California Should Restore Voting Rights to Over 97,000 Citizens

More than 97,000 California citizens cannot vote while serving a prison term for a felony conviction in any state, federal, or local facility.

Related to: Voting Rights, Racial Justice, Collateral Consequences

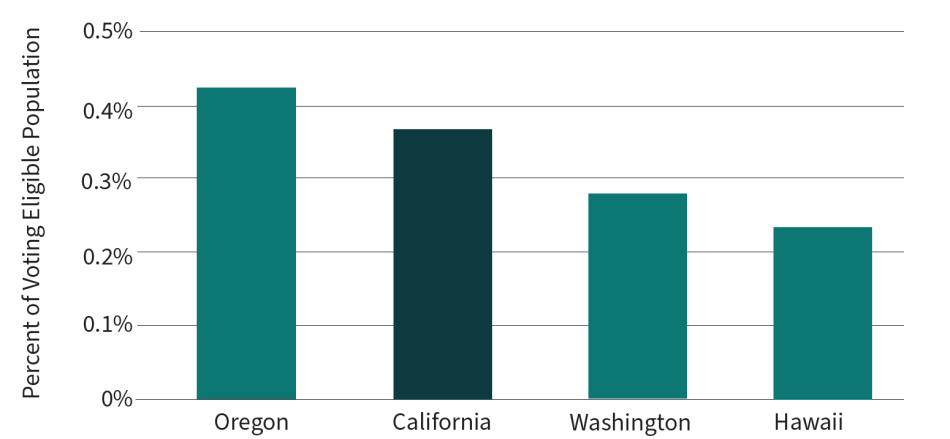

More than 97,000 California citizens cannot vote while serving a prison term for a felony conviction in any state, federal, or local facility – a result of California’s constitution.1 Because of its high incarceration rate, California’s disenfranchisement rate ranks second highest in the region among states that ban citizens from voting while in prison but reinstate voting rights upon release. Only Oregon prohibits a higher share of its citizens from voting while serving a sentence in prison for a felony conviction.

Voter Exclusion Due to Imprisonment for Felony Convictions in Select Pacific States, 2024

Source: Uggen, C, Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R. & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked Out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

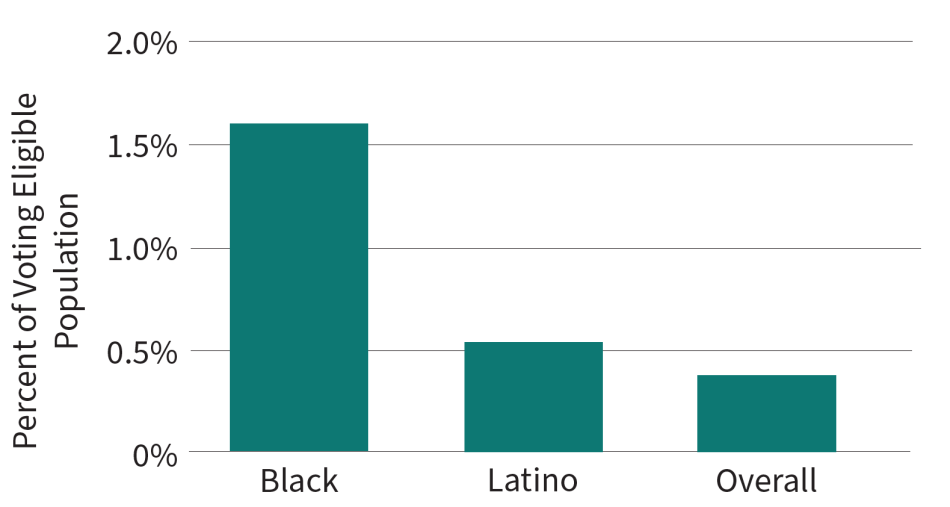

California’s voting ban results in stark racial injustices in ballot access. Voting-eligible Black Californians are over five and a half times as likely as non-Black Californians to lose their right to vote due to serving a prison sentence for a felony conviction. The disenfranchisement rate of California’s voting-eligible Latino population is almost twice that of the non-Latino voting-eligible population. Such racial and ethnic disparities contradict California’s constitution that “all political power is inherent in the people.”2

To ameliorate this racial injustice and protect its democratic values, California should follow the lead of Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC, and extend voting rights to all citizens with felony convictions, including persons completing their sentence in prison.

