Florida Bans Voting Rights of Over 960,000 Citizens

Florida surpasses every state in the nation with the largest number of U.S. citizens who cannot vote due to a felony conviction.

Related to: Voting Rights, State Advocacy

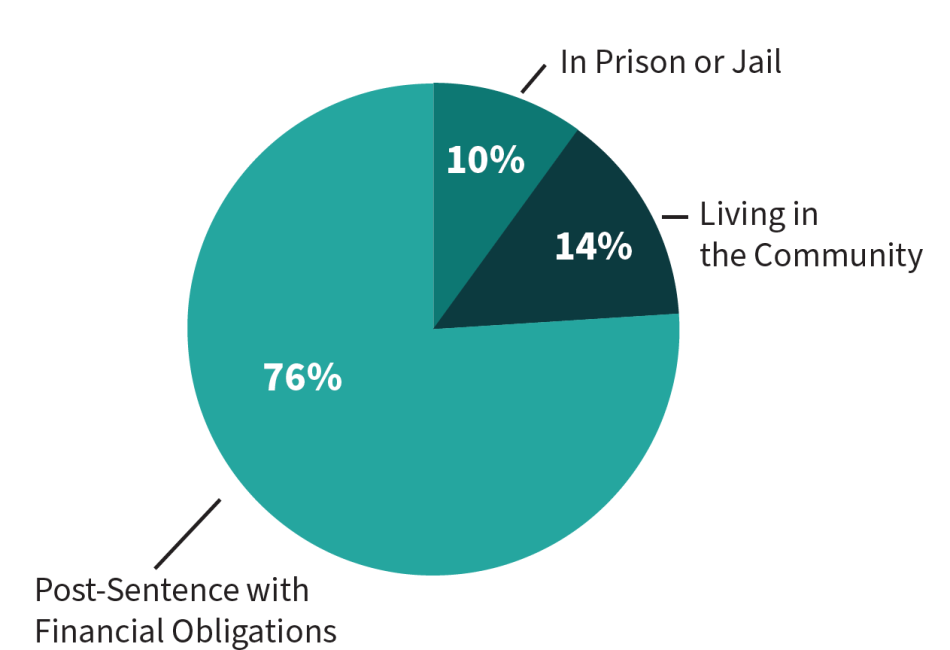

Florida surpasses every state in the nation with the largest number of U.S. citizens who cannot vote due to a felony conviction – over 960,000 Floridians.1 The overwhelming majority of this group, nearly 730,000 Florida citizens, have completed their sentence but not yet fully paid court fines, fees, costs, or restitution. They are denied access to the ballot box simply because legal financial obligations are a barrier to regaining their right to vote—a poverty penalty.2

People Denied the Right to Vote Due to a Felony Conviction in Florida, 2024

Source: Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

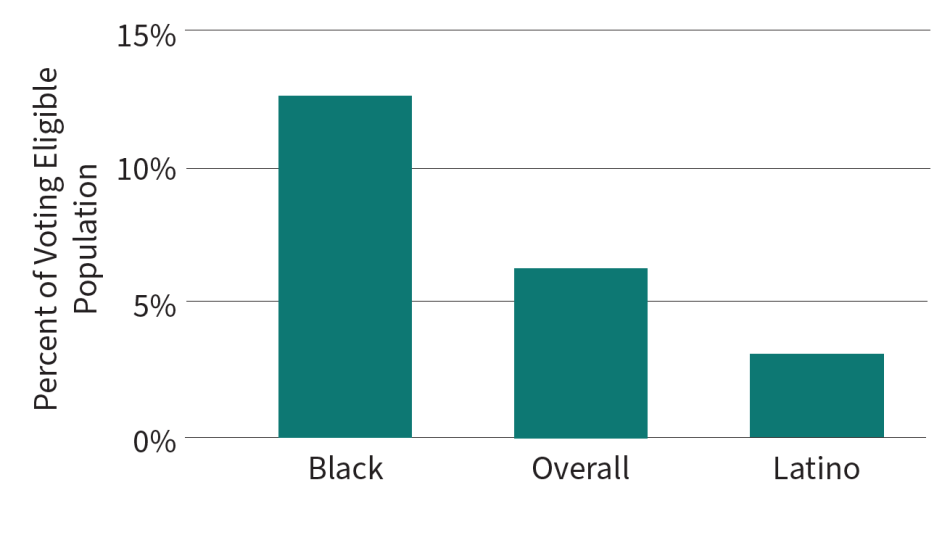

Not only are Florida’s felony disenfranchisement laws and policies an economic injustice, they are also a racial injustice. In 1980, 6% of voting eligible Black Floridians were disenfranchised.3 In 2024, this rate surpassed 12%. Voting eligible Black Floridians are disenfranchised at a rate over two and a half times that of non-Black Floridians. The disenfranchisement rate of Florida’s Latino population is nearly twice that of the Latino population nationwide – the seventh-highest rate of Latino disenfranchisement in the United States.4

Voter Exclusion Rates in Florida by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Source: Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

To ameliorate this economic and racial injustice and protect its democratic values, Florida lawmakers should extend voting rights to all citizens with felony convictions, regardless of their conviction offense, current incarceration or community supervision status and ability to pay legal financial obligations.

