Life in Prison Without Parole in Louisiana

Louisiana’s share of people serving life without the possibility of parole (LWOP) ranks highest per capita nationally and across the globe.

Related to: Sentencing Reform, Incarceration, Racial Justice

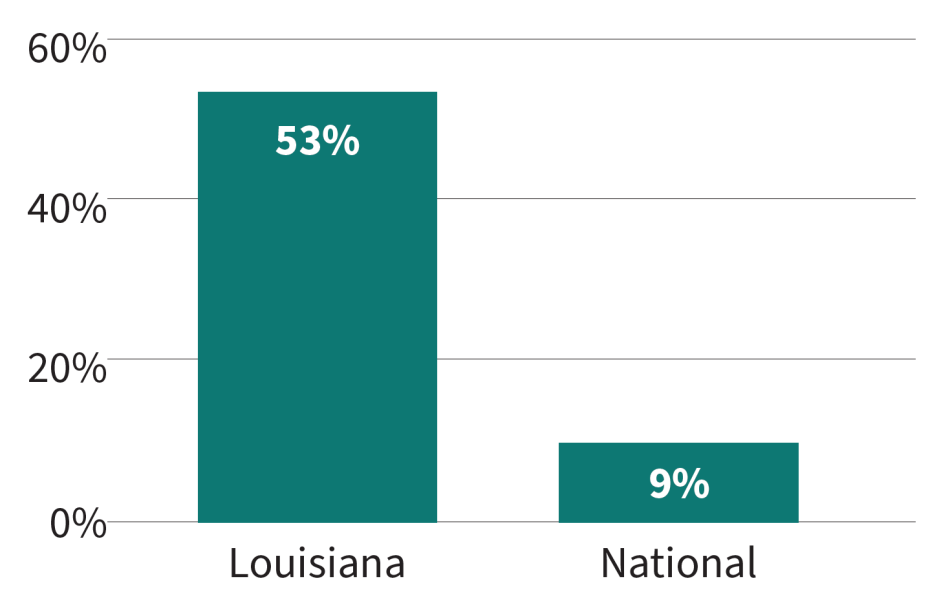

Louisiana’s share of people serving life without parole (LWOP) ranks highest per capita nationally and in the world. More than 4,000 Louisianans are serving sentences of life without the possibility of parole, amounting to 15% of this state’s prison population.1 Between 1995 and 2020, the state added an average of 110 people each year to its total count of life-sentenced individuals.2

A major driver behind the large share of people serving LWOP is the state’s automatic imposition of this sentence after conviction for second degree murder,3 making it one of only two states to impose LWOP in such instances.4 Louisiana’s second degree murder statute includes felony murder and drug induced homicide offenses; these cases often include instances where the charged individual was not the direct perpetrator of the killing, nor intended to commit it, though they participated in an underlying felony related to the victim’s death.5 It is important to note that felony murder laws such as that in Louisiana are not associated with a significant reduction in felonies nor have they lowered the number of felonies that become deadly.6 These crime types are infrequently subject to LWOP sentences elsewhere, much less mandatorily imposed.7 But in Louisiana, LWOP in response to second degree murder is both authorized and mandatory.

As shown in Figure 1, more than half of those serving LWOP have been convicted of second degree murder. Laws that hold all people present during a homicide equally responsible despite varying levels of participation violate basic tenets of proportional sentencing that undergird the American criminal legal system. Louisiana’s LWOP sentences embody the worst of these laws.

Figure 1. Proportion of People Serving LWOP for Second Degree Murder, 2020

Source: Nellis, A. (2021). No end in sight: America’s enduring reliance on life imprisonment. The Sentencing Project.