Voter Exclusion Rates in California by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Uggen, C, Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R. & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked Out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

Racial Injustice in California’s Criminal Legal System Causes Disparities in Voter Disenfranchisement

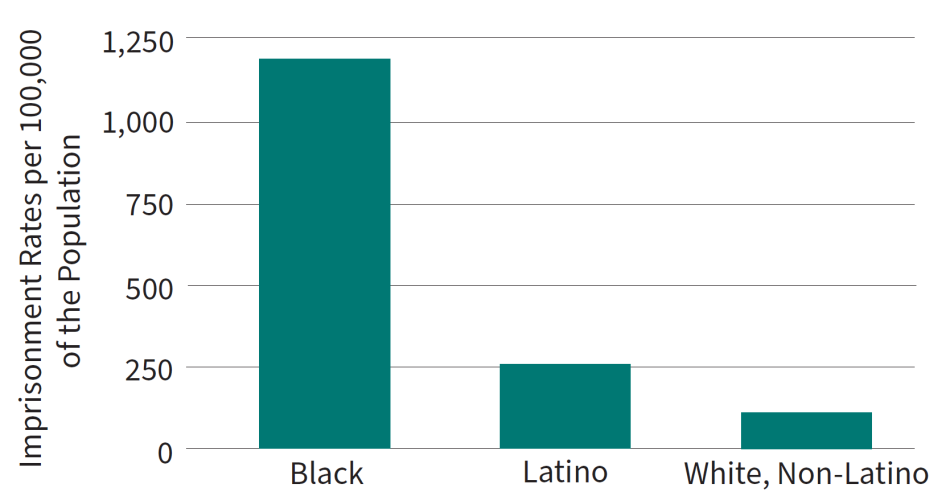

Being denied the right to vote is particularly acute for Black Californians due to their disproportionate incarceration. Black Californians make up only 5% of the state’s general population, but 27% of individuals incarcerated in state prisons.3 They are incarcerated in state prisons at over nine times the rate of white Californians. Latino Californians are also disproportionately incarcerated in prisons, at twice the rate of white Californians.

Imprisonment Rates in California by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

California Department of Corrections (2025). In-Custody Dashboard Offender Data Points, month-end February 2025. California Department of Corrections; U.S. Census Bureau (2023). American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables – table B03002. U.S. Census Bureau.

Such disparities in incarceration go beyond differences in criminal offending and result from differential practices throughout California’s criminal legal system. The following examples illustrate criminal justice practices that have differential effects on racial and ethnic groups.

Policing:

- Researchers at Stanford found that Oakland Police Department officers disproportionately stopped, searched, and arrested Black residents compared to white residents. Out of more than 28,000 traffic and pedestrian stops conducted from April 2013 to 2014 in Oakland, California, 60% of the stops were of Black residents. One in five stops resulted in Black men being searched (vs. 1 in 20 for white men) and one in six Black men who were stopped/searched were arrested (vs. 1 in 14 for white men). This racial disparity remained significant after controlling for factors relevant to officer decision-making, crime rates, and the underlying racial and socioeconomic demographics.4

- Black individuals were more than twice as likely to be arrested than white individuals in all but four counties in California, according to research conducted by the Public Policy Institute of California. These racial disparities tended to be most severe in affluent counties where Black Californians make up a smaller percentage of the population.5

Sentencing

- In a comparison of comparable drug-related cases, Black males were 17% more likely to receive a prison sentence than white males after California passed Proposition 36 in 2000, according to a study in the Journal of Quantitative Criminology. Proposition 36 permitted treatment and community supervision instead of incarceration.6

- Black Americans are especially over-represented among people serving the longest sentences. For example, more than 45% of individuals with three-strike sentencing enhancements were Black, while Black Californians made up 28% of all individuals in state prisons and only 5% of the state’s residents, according to research by UC Berkeley’s California Policy Lab. As of 2022, half of all people incarcerated under the three-strike law have been incarcerated for more than 20 years.7

Racial disparity in incarceration dilutes the political voice of people of color in California. Extremely lengthy sentences, including life without parole, also disproportionately exclude people of color from the ballot box.8 California should safeguard democratic rights and not allow a racially disparate criminal legal system to restrict voting rights.

Supporting Voting Rights Improves Public Safety

Research shows that an opportunity to participate in democracy has the potential to reduce one’s perceived status as an “outsider.” The act of voting can have a meaningful and sustaining positive influence on justice-impacted citizens by making them feel they belong to a community.9 Having a say and a stake in the life and well-being of your community is at the heart of our democracy.

Re-enfranchisement can facilitate successful re-entry and reduce recidivism. The University of Minnesota’s Christopher Uggen and New York University’s Jeff Manza find that among people with a prior arrest, there are “consistent differences between voters and non-voters in rates of subsequent arrest, incarceration, and self-reported criminal behavior.”10 Research also suggests having the right to vote immediately after incarceration matters for public safety. Individuals in states which continued to restrict the right to vote after incarceration were found to have a higher likelihood of experiencing a subsequent arrest compared to individuals in states who had their voting rights restored post-incarceration.11 Given re-enfranchisement misinformation and obstacles facing justice-impacted citizens upon re-entry into our communities, one path to bolster public safety and promote prosocial identities is to preserve voting rights during incarceration.