Racial Injustice in Florida’s Criminal Legal System Causes Disparities in Disenfranchisement

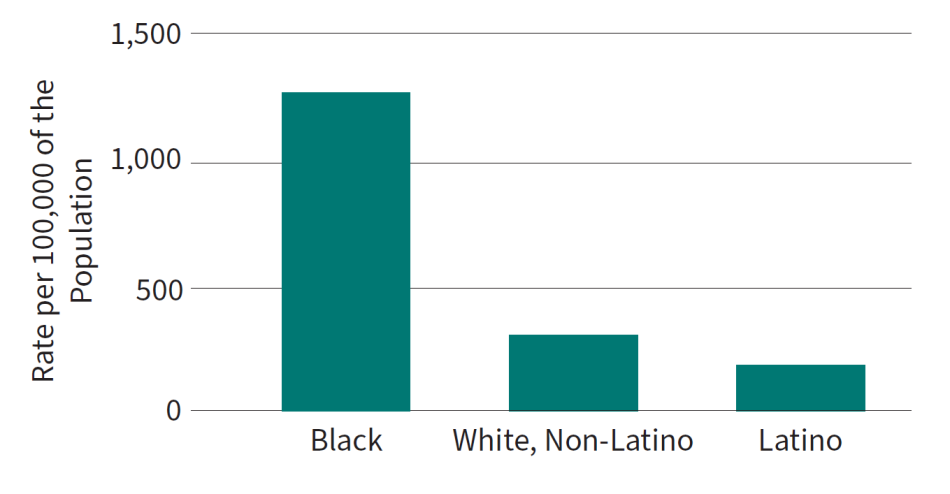

Felony disenfranchisement inflicts unequal weight on Black Floridians, largely due to disparities in the state’s criminal legal system. Despite comprising 15% of the total population in Florida, Black people make up almost 48% of those in prison.5

Imprisonment Rates in Florida by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Source: Office of Strategic Initiatives (2024). Annual Report, FY 23-24. Florida Department of Corrections; U.S. Census Bureau (2023). American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables – table B03002. U.S. Census Bureau.

Such disparities in incarceration go beyond differences in criminal offending and result from differential practices throughout Florida’s criminal legal system. These examples explain criminal justice practices that have differential effects on racial and ethnic groups:

- Black and Latino defendants facing felony charges in Jacksonville and Tampa were less likely to be diverted than their white counterparts, according to prosecutorial data analyzed from 2017 to 2019. The study, part of the Prosecutorial Performance Indicators project conducted by Florida International University (FIU) and Loyola University Chicago, found that racial disparities persisted even in comparable cases, such as first-time offenders charged with cannabis possession.6

- A 2023 study of drug changes in the Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency showed that Black and Latino individuals in Miami-Dade County face more severe charges than White non-Latino individuals, especially at arrest. The disparity persists through the later stages of filing and conviction with fewer reductions in charge severity for Black and Latino individuals, even after accounting for factors like criminal history and economic status—ultimately increasing the likelihood of imprisonment for people of color.7

- A 2012 study in the Quarterly Journal of Economics examining felony jury trials from 2000 to 2010 found that all-white jury pools in Florida convicted Black defendants 16% more often than white defendants.8

Florida should safeguard democratic rights and not allow a racially disparate criminal legal system to restrict voting rights.

Supporting Voting Rights Improves Public Safety

Research shows that an opportunity to participate in democracy has the potential to reduce one’s perceived status as an “outsider.” The act of voting can have a meaningful and sustaining positive influence on justice-impacted citizens by making them feel they belong to a community.9 Having a say and a stake in the life and well-being of your community is at the heart of our democracy.

Re-enfranchisement can facilitate successful re-entry and reduce recidivism. The University of Minnesota’s Christopher Uggen and New York University’s Jeff Manza find that among people with a prior arrest, there are “consistent differences between voters and non-voters in rates of subsequent arrest, incarceration, and self-reported criminal behavior.”10 Research also suggests having the right to vote immediately after incarceration matters for public safety. Individuals in states which continued to restrict the right to vote after incarceration were found to have a higher likelihood of experiencing a subsequent arrest compared to individuals in states who had their voting rights restored post-incarceration.11 Given re-enfranchisement misinformation and obstacles facing justice-impacted citizens upon re-entry into our communities, one path to bolster public safety and promote prosocial identities is to preserve voting rights during incarceration.