Age and Crime

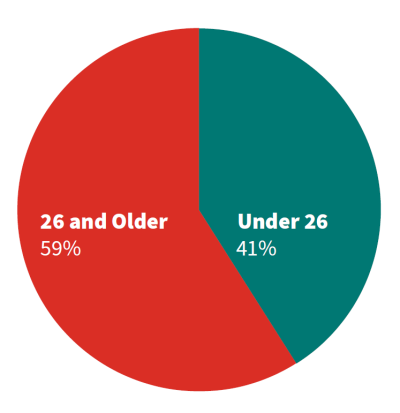

The state’s heavy use of life sentences with no chance for review on young people and emerging adults is another feature of the statute’s especially draconian nature. Four in 10 people sentenced to LWOP in Louisiana were 25 or younger at the time of their sentence.8 It is a criminological reality that the likelihood of committing crime increases through one’s teenage years and early twenties, falling dramatically as people approach adulthood. Researchers use the term “aging out” to describe this phenomenon, which occurs alongside maturity and brain development.9 Ages 18 to 25 mark a unique stage of life between childhood and adulthood which is recognized within the fields of neuroscience, sociology, and psychology.10 Adolescent development research finds important differences between youth and older adolescents up to their mid-twenties when compared to adults in terms of risk taking, accurate calculation of consequences, and influence by negative peer pressure.11 Though young age does not excuse criminal behavior entirely, and consequences are an important feature of behavior correction, a second look at individuals once they are fully developed and beyond their crime-prone years would allow decision makers to identify those who are no longer a risk to public safety.

Figure 2. Age at Sentencing Among People Sentenced to LWOP in Louisiana between 1990 and 2018

Source: Louisiana Department of Corrections data provided to The Sentencing Project.

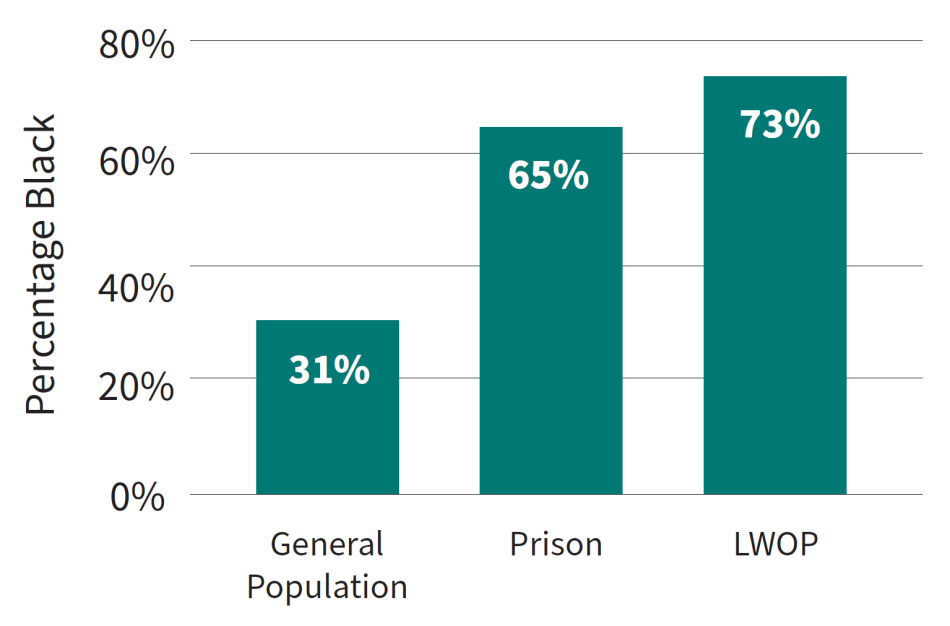

Racial Disparities

While Black Louisianas are over-represented in the state’s prisons, this disparity is most severe for those sentenced to LWOP, particularly the young. Two thirds of people in Louisiana prisons are Black, but among people sentenced to LWOP three quarters are Black. A staggering 81% of those who were 26 and younger when convicted of second degree murder are Black.12

Figure 3. Black Louisianans as a Percentage of the State’s General Population, Prison Population, and Persons Sentenced to LWOP

Sources: Carsen, A. E. (2022). Prisoners in 2021. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Nellis, A. (2021). Individuals serving life without parole. [unpublished raw data]. The Sentencing Project.; United States Census Bureau (2023). Quick facts: Louisiana. Accessed December 15, 2023.

