Connecticut Bars Over 5,400 Citizens from Voting

Connecticut denies the right to vote to 5,400 people even after state lawmakers restored voting rights for people on parole in 2021. Almost 42% of Connecticut residents disenfranchised due to felony convictions are Black and 28% are Latino.

Related to: Voting Rights, Racial Justice, State Advocacy

Connecticut denies the right to vote to 5,400 people even after state lawmakers restored voting rights for people on parole in 2021.1 Almost 42% of Connecticut residents disenfranchised due to felony convictions are Black and 28% are Latino.2 To ameliorate this racial injustice and protect its democratic values, Connecticut lawmakers should follow the lead of Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC and extend voting rights to all citizens with felony convictions, regardless of their current incarceration status.

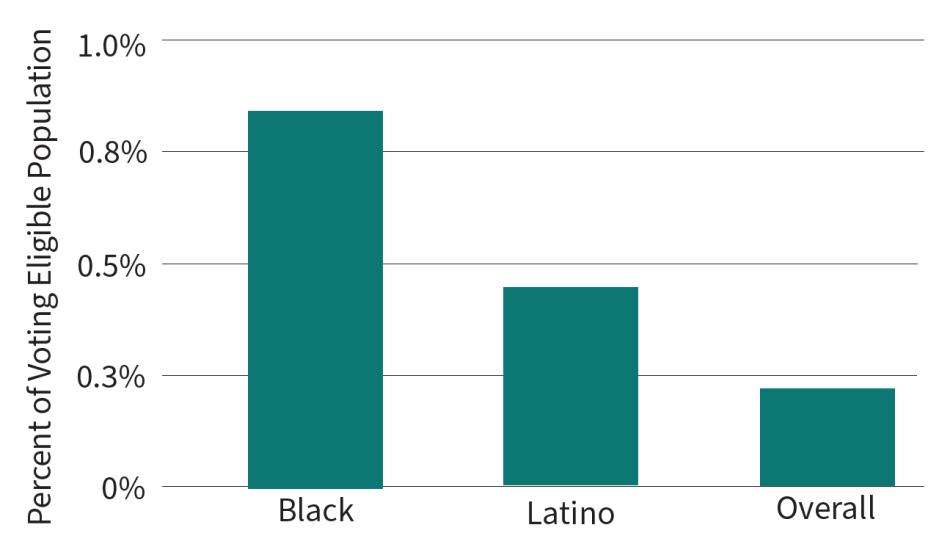

Voter Exclusion Rates in Connecticut by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Source: Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R. & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

Amongst those excluded from voting due to a felony conviction in Connecticut, Black people are excluded at a rate over six times that of non-Black people. Latino people experience similar disparities, being excluded at a rate of over 2.5 times that of non-Latino people, due to a felony conviction.

Racial Injustice Causes Disparities in Disenfranchisement

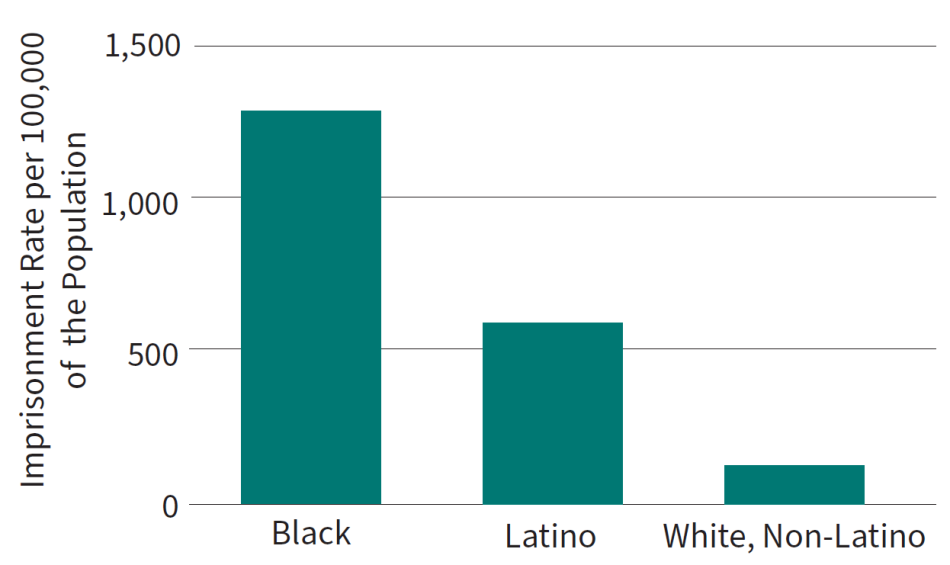

People of color are disproportionately disenfranchised in Connecticut because they are overrepresented in its criminal legal system. While Black Connecticut residents make up only 10% of Connecticut’s population, they represent 41% of the state’s incarcerated population.3 Latino people represent 18% of Connecticut’s population, and 30% of the state’s incarcerated population.4 Connecticut incarcerates Black adults at more than nine times the rate it incarcerates white adults. Connecticut incarcerates Latino adults at almost four times the rate it incarcerates white adults.5

Racial bias and discrimination in the justice system lock people of color out of the democratic process. According to the ACLU of Connecticut, racial bias in the state’s police system contributes to drivers of color being disproportionately stopped and searched.6 In 2019, the Connecticut Supreme Court—acknowledging systemic racial bias in jury selection—created a Jury Selection Task Force to study the issue and draft recommendations.7 Racial bias and discrimination in the judicial system can impact court outcomes. In Connecticut, Black and Latino individuals are convicted at higher rates (46% and 42% respectively) than white individuals (37%).8

Imprisonment Rates in Connecticut by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Sources: Connecticut Department of Corrections (2025). Population confined March 1st, 2025, table of facility by race. Connecticut Department of Corrections; U.S. Census Bureau (2023). Hispanic or Latino origin by race. American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables, table B03002. U.S. Census Bureau.

