Massachusetts Should Restore Voting Rights to Over 7,300 Citizens

Massachusetts should strengthen its democracy and advance racial justice by restoring the vote to its entire voting-age population.

Related to: Voting Rights, State Advocacy

More than 7,300 Massachusetts citizens are banned from voting in elections due to incarceration for a felony conviction.1 In 2000, Massachusetts disenfranchised this entire population through a constitutional amendment stripping its citizens of their political voice.2 People of color in particular are more likely to be prohibited from voting because of the stark racial disparities in the Massachusetts criminal legal system.

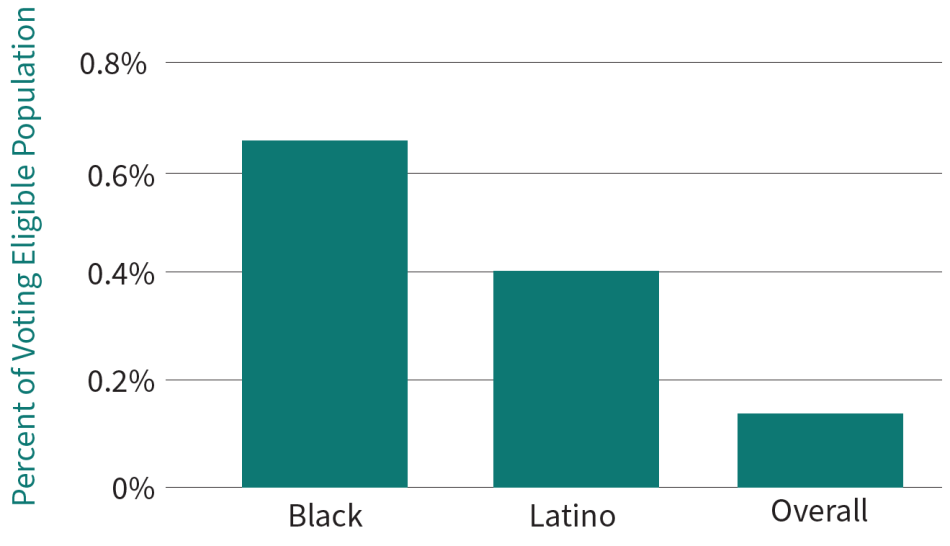

Voter Exclusion Rates in Massachusetts by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

Massachusetts’s voting ban results in stark racial injustices in ballot access. Voting-eligible Black residents are almost six times as likely as non-Black residents to lose their right to vote due to incarceration for a felony conviction.3 The voter exclusion rate of Massachusetts’s voting-eligible Latino population is over three times that of the non-Latino voting-eligible population.4

The law restricting voting for people with felony convictions undermines Massachusetts’s democracy and extends the racial injustice embedded in the criminal legal system to its electoral system. To ameliorate this racial injustice and protect its democratic values, Massachusetts should follow the lead of Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC, and extend voting rights to all citizens, including persons completing their felony-level sentence in prison or jail.

Expanding Voting Rights in Massachusetts is a Racial Justice Issue

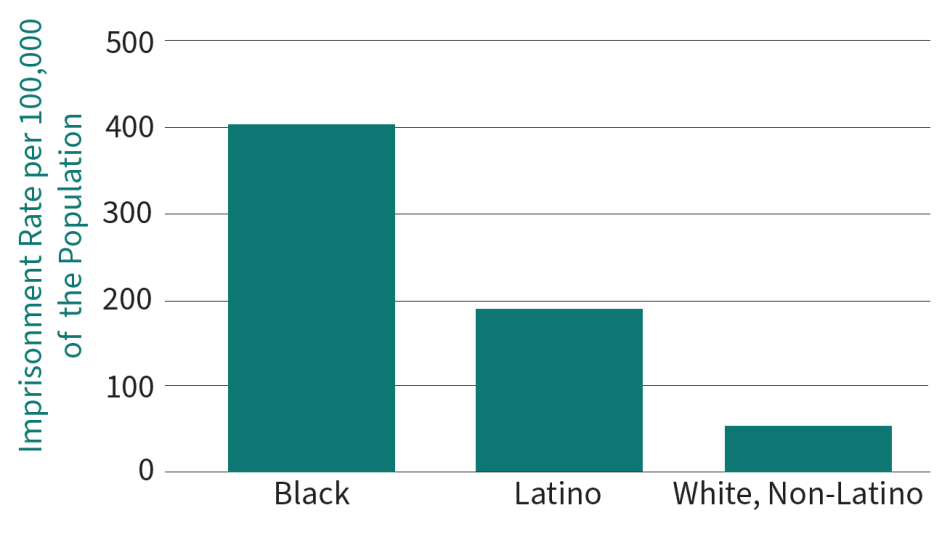

Voter exclusion is particularly acute for Black and Latino residents of Massachusetts due to their disproportionate incarceration. Less than 7% of the state’s population is Black, but 30% of the prison population is Black. Similarly, less than 13% of the state’s population is Latino, but Latino people make up 28% of the prison population.5

Imprisonment Rate in Massachusetts by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Massachusetts Department of Correction. (2024). Population data dashboard: Race and ethnicity [Data dashboard]; U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). Hispanic or Latino origin by race, American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables, table B03002.

Such disparities in incarceration go beyond differences in criminal offending and result from differential treatment throughout Massachusetts’s criminal legal system.