Time Served

More than half of Louisianans serving LWOP have been incarcerated for at least 20 years, including 200 men and women who have been in prison for at least 40 years. Statistically, these individuals are the least likely to reoffend, having been incarcerated for a substantial period of time and being over 50 years of age.13

Conclusion

Life sentences with no chance for review or release stand at odds with the well-documented and predictable patterns in criminal conduct. People who have committed crime, even violent crime, have relatively short criminal careers and tend to commit crime in their youth and young adulthood.14 Excessively long prison sentences produce diminishing returns on public safety and rob struggling communities with necessary resources to fend off violence in the first place. Statutes that require lifelong imprisonment despite varying levels of involvement and intent are especially cruel and misguided.

Legislative proposals that follow the science with regard to criminal sentences secure a functional corrections system that is responsive to community needs for both accountability and crime control. In supporting the end of mandatory LWOP sentencing for felony murder, Louisiana lawmakers will increase proportionality and judicial discretion, and allow those who are rehabilitated to reenter society when they are fit to do so. A “safety valve” mechanism in the statute would allow, but not require judges to apply downward departures in certain scenarios.

| 1. | Demographic Dashboard – Louisiana Department of Public Safety & Corrections. Data accessed on December 26, 2023. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Louisiana Department of Corrections (2021). Sentencing data provided to The Sentencing Project in response to a public records request. |

| 3. | In Louisiana, individuals can be charged with first degree murder if they commit an intentional homicide with the presence of one of several aggravating factors, such as they are engaged in an enumerated serious felony or they intentionally target a correctional officer. Individuals who commit an intentional homicide, as well as individuals accused of felony murder or drug delivery resulting in death, can otherwise be charged with second degree murder. |

| 4. | Pennsylvania also requires LWOP for second degree murder convictions. All states with LWOP statutes allow the punishment for first degree murder and 29 states and the federal government require it. See Ghandnoosh, N., Stammen, E. & Budaci, C. (2022). Felony murder: An on ramp for extreme sentencing. The Sentencing Project. |

| 5. | Ghandnoosh, N., Stammen, E. & Budaci, C. (2022). Felony murder: An on ramp for extreme sentencing. The Sentencing Project. |

| 6. | Ghandnoosh, N. (2022). Felony murder: An on-ramp for extreme sentencing.The Sentencing Project. |

| 7. | Ghandnoosh, N., Stammen, E. & Budaci, C. (2022). Felony murder: An on ramp for extreme sentencing. The Sentencing Project. |

| 8. | Nellis, A. (2023). Left to die: Emerging adults under 25 sentenced to LWOP. The Sentencing Project. |

| 9. | Laub, J. & Sampson, R. (2003). Shared beginnings, divergent lives: Delinquent boys to age 70. Harvard University Press; Sweeten G., Piquero A. R., & Steinberg L. (2013). Age and the explanation of crime, revisited. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 921–923. |

| 10. | Bigler, E. (2021). Charting brain development in graphs, diagrams, and figures from childhood, adolescence, to early adulthood: Neuroimaging implications for neuropsychology. Journal of Pediatric Neuropsychology, (7)1-2, 27–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40817-021-00099-6; Casey, B. J., Simmons, C., Somerville, L., & Baskin-Sommers, A. (2022). Making the sentencing case: Psychological and neuroscientific evidence for expanding the age of youthful offenders. Annual Review of Criminology, 5(1), 321–343. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-030920-113250. |

| 11. | Steinberg, L. & Icenogle, G. (2019). Using developmental science to distinguish adolescents and adults under the law. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology (1)1, 21-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-devpsych-121318-085105. |

| 12. | Nellis, A. (2023). Left to die: Emerging adults under 25 sentenced to LWOP. The Sentencing Project. |

| 13. | Nellis, A. (2022). Nothing but time: Elderly Americans serving life without parole. The Sentencing Project. |

| 14. | Cauffman, E. & Steinberg, L. (2000). (Im)maturity of judgment in adolescence: Why adolescents may be less culpable than adults. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 18(6), 741-760; Scott, E., & Steinberg, L. (2010). Rethinking juvenile justice. Harvard University Press; Steinberg, L. & Scott, E. (2003). Less guilty by reason of adolescence: Developmental immaturity, diminished responsibility, and the juvenile death penalty. American Psychologist, 58(12), 1009-1018. |