and growing proportion of arrests. The available data show that the opposite is true: Baltimore’s youth are responsible for a small and shrinking proportion of total arrests.4

Youth between the ages of 10 and 17 comprise 8% of Baltimore’s population,5 and thus far in 2024, have comprised roughly 5% of arrests in the city. This is a smaller proportion than any year since 2016, when this analysis began.

Violent Offenses are Down In Baltimore

Viewing crime in the city as a whole, not only youth arrests, fewer violent offenses were reported to the Baltimore Police Department in 2023 than 2022, and that decline has continued in 2024, year to date.6 As shown in the figure below, total violent offenses have fluctuated between 2015 and 2024, but peaked in 2017. Recent years’ rates have been lower than those from before the pandemic.

The Car Theft Spike Was Real, but Has Waned

Baltimore experienced a car theft spike which peaked in the summer of 2023, driven by an increase in thefts of Kias and Hyndais, described by Car and Driver magazine (among others) as “easily stolen.”7 Incident reports do not provide any information about who committed those offenses. From 2018 to 2022, roughly 300 cars were reported stolen per month in Baltimore.8 An increase that began in the summer of 2022 spiked through the first half of 2023, peaking at over 1,600 — more than five times the typical average in prior years. That number has fallen steadily since, averaging 550 stolen cars per month thus far in 2024 — still well above the prior average but showing a promising trend.

Conclusion

Given the enormous volume of data, it is easy to cherry pick numbers to show increases or decreases. However, an assertion that youth crime is out of control must be backed by evidence that (a) overall youth offending is up to a significant degree or that (b) the city’s crime rate is increasing and that youth are likely responsible for that increase. Neither of those concepts are true.

It’s time to tell the truth about Baltimore’s youth.

| 1. | Rovner, J. (2024). “Youth justice by the numbers.” The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Baltimore City Police Department, Juvenile Booking Data Analysis Unit (2024). “Juvenile arrest monthly report, July 1, 2024 to July 31, 2024.” Data throughout this report are derived from this and prior reports dating back to the report for January 2018. |

| 3. | Simms, B. (2024). Youth violence concerns Baltimore prosecutor Ivan Bates. Baltimore: WBALTV-11. |

| 4. | Youth arrests: Baltimore City Police Department, Juvenile Booking Data Analysis Unit (2024, Aug. 21). “Juvenile arrest monthly report, July 1, 2024 to July 31, 2024.” Total arrests: Open Baltimore dashboard. Last accessed Aug. 27, 2024. |

| 5. | Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A. and Kang, W. (2021). Easy Access to Juvenile Populations: 1990-2020. |

| 6. | City of Baltimore. Untitled Baltimore crime dashboard. Last accessed Aug. 27, 2024. |

| 7. | Blanco, S. (2023). “Hyundai/Kia will pay owners $200 million over easily stolen cars.” CarandDriver.com. |

| 8. | City of Baltimore. Untitled Baltimore crime dashboard. Last accessed Aug. 27, 2024. |