Georgia Should Restore Voting Rights to Over 249,000 Citizens

Georgia’s rate of voter exclusion exceeds the national average – 3.25% of the state’s voting age population versus 1.7% nationally.

Related to: Voting Rights, State Advocacy

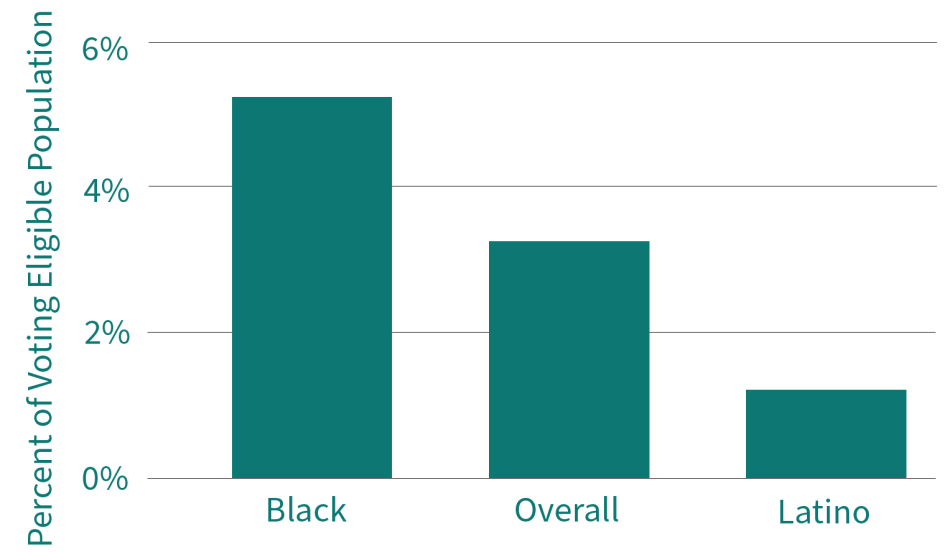

Georgia denies the right to vote to more than 249,000 of its citizens with a felony-level conviction. Georgia’s rate of voter exclusion exceeds the national average – 3.25% of the state’s voting age population versus 1.7% nationally. This ban from the ballot box falls heavily on people of color. Voting eligible Black Georgians are over two times as likely as non-Black Georgians to lose their right to vote due a felony-level conviction.1

Georgia denies the right to vote to all people in prison, on felony probation or parole and is thus more prohibitive than 24 states and Washington, DC.2 The law restricting voting by people with felony-level convictions undermines Georgia’s democracy and extends the racial injustice embedded in the criminal legal system to its electoral system. Lawmakers should extend voting rights to all citizens with felony-level convictions, including persons completing felony sentences in prisons or jails or completing their sentence in the community.

Voter Exclusion Rates in Georgia by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Source: Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R. & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked Out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

Most Disenfranchised Georgians Reside in the Community

Despite recent clarity provided by Georgia’s Secretary of State regarding restoration of voting rights after the payment of assessed fines and fees, Georgia’s disenfranchisement rate remains high due to strict voting laws and the share of residents placed under correctional control.3 Georgia’s community supervision population rate is the largest in the country.4 Reporting indicates that the average length of felony probation in Georgia is 6.3 years, nearly double the national average.5 Currently, over 190,000 Georgians are ineligible to vote because they are under felony probation or parole.6 Georgia’s high rate of community supervision occurs alongside its above-average imprisonment rate (435 per 100,000 residents)–higher than that of all of its neighboring states.7

Georgia’s Laws are Outdated and Confusing

Georgia’s felony disenfranchisement law dates back to 1877. During the state’s constitutional convention, officials added the wording, “no person who has been convicted of a felony involving moral turpitude may register, remain registered, or vote except upon completion of the sentence.”8 The phrase ‘moral turpitude’ has never been adequately defined by the state, and despite continued reference to the phrase in case law, neither state legislators nor the judicial branch have sought to establish a clear definition.9 In practice the phrase has included every crime classified as a felony.10

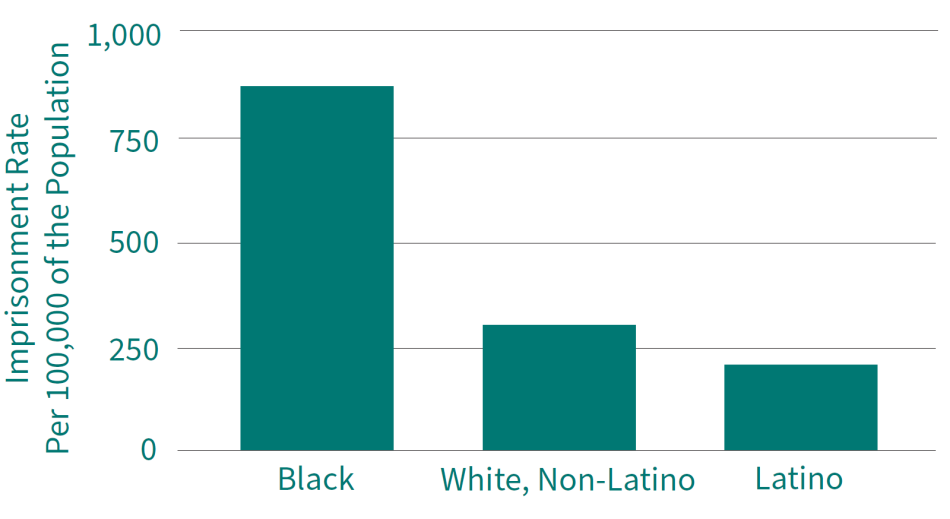

Racial Disparities in Criminal Justice Drive Disparities in Political Representation

Felony disenfranchisement bears unequal weight on communities of color in Georgia, largely due to disparities in the state’s criminal legal system. While 31% of Georgia’s population is Black, 61% of people in the state’s prisons are Black.11 Racial disparities are also evident in community supervision. More than half of Georgians on parole are Black.12

Imprisonment Rate in Georgia by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Source: Office of Information Technology (2025). Inmate Statistical Profile: All Active Inmates – December 2024. Georgia Department of Corrections. U.S. Census Bureau (2023). Hispanic or Latino origin by race. American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables, table B03002.

