New Mexico Should Restore Voting Rights to Over 5,300 Citizens

New Mexico denies the right to vote to over 5,300 citizens who are serving a sentence in prison or jail due to a felony-level conviction.

Related to: Voting Rights, Racial Justice, State Advocacy

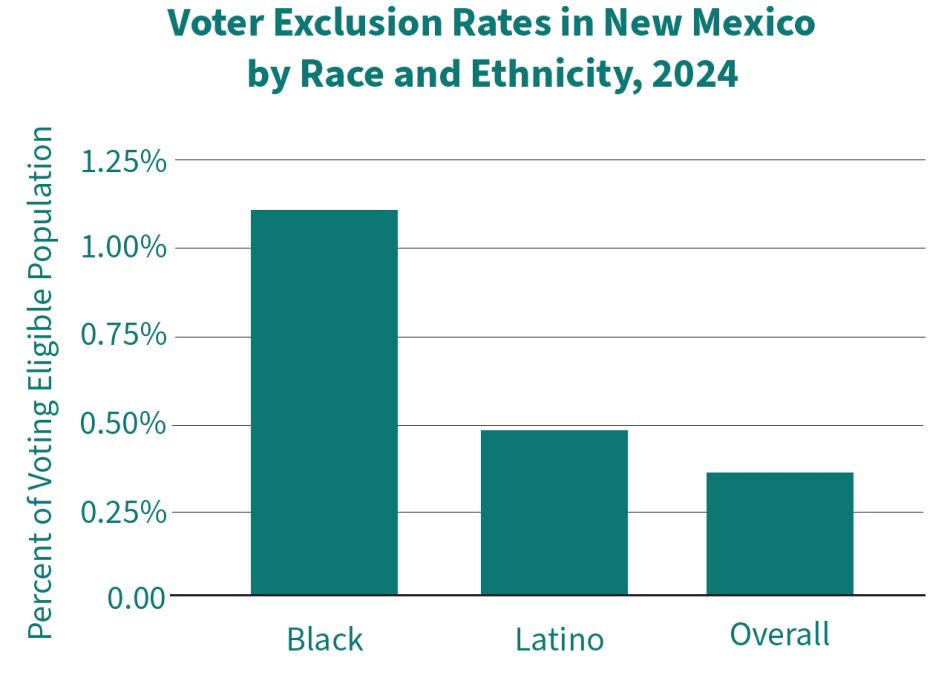

New Mexico denies the right to vote to over 5,300 citizens who are serving a sentence in prison or jail due to a felony-level conviction.1 This voter exclusion falls heavily on people of color. Voting eligible Black New Mexicans are over three times as likely as non-Black New Mexicans to lose their right to vote due to incarceration for a felony conviction. Latino New Mexicans are almost twice as likely as non-Latino New Mexicans to lose their right to vote due to incarceration for a felony conviction.2

The law restricting voting by people with felony convictions undermines New Mexico’s democracy and extends the racial injustice embedded in the criminal legal system to its electoral system. Lawmakers should extend voting rights to all citizens with felony-level convictions, including persons completing felony sentences in prisons or jails.

Voter Exclusion Rates in New Mexico by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked Out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