Allowing people to vote, including persons completing felony sentences in prisons or jails, prepares them for more successful reentry and bolsters a civic identity. By ending disenfranchisement as a consequence of incarceration, California can improve public safety while also promoting reintegrative prosocial behaviors.

California Can Strengthen its Democracy by Restoring the Right to Vote

Since 1997, 26 states and the District of Columbia have expanded voting rights to people living with felony convictions. As a result, over 2 million Americans have regained the right to vote.12 California officials expanded voting rights to justice-impacted residents through several reforms.

In 2014, California restored voting rights to their justice-impacted citizens who were on any form of community supervision with the exception of parole. In 2016, a measure signed by Governor Jerry Brown expanded voting rights under the state’s Realignment Act13 and authorized voting rights for an estimated 50,000 people serving felony sentences in county jails.14 Four years later, this momentum continued with voter-eligible Californians passing Proposition 17, a state constitutional amendment which restored voting rights to every Californian exiting prison. Almost 60% of voters – roughly 10 million people – said “yes” to re-enfranchising their fellow citizens who were on parole.15 Yet, California continues to disenfranchise an entire group of their citizens: those serving a sentence in prison or jail due to a felony conviction.

Excluding an entire population of people from exercising their right to vote erodes democracy and disregards the principles of “One Person, One Vote.” It does not encapsulate California’s constitution that “all political power is inherent in the people.”16 When the state of California takes away its citizens’ ability to vote, it also removes an important avenue for them, especially for people of color, to advocate for their own needs and the needs of their communities.

Blocking access to the ballot box betrays the democratic process and the voice of the people. California should strengthen its democracy and advance racial justice by re-enfranchising its entire voting-eligible population. California should carry forward the momentum of the past decade by joining Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC, in ensuring all of their citizens can participate in our democratic process.

| 1. | Uggen, C, Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R. & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked Out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project |

|---|---|

| 2. | California Legislative Information. (n.d.). California constitution. |

| 3. | California Department of Corrections. (2025). In-Custody Dashboard Offender Data Points, month-end February 2025. California Department of Corrections; U.S. Census Bureau (2023). American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables – table B03002. U.S. Census Bureau. |

| 4. | Hetey, R. C., Monin, B., Maitreyi, A., & Eberhardt, J. L. (2016, June 15). Data for change: A statistical analysis of police stops, searches, handcuffings, and arrests in Oakland, Calif., 2013-2014. Stanford SPARQ; Note: The statistic on being handcuffed when stopped excludes stops that resulted in an arrest. |

| 5. | Lofstrom, M., Martin, B., Goss, J., Hayes, J., & Raphael, S. (2019). Key factors in arrest trends and differences in California’s counties. Public Policy Institute of California. |

| 6. | Nicosia, N., MacDonald, J. M., & Pacula, R. L. (2016). Does mandatory diversion to drug treatment eliminate racial disparities in the incarceration of drug offenders? An examination of California’s Proposition 36. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 33(1), 179–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-016-9293-x |

| 7. | Bird, M., Gill, O., Lacoe, J., Pickard, M., Raphael, S., & Skog, A. (2022). Three strikes in California. California Policy Lab at UC Berkeley. |

| 8. | Fernandez, L. (2023, May 29). Judge finds Contra Costa county DA overcharged black defendants in watershed racial-bias ruling. Fox KTVU. |

| 9. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 10. | Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2004). Voting and subsequent crime and arrest: Evidence from a community sample. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 36(1), 193-216. |

| 11. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project. |

| 12. | Porter, N., & McLeod, M. (2023). Expanding the vote: State felony disenfranchisement reform, 1997-2023. The Sentencing Project. |

| 13. | California’s 2011 realignment policy diverted many individuals convicted of non-violent felonies from incarceration in state prisons to local jails or community supervision where individuals would report to probation officers. At the time, California law allowed people on felony probation, but not parole or prison, to vote. |

| 14. | CBS San Francisco (2016, September 16). Gov. Brown signs bill giving right to vote to thousands of felons. CBS SF Bay Area. |

| 15. | Porter, N., & McLeod, M. (2023). Expanding the vote: State felony disenfranchisement reform, 1997-2023. The Sentencing Project. |

| 16. | Porter, N., & McLeod, M. (2023). Expanding the vote: State felony disenfranchisement reform, 1997-2023. The Sentencing Project. |