Supporting Voting Rights Improves Public Safety

Research shows that an opportunity to participate in democracy has the potential to reduce one’s perceived status as an “outsider.” The act of voting can have a meaningful and sustaining positive influence on justice-impacted citizens by making them feel they belong to a community.13 Having a say and a stake in the life and well-being of your community is at the heart of our democracy.

Re-enfranchisement can facilitate successful re-entry and reduce recidivism. The University of Minnesota’s Christopher Uggen and New York University’s Jeff Manza find that among people with a prior arrest, there are “consistent differences between voters and non-voters in rates of subsequent arrest, incarceration, and self-reported criminal behavior.”14 Research also suggests having the right to vote immediately after incarceration matters for public safety. Individuals in states which continued to restrict the right to vote after incarceration were found to have a higher likelihood of experiencing a subsequent arrest compared to individuals in states who had their voting rights restored post-incarceration.15 Given re-enfranchisement misinformation and obstacles facing justice-impacted citizens upon re-entry into our communities, one path to bolster public safety and promote prosocial identities is to preserve voting rights during incarceration.

Allowing people to vote, including persons completing felony sentences in prison or jail and in the community, prepares them for more successful reentry and bolsters a civic identity. By ending disenfranchisement as a consequence of incarceration, Georgia can improve public safety while also promoting reintegrative prosocial behaviors.

Georgia Can Protect Democracy By Ending Disenfranchisement

State lawmakers can build on growing support for protecting voting rights and promoting democracy by pursuing universal re-enfranchisement.16 Universal voting would increase fair and equal representation. Voting as an act of civic engagement ensures that political power reflects the communities of people in prison rather than the jurisdictions where they are incarcerated. Furthermore, addressing the barriers to restoring voting rights and supporting enhanced information sharing between people experiencing reentry can bolster participation in the political process for many formerly disenfranchised people.17

Everyone should maintain their right to vote. U.S. District Attorney for the Southern District of Georgia, David H. Estes, states that “Every citizen must be able to vote with-out interference or discrimination and to have that vote counted in a fair and free election.”18 Georgia should join Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC in ensuring all of its citizens can participate in the democratic process and ensure that, as written in the Georgia state constitution, all government originates “with the people” and “is founded upon their will only.”19 Georgia should advance racial justice by re-enfranchising its entire voting age population.

| 1. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked Out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project; Voting eligible adults are defined as individuals who are at least 18 years old and a U.S. citizen. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked Out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 3. | Niesse, M. (2020, September 17). Georgia election officials say ex-felons can vote while paying debts. Atlanta Journal-Constitution. https://www.ajc.com/politics/georgia-election-officials-say-ex-felons-can-vote-while-paying-debts/3YHUKB5MHFGP7POBNZFDXIWBTE/ |

| 4. | Georgia Department of Community Supervision (2025). Five fast facts on community supervision. Georgia Department of Community Supervision; Schrader, E. (2022, May 13). Shadow of Jim Crow: Georgia activists fight for voting rights for people with felony convictions. Southern Poverty Law Center. https://www.splcenter.org/news/2022/05/13/shadow-jim-crow-georgia-activists-fight-voting-rights-people-felony-convictions |

| 5. | Swartzenruber, A. & Bramlett, M. (2019). Fact sheet on felony disenfranchisement in Georgia. Reform Georgia; Georgia Justice Project. (2021, February 25). Probation reform bill unanimously passes Georgia Senate chamber. The Atlanta Voice. |

| 6. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked Out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 7. | Carson, A. (2024, October 15). Prisoners in 2022: Statistical tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 8. | ACLU Georgia. (2019). Felony disenfranchisement in Georgia. ACLU. |

| 9. | Nussbaum, K. (2020, October 26). “Moral turpitude” as defined by Chatham Elections Board to impact candidate Tony Riley. Savannah Now. |

| 10. | Holloway v. Holloway, 126 Ga. 459, 460 (1906). |

| 11. | U.S. Census Bureau (2023) Hispanic or Latino origin by race. American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables, table B03002. U.S. Census Bureau (2020). Quickfacts: Georgia. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/GA; Georgia Department of Corrections. (2022). Inmate statistical profile. https://gdc.ga.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/Profile_all_inmates_2022_10.pdf |

| 12. | Kaeble, D. (2024). Probation and parole in the United States, 2022. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 13. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 14. | Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2004). Voting and subsequent crime and arrest: Evidence from a community sample. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 36(1), 193-216. |

| 15. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 16. | Austin, D. (2020, November 2). These Georgians can’t vote on Tuesday, But they’re mobilizing by the thousands. Facing South. |

| 17. | Kramon, C. (2024, October 10). Advocates in Georgia face barriers getting people who were formerly incarcerated to vote. AP News. |

| 18. | Department of Justice, U.S. Attorney’s Office Southern District of Georgia. (2022, October 29). Election officers named for Southern District of Georgia’s effort to ensure voting integrity. https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdga/pr/election-officers-named-southern-district-georgia-s-effort-ensure-voting-integrity |

| 19. |