Expanding Voting Rights in New Mexico is a Racial Justice Issue

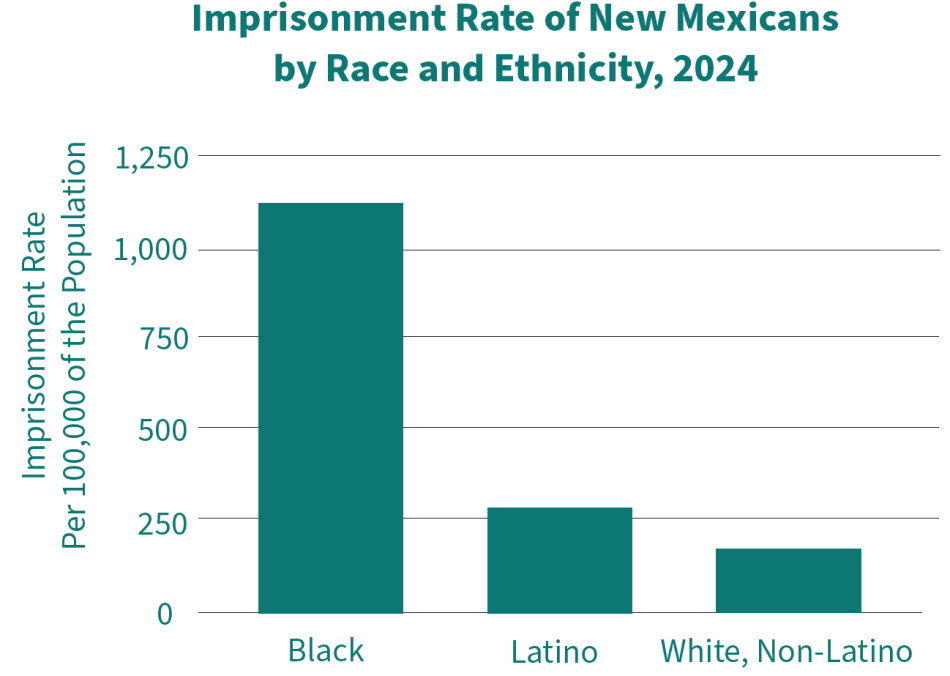

Voter exclusion bears unequal weight on communities of color in New Mexico, largely due to disparities in the state’s criminal legal system.3 While 2% of the state’s population is Black, 8% of the prison population is Black. Furthermore, Black New Mexicans are more than six times as likely as white residents to be in prison.4 Latino New Mexicans are also disproportionately incarcerated – over 1.5 times as likely to be in prison compared to white residents.

Imprisonment Rate of New Mexicans by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

McManaman, G. & Shane, N. (2025). Profile of New Mexico prison population FY24. New Mexico Sentencing Commission; U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). Hispanic or Latino origin by race. American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables, table B03002.

Such disparities in incarceration go beyond differences in criminal offending and result from differential practices throughout New Mexico’s criminal legal system. The following examples help explain criminal justice practices that have differential effects on racial and ethnic groups:

- The Council of State Governments Justice Center found that in 2022, Black New Mexicans were almost twice as likely to be arrested compared to white New Mexicans. They also found racial disparities in the arrest rates for Native American New Mexicans who were 1.4 times as likely to be arrested compared to white New Mexicans.5

- Three former police officers were whistleblowers in a civil lawsuit that alleged their former police department was targeting neighborhoods of color. Data analyzed by an expert witness showed that the police department in the city of Hobbs, New Mexico disproportionately stopped Black residents in pedestrian stops. Using Hobbs police department data, US Census data, and GIS mapping, “the south end of Hobbs, where minorities comprise more than 80% of the population, experienced pedestrian stops over the 2016 to 2018 period at a disproportionate rate compared to the remainder of Hobbs.”6

- The American Civil Liberties Union of New Mexico, the Drug Policy Alliance, New Mexico Voices for Children, and Young Women United analyzed a year’s worth of arrest and booking information from 2015 in Bernalillo County, New Mexico.7 The share of Latino and Black men and Latino, Black, and Indigenous women who were booked for drug violations were higher than their share in the total population. The share of white New Mexican men and women booked were lower than their share in the population.

Notably, Native Americans make up 8.5% of New Mexico’s population and 11% of its prison population.8 While no official felony disenfranchisement estimates are available for Native Americans, their representation in New Mexico’s population and criminal legal system indicates they too are heavily impacted by felony disenfranchisement laws and policies.9

New Mexico should safeguard democratic rights and not allow a racially disparate criminal legal system to restrict voting rights.

Supporting Voting Rights Improves Public Safety

Research shows that an opportunity to participate in democracy has the potential to reduce one’s perceived status as an “outsider.” The act of voting can have a meaningful and sustaining positive influence on justice-impacted citizens by making them feel they belong to a community.10 Having a say and a stake in the life and well-being of your community is at the heart of our democracy.

Re-enfranchisement can facilitate successful re-entry and reduce recidivism. The University of Minnesota’s Christopher Uggen and New York University’s Jeff Manza find that among people with a prior arrest, there are “consistent differences between voters and non-voters in rates of subsequent arrest, incarceration, and self-reported criminal behavior.”11 Research also suggests having the right to vote immediately after incarceration matters for public safety. Individuals in states which continued to restrict the right to vote after incarceration were found to have a higher likelihood of experiencing a subsequent arrest compared to individuals in states who had their voting rights restored post-incarceration.12 Given re-enfranchisement misinformation and obstacles facing justice-impacted citizens upon re-entry into our communities, one path to bolster public safety and promote prosocial identities is to preserve voting rights during incarceration.