Allowing people to vote—including those incarcerated for a felony, under community supervision, or who have yet to pay in full associated fines and fees—supports successful reentry and strengthens civic identity. By ending disenfranchisement as a consequence of a felony conviction, Florida can improve public safety while also promoting reintegrative prosocial behaviors.

Florida Can Strengthen its Democracy by Restoring the Right to Vote

Almost 65% of Florida voters said “yes” to the 2018 ballot referendum – Amendment 4 – which restored justice-impacted Floridians voting rights after completing sentences for felony convictions and any associated probation or parole although it excluded restoration for persons convicted of murder or a felony sexual offense. The Florida legislature then circumvented the will of the people by passing Senate Bill 7066, requiring full payment of restitution, or any fines, fees, or costs resulting from conviction.12 This took away the right to vote of a large percentage of justice-impacted Floridians.

For Floridians with past felony convictions who are not eligible under Amendment 4, clemency is their primary pathway to restoration of voting rights. A 2018 study of the outcomes of the Board of Executive Clemency across several administrations found a dramatic decline in the number of people whose voting rights were restored through this route since 2011.13 While some prior governors restored rights for similar numbers of Black and white Floridians, racial disparity in voting rights restorations grew dramatically beginning in 2011. While Black Floridians comprised 44% of voting rights restorations between 1999 and 2011, they made up only 28% of restorations between 2011 and 2018.14

Racial injustice permeates not only Florida’s criminal legal system, but also its clemency decision-making process. Putting a price tag on voting and excluding justice-impacted people due to their conviction offense limits civic engagement, connection with community, and the construction of pro-social identities. Florida should ensure all of its citizens can participate in the democratic process, and respect the state’s constitutional provision that “all political power is inherent in the people.”15 Florida should advance both economic and racial justice by re-enfranchising its entire voting eligible population.

| 1. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Sebastian, T., Lang, D., & Short, C. E. (2020). Democracy, if you can afford it: How financial conditions are undermining the right to vote. UCLA Criminal Justice Law Review, 4(1), 79-116. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5m11662b; Slavinski, I., & Spencer-Suarez, K. (2021). The Price of Poverty: Policy Implications of the Unequal Effects of Monetary Sanctions on the Poor. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 37(1), 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986220971395 |

| 3. | Voting eligible adults are defined as individuals who are at least 18 years old and a U.S. citizen; R. Larson & C. Uggen, personal communication, October 10, 2022. |

| 4. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 5. | Office of Strategic Initiatives (2024). Annual Report, FY 23-24. Florida Department of Corrections; U.S. Census Bureau (2023). American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables – table B03002. U.S. Census Bureau. |

| 6. | Kutateladze, B. L., Dunlea, R. R., Pearson, M., Liu, L., Meldrum, & Stemen, D. (2021). Race and prosecutorial diversion: What we know and what can be done. https://prosecutorialperformanceindicators.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/FIU-Race-and-Prosecutorial-Diversion-D.pdf?eType=EmailBlastContent&eId=848ddac9-938d-41a6-94c9-d405b80d5c50 |

| 7. | Johnson, O., Omori, M., & Petersen, N. (2023). Racial-ethnic disparities in police and prosecutorial drug charging: analyzing organizational overlap in charging patterns at arrest, filing, and conviction. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 60(2), 255-299. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224278221120810 |

| 8. | Anwar, S., Bayer, P., & Hjalmarsson, R. (2012). The impact of jury race in criminal trials. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(2), 1017–1055. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjs014 |

| 9. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 10. | Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2004). Voting and subsequent crime and arrest: Evidence from a community sample. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 36(1), 193-216. |

| 11. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 12. | Brennan Center for Justice. (2022, August 10). Voting rights restoration efforts in Florida. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/voting-rights-restoration-efforts-florida |

| 13. | Ramadan, L., Stucka, M., & Washington, W. (2018, October 25). Florida felon voting rights: Here’s who got theirs back under Scott. The Palm Beach Post. https://www.palmbeachpost.com/story/news/politics/elections/2018/10/25/florida-felon-voting-rights-who-got-theirs-back-under-scott/5886930007/ |

| 14. | Ramadan, L., Stucka, M., & Washington, W. (2018, October 25). Florida felon voting rights: Here’s who got theirs back under Scott. The Palm Beach Post. https://www.palmbeachpost.com/story/news/politics/elections/2018/10/25/florida-felon-voting-rights-who-got-theirs-back-under-scott/5886930007/ |

| 15. | FL Const. Art. 1 § 1. |