Kentucky Bars Over 158,300 Citizens from Voting

Despite a gubernatorial executive order in 2019 designed to ease the burden of lifetime disenfranchisement for Kentuckians with felony convictions, Kentucky still denies the right to vote to more people with a felony conviction than 40 other states.

Related to: Voting Rights, Racial Justice, State Advocacy

Despite a gubernatorial executive order in 2019 designed to ease the burden of lifetime disenfranchisement for Kentuckians with felony convictions, Kentucky still denies the right to vote to more people with a felony conviction than 40 other states.1 Over 158,300 Kentuckians are excluded from participation in our democracy, representing more than 4.5% of the state’s voting eligible population.2 Driving Kentucky’s high disenfranchisement rate is its ban on voting for over 60,000 people on felony probation or parole, and more than 71,000 people who have completed their sentence.

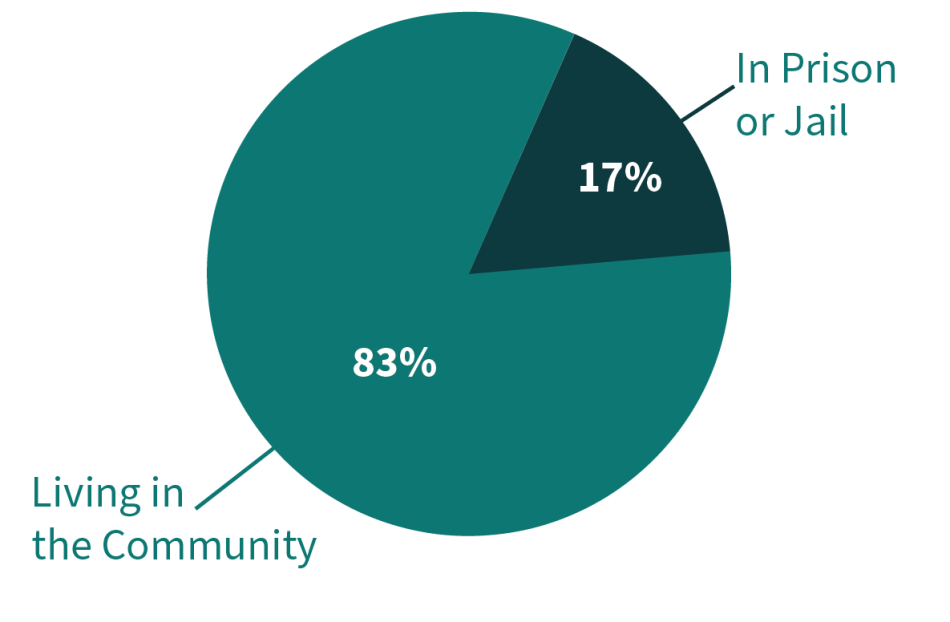

People Denied the Right to Vote Due to a Felony Conviction in Kentucky, 2024

Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

Kentucky’s voting ban results in stark racial injustices in ballot access. Kentucky has the country’s third highest rate of disenfranchisement for Black (11.67%) and Latino (4.35%) voting eligible Americans. Voting eligible Black Kentuckians are almost three times as likely as non-Black Kentuckians to lose their right to vote due to a felony-level conviction.3

To ameliorate this injustice and protect its democratic values, Kentucky lawmakers should extend voting rights to all people affected by the criminal legal system.

Racial Injustice Causes Disparities in Disenfranchisement

People of color are disproportionately disenfranchised in Kentucky because they are overrepresented in its criminal legal system. While Black Kentuckians make up only 8% of the population, they represent 21% of the correctional population and 17% of people disenfranchised due to being under felony probation or parole.4

Racial disparities in Kentucky’s criminal legal system go beyond differences in criminal offending. Examples of how criminal justice practices have differential effects on racial and ethnic groups include:

- Black people incarcerated in Kentucky are granted parole at lower rates than whites, according to Kentucky Parole Board chair Ladeidra Jones, exacerbating racial disparities in the criminal justice system.5

- Kentucky’s lack of racial data from which jury pools are drawn, in combination with prosecutorial bias, can lead to the repeated exclusion of Black citizens from juries.6 In his study on the impact of jury race on trials, economist Patrick Bayer found that Black defendants are significantly disadvantaged in trials with disproportionately small numbers of Black jurors.7

Racial bias and discrimination in the criminal legal system lock people of color out of the democratic process. Kentucky must re-enfranchise its citizens and invest in alternatives to incarceration that address racial injustice.

End Permanent Disenfranchisement

In December of 2019, Governor Andy Beshear issued an executive order to re-enfranchise over 170,000 people with past nonviolent convictions.8 However, voting rights advocates have criticized the order for excluding people with violent convictions who have completed their sentences, given that the severity of their crime had already been taken into account during their conviction and sentencing.

As evidenced by Kentucky’s history with executive reform, legislative action and constitutional change are crucial to making re-enfranchisement permanent. Several other states have made significant legislative changes to their lifetime felony disenfranchisement laws. Maryland repealed lifetime disenfranchisement in 2007, and restored voting rights to people on probation and parole in 2016. New Mexico has also abandoned lifetime disenfranchisement, restoring the right to vote to people upon completion of their sentence in 2001 and expanding the right to vote to people on felony probation and parole in 2023.9

Supporting Voting Rights Improves Public Safety

Research shows that an opportunity to participate in democracy has the potential to reduce one’s perceived status as an “outsider.” The act of voting can have a meaningful and sustaining positive influence on justice-impacted citizens by making them feel they belong to a community.10 Having a say and a stake in the life and well-being of your community is at the heart of our democracy.