The following examples illustrate the disparate effects of these practices on people of color in Massachusetts:

- Policing: Researchers analyzed Field Interrogation and Observation (FIO) reports (more commonly known as “Stop and Frisk”) between 2007 and 2010 from the Boston Police Department. While the amount of serious crime strongly predicted FIO activity, further analysis showed that as the percentage of Black and Latino residents in a neighborhood increased relative to the percentage of white residents, the amount of FIO reports made by Boston police increased as well. The racial disparities persisted even after controlling for total crime incidents per month, police activity, and other characteristics such as concentrated disadvantage.6

- Prosecutorial Discretion: Black and Latino residents in Massachusetts face racially disparate treatment in initial charging decisions, leading to longer sentences on average compared to white residents. According to a report by the Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School, Black and Latino defendants were more likely to have their cases tried in Superior Court than white defendants in similar situations. This disparity matters because only Superior Courts can impose sentences longer than two and a half years in state prison. Between 2014 and 2016, these charging differences also meant that Black and Latino individuals were less likely than similarly situated whites to have their cases resolved in ways that did not lead to incarceration, especially in drug and gun cases.

- Sentencing: An analysis of Massachusetts Department of Corrections data by the Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School found that Black and Latino individuals charged with weapon or drug offenses were more likely to be incarcerated and received longer prison sentences than white individuals even when case severity and criminal history were taken into account. For example, Black individuals with a weapon offense as their most serious conviction received a sentence 125 days longer on average than white individuals with a weapon offense as their most serious conviction.7

Racial disparity in the criminal legal system dilutes the political voice of people of color in Massachusetts. Massachusetts should safeguard democratic rights and not allow a racially disparate criminal legal system to restrict voting rights.

Supporting Voting Rights Improves Public Safety

Research shows that an opportunity to participate in democracy has the potential to reduce one’s perceived status as an “outsider.” The act of voting can have a meaningful and sustaining positive influence on justice-impacted citizens by making them feel they belong to a community.8 Having a say and a stake in the life and well-being of your community is at the heart of our democracy.

Re-enfranchisement can facilitate successful re-entry and reduce recidivism. The University of Minnesota’s Christopher Uggen and New York University’s Jeff Manza find that among people with a prior arrest, there are “consistent differences between voters and non-voters in rates of subsequent arrest, incarceration, and self-reported criminal behavior.”9 Research also suggests having the right to vote immediately after incarceration matters for public safety. Individuals in states which continued to restrict the right to vote after incarceration were found to have a higher likelihood of experiencing a subsequent arrest compared to individuals in states who had their voting rights restored post-incarceration.10 Given re-enfranchisement misinformation and obstacles facing justice-impacted citizens upon re-entry into our communities, one path to bolster public safety and promote prosocial identities is to preserve voting rights during incarceration.

Allowing people to vote, including persons completing felony sentences in prisons or jails, prepares them for more successful reentry and bolsters a civic identity. By ending disenfranchisement, as a consequence of incarceration, Massachusetts can improve public safety while promoting reintegrative prosocial behaviors.

Massachusetts Can Strengthen its Democracy by Restoring the Right to Vote

Since 1997, 26 states and the District of Columbia have expanded voting rights to people living with felony convictions. As a result, over 2 million Americans have regained the right to vote.11 Massachusetts stands as an outlier. In the late 1990s, incarcerated individuals in one of the state prisons established a Political Action Committee (PAC) to track elected officials’ positions on prison reform and encourage electoral participation among incarcerated voters and their families. Governor Paul Cellucci then banned the Massachusetts Prisoners Association PAC by executive order and proposed a constitutional amendment to disenfranchise voters sentenced to Massachusetts prisons.12

Massachusetts’s constitutional amendment in 2000 severed an entire population’s ability to vote in local and state elections, because they were incarcerated for a felony conviction. In 2001, Massachusetts continued to move in the wrong direction by further restricting voting rights – prohibiting people incarcerated for a felony from voting in federal elections.13 However, in 2023, lawmakers introduced numerous proposals to restore the voting rights of people incarcerated for a felony conviction.14 Such proposals should become law.

Excluding people from the right to vote due to felony convictions runs counter to the Massachusetts state constitution, which emphasizes that all power resides “originally in the people,” and all government authorities are “at all times accountable to them.”15 Massachusetts should strengthen its democracy and advance racial justice by restoring the vote to its entire voting eligible population.

| 1. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | |

| 3. | Voting eligible adults are defined as individuals who are at least 18 years old and a U.S. citizen. |

| 4. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 5. | Massachusetts Department of Correction. (2024). January 1st snapshot dashboard – January 1st, 2024, Massachusetts Department of Correction; U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). Hispanic or Latino origin by race, American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables, table B03002. |

| 6. | Fagan, J., Braga, A. A., Brunson, R. K., & Pattavina, A. (2015). An analysis of race and ethnicity patterns in Boston police department field interrogation, observation, frisk, and/or search reports. Boston Police Department & ACLU of Massachusetts. |

| 7. | Bishop, E. T., Hopkins, B., Obiofuma, C., & Owusu, F. (2020). Racial disparities in the Massachusetts criminal system. Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School. |

| 8. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 9. | Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2004). Voting and subsequent crime and arrest: Evidence from a community sample. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 36(1), 193-216. |

| 10. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 11. | Porter, N., & McLeod, M. (2023). Expanding the vote: State felony disenfranchisement reform, 1997-2023. The Sentencing Project. |

| 12. | Prison Legal News (2000, October 15). Massachusetts prisoners political action committee floundering. Prison Legal News. |

| 13. | Ballots Over Bars (2019, March 10). Timeline of Massachusetts incarcerated voting rights. Emancipation Initiative. |

| 14. | Drysdale, S. (2023, April 28). Bill that would restore prison voting rights in Mass. advances out of election laws committee. State House News Service. |

| 15. |