Promote Voting Rights for All Connecticut Residents

Prior to the 2021 legislation re-enfranchising people on parole, Connecticut’s felony disenfranchisement law and policy was the most regressive in the Northeast.9 While Connecticut has made progress towards addressing the legacy of Jim Crow era disenfranchisement laws, it was one of the last states in the Northeast to re-enfranchise people on parole.10

The right to vote in prison is recognized as an essential democratic practice both inside and out of the United States. In Maine and Vermont, people convicted of felonies never lose their right to vote. In both states, people in prisons can register (and remain registered) at their pre-incarceration address, and can request absentee ballots by mail.11 In 2005, the European Court of Human rights determined that bans on voting in prison violate the European Convention on Human Rights,12 while Canada, Israel, and South Africa have also ruled conviction-based voting rights restriction unconstitutional.13 In 2024, The Sentencing Project, ACLU, and Human Rights Watch found that the United States was more restrictive than over half of 136 countries surveyed regarding exclusion from the right to vote due to criminal convictions.14

Supporting Voting Rights Improves Public Safety

Research shows that an opportunity to participate in democracy has the potential to reduce one’s perceived status as an “outsider.” The act of voting can have a meaningful and sustaining positive influence on justice-impacted citizens by making them feel they belong to a community.15 Having a say and a stake in the life and well-being of your community is at the heart of our democracy.

Re-enfranchisement can facilitate successful re-entry and reduce recidivism. The University of Minnesota’s Christopher Uggen and New York University’s Jeff Manza find that among people with a prior arrest, there are “consistent differences between voters and non-voters in rates of subsequent arrest, incarceration, and self-reported criminal behavior.”16 Research also suggests having the right to vote immediately after incarceration matters for public safety. Individuals in states which continued to restrict the right to vote after incarceration were found to have a higher likelihood of experiencing a subsequent arrest compared to individuals in states who had their voting rights restored post-incarceration.17 Given re-enfranchisement misinformation and obstacles facing justice-impacted citizens upon re-entry into our communities, one path to bolster public safety and promote prosocial identities is to preserve voting rights during incarceration.

Allowing people to vote, including persons completing felony sentences in prisons or jails, prepares them for more successful reentry and bolsters a civic identity. By ending disenfranchisement as a consequence of incarceration, Connecticut can improve public safety while also promoting reintegrative prosocial behaviors.

Connecticut Can Preserve Its Democracy by Restoring the Right to Vote

Excluding an entire population of people from exercising their right to vote undermines democracy. Felony disenfranchisement creates a disconnect between lawmakers and the people they are meant to represent. In many cases, the ability to afford quality legal representation can mean the difference between a sentence of probation and prison.18 The importance of enfranchisement for people in prisons goes beyond participation in state and federal elections. For example, parents should be able to vote in their child’s school board elections, even while incarcerated.19 The goal is an engaged citizenry, regardless of where they reside.

Connecticut should join Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC in ensuring all of their citizens can participate in our democratic process. Doing so would respect Connecticut’s own state constitution, which declares that “all political power is inherent in the people, and all free governments are founded on their authority, and instituted for their benefit.”20 Connecticut should advance racial justice by re-enfranchising its entire voting age population.

| 1. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R. & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R. & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 3. | Connecticut Department of Corrections (2025). Population confined March 1st, 2025, table of facility by race. Connecticut Department of Corrections; U.S. Census Bureau (2023). Hispanic or Latino origin by race. American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables, table B03002. U.S. Census Bureau. |

| 4. | Connecticut Department of Corrections (2025). Population confined March 1st, 2025, table of facility by race. Connecticut Department of Corrections; U.S. Census Bureau (2023). Hispanic or Latino origin by race. American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables, table B03002. U.S. Census Bureau. |

| 5. | Nellis, A. (2021). The color of justice: Racial and ethnic disparity in state prisons. The Sentencing Project. |

| 6. | ACLU Connecticut. (2021). Smart justice. American Civil Liberties Union. |

| 7. | State of Connecticut v. Evan Jaron Holmes, SC 20048 (2019). https://www.jud.ct.gov/external/supapp/Cases/AROcr/CR334/334CR65.pdf |

| 8. | Criminal Justice Policy Advisory Commission. (2019). Criminal cases disposed in CT courts, 2019. State of Connecticut Division of Criminal Justice. |

| 9. | Baum, S. (2021). Voting rights restoration efforts in Connecticut. Brennan Center for Justice. |

| 10. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R. & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project; Delaware continues to disenfranchise people on parole. |

| 11. | White, A., & Nguyen, A. (2020). Locking up the vote? Evidence from Maine and Vermont on voting from prison. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. |

| 12. | Porter, N. D., & Chung, J. (2021). Voting rights in the era of mass incarceration: A primer. The Sentencing Project. |

| 13. | Porter, N. D., & Chung, J. (2021). Voting rights in the era of mass incarceration: A primer. The Sentencing Project. |

| 14. | Porter, N. D., Parker, A., Walk, T., Topaz, J., Turner, J., Smith, C., LaRonde-King, M., Pearce, S., & Ebenstein, J. (2024). Out of step: U.S. policy on voting rights in global perspective. The Sentencing Project. |

| 15. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 16. | Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2004). Voting and subsequent crime and arrest: Evidence from a community sample. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 36(1), 193-216. |

| 17. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project. |

| 18. | Liebelson, D. (2019, Sept 6). In prison, and fighting to vote. The Atlantic. |

| 19. | Liebelson, D. (2019, Sept 6). In prison, and fighting to vote. The Atlantic. |

| 20. |