Re-enfranchisement can facilitate successful re-entry and reduce recidivism. The University of Minnesota’s Christopher Uggen and New York University’s Jeff Manza find that among people with a prior arrest, there are “consistent differences between voters and non-voters in rates of subsequent arrest, incarceration, and self-reported criminal behavior.”11 Research also suggests having the right to vote immediately after incarceration matters for public safety. Individuals in states which continued to restrict the right to vote after incarceration were found to have a higher likelihood of experiencing a subsequent arrest compared to individuals in states who had their voting rights restored post-incarceration.12 Given re-enfranchisement misinformation and obstacles facing justice-impacted citizens upon re-entry into our communities, one path to bolster public safety and promote prosocial identities is to preserve voting rights during incarceration.

Allowing people to vote, including persons completing felony sentences in prisons or jails, under community supervision for a felony-level conviction, and those who have completed their sentences in full, prepares them for more successful reentry and bolsters a civic identity. By ending disenfranchisement as a consequence of incarceration, Kentucky can improve public safety while also promoting reintegrative prosocial behaviors.

Kentucky Can Preserve its Democracy by Restoring the Right to Vote

Excluding an entire population of people from exercising their right to vote undermines democracy. Fran Wagner, President of the League of Women Voters Kentucky says:

The most sacred principle of democracy is that individuals be allowed to impact how they are governed by voting. The right to vote grounds all other rights, empowering citizens to become participants in government rather than mere petitioners. It should not be denied to citizens who are trying to build new, productive lives.13

While Governor Beshear’s 2019 executive order was a significant step towards re-enfranchisement, advocates in Kentucky have expressed frustration at its limited attempts to alert its citizens of their rights.14 As of 2021, only 17% of Kentuckians with felony convictions have successfully submitted a voting application—approximately 31,000 people.15 Studies have found that voter turnout is greater in states that actively inform formerly incarcerated people of their rights, dispelling notions that people with convictions do not wish to engage in the political process.16

Felony disenfranchisement is the ultimate form of voter suppression, as it results in lifelong disenfranchisement that is onerous for Kentuckians to reverse. The restoration of voting rights has become a bipartisan cause in Kentucky, with members of law enforcement, religious leaders, elected officials and civil rights groups from both sides of the aisle supporting the cause.17 Across Kentucky, organizers are pushing for a constitutional amendment that would institute automatic re-enfranchisement for people who have completed their felony sentence.18 Universal voting promotes fair and equal representation and establishes trust between communities and their governments. Kentucky should continue its momentum of voting rights reform to re-enfranchise its entire voting age population.

| 1. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked Out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked Out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project; Voting eligible adults are defined as individuals who are at least 18 years old and a U.S. citizen. |

| 3. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked Out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 4. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked Out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project; Kentucky Department of Corrections (2024). Inmate Profiles: December 15, 2024. Kentucky Department of Corrections; U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). Hispanic or Latino Origin by Race. American Community Survey, ACS 5-Year Estimates Detailed Tables, Table B03002. |

| 5. | KY LRC Committee Meetings. (2021, August 18). Kentucky legislature 2021 live streams: Commission on race and access to opportunity 8/18. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N7rLtIC9o_o |

| 6. | Głowicki, M. (2016, March 16). Stevens ordered to stop dismissing jury panels. Courier Journal. https://www.courier-journal.com/get-access/?return=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.courier-journal.com%2Fstory%2Fnews%2Fcrime%2F2016%2F03%2F16%2Fstevens-ordered-stop-dismissing-jury-panels%2F81866880%2F |

| 7. | Anwar, S., Bayer, P., & Hjalmarsson, R. (2012). The impact of jury race on criminal trials. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(2), 1017-1055. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjs014 |

| 8. | Brennan Center for Justice. (2020, August 5). Voting rights restoration efforts in Kentucky: A summary of current felony disenfranchisement policies and legislative advocacy in Kentucky. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/voting-rights-restoration-efforts-kentucky |

| 9. | Chung, J. (2021). Voting rights in the era of mass incarceration: A primer. The Sentencing Project. |

| 10. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 11. | Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2004). Voting and subsequent crime and arrest: Evidence from a community sample. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 36(1), 193-216. |

| 12. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 13. | Wagner, F. (2022, November 3). Statement to the Interim Joint Judiciary Committee meeting. League of Women Voters of Kentucky. https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/CommitteeDocuments/8/20958/2022.11.3.%20Written%20STATEMENT%20to%20IJ%20Judiciacy%20Committee.pdf |

| 14. | Raymond, A. (2020, Sep 16). 170,000 Ex-felons can now vote in Kentucky. Who’s going to tell them? Spectrum News 1. https://spectrumnews1.com/ky/louisville/news/2020/09/16/registering-ex-felons-to-vote |

| 15. | Lewis, N., & Calderón, A. R. (2021, June 23). Millions of people with felonies can now vote. Most don’t know it. The Marshall Project. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2021/06/23/millions-of-people-with-felonies-can-now-vote-most-don-t-know-it |

| 16. | Lewis, N., & Calderón, A. R. (2021, June 23). Millions of people with felonies can now vote. Most don’t know it. The Marshall Project. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2021/06/23/millions-of-people-with-felonies-can-now-vote-most-don-t-know-it |

| 17. | Brennan Center for Justice. (2020, August 5). Voting rights restoration efforts in Kentucky: A summary of current felony disenfranchisement policies and legislative advocacy in Kentucky. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/voting-rights-restoration-efforts-kentucky |

| 18. | Lewis, N., & Calderón, A. R. (2021, June 23). Millions of people with felonies can now vote. Most don’t know it. The Marshall Project. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2021/06/23/millions-of-people-with-felonies-can-now-vote-most-don-t-know-it |