Allowing people to vote, including persons completing felony sentences in prison or jail, prepares them for more successful reentry and bolsters a civic identity. By ending disenfranchisement as a consequence of incarceration, New Mexico can improve public safety while also promoting reintegrative prosocial behaviors.

Removing Barriers to Restore New Mexicans Voting Rights

The landmark New Mexico Voting Rights Act (2023) is a welcome step towards eliminating voter exclusion and enhancing the right to vote for thousands of New Mexicans affected by the carceral system.13 However, advocates in New Mexico have raised concerns around the implementation of the 2023 Act. Recent campaigns have sought to address unnecessary barriers and burdens created in the local and state-wide administration of voter registration, including the failure of the New Mexico Department of Corrections to provide accurate data to the Secretary of State on people who are no longer in prison or jails.14 Legal action in the case of Millions of Prisoners New Mexico v. Toulouse Oliver sought to challenge in-person registration requirements and misleading denial letters sent to formerly incarcerated people indicating that they are ineligible to vote.15 Although Millions of Prisoners won the lawsuit, with the judge ordering the Secretary of State to provide a list to each county clerk of people whose voter eligibility has been restored,16 more steps are essential to enhance access to the right to vote for formerly incarcerated individuals. This could include enhanced public efforts to ensure people are able to register to vote in a timely and safe manner.

People leaving carceral settings in New Mexico experience complex issues, including substance use, mental health challenges, or access to safe and secure housing.17 Because of this reality, more secure and accessible services to facilitate ease of voter registration is critical to ensuring formerly incarcerated people in New Mexico have the opportunity to register and vote.

New Mexico Can Strengthen its Democracy by Restoring the Right to Vote

Since 1997, 26 states and the District of Columbia have expanded voting rights to people with felony convictions resulting in over 2 million Americans having regained the right to vote.18 While New Mexico’s Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham, by signing the New Mexico Voting Rights Act in 2023, re-enfranchised over 11,000 New Mexicans completing felony probation or parole, over 5,300 New Mexicans remain banned from the ballot box. Efforts to support voting rights restoration should continue.19 This includes passing further legislation to restore voting rights to New Mexicans who are serving a sentence for a felony-level conviction in prisons or jails.

New Mexico should join Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC in ensuring all of their citizens can participate in our democratic process. Failing to do so would be an indictment against New Mexico’s own state Constitution, in which it is declared that “all political power is vested in and derived from the people,” and “all government…is instituted solely for their good.”20 The state government should be reflective of the interests and lives of all New Mexicans, and every person who is eligible to vote, should be able to do so and ensure their government represents them.

New Mexico should strengthen its democracy and advance racial justice by re-enfranchising its entire voting-eligible population.

| 1. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked Out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked Out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project; Voting eligible adults are defined as individuals who are at least 18 years old and a U.S. citizen. |

| 3. | McManaman, G. & Shane, N. (2025). Profile of New Mexico prison population FY24. New Mexico Sentencing Commission; U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). Hispanic or Latino origin by race. American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables, table B03002 |

| 4. | McManaman, G. & Shane, N. (2025). Profile of New Mexico prison population FY24. New Mexico Sentencing Commission; U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). Hispanic or Latino origin by race. American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables, table B03002 |

| 5. | Herman, M., Tallaksen, A., Moore, M., & Dardeau, M. (2023). New Mexico criminal justice data snapshot. Justice Reinvestment Initiative. |

| 6. | Associated Press. (2021, July 3). Hobbs settles e-cops suit over race-based enforcement. Albuquerque Journal. https://www.abqjournal.com/2406146/hobbs-settles-ex-officers-suit-over-race-based-enforcement.html?paperboy=loggedin630am; Cooper, W. S. (2019). Declaration of William S. Cooper. Civil Action NO.: 2:17-CV-01011-WJ-GBW. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/6788640-Hobbs-Plaintiff-Demographer-Report.html |

| 7. | American Civil Liberties Union of New Mexico, the Drug Policy Alliance, New Mexico Voices for Children, & Young Women United. 2017. Racial and ethnic bias in New Mexico drug law enforcement. https://www.nmvoices.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/DPA-report-corrected-web.pdf |

| 8. | McManaman, G. & Shane, N. (2025). Profile of New Mexico prison population FY24. New Mexico Sentencing Commission; U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). Hispanic or Latino origin by race. American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables, table B03002. |

| 9. | New Mexico also does not collect LGBTQIA+ data; therefore, there is no way to know how many LGBTQIA+ New Mexican citizens are disenfranchised due to a felony conviction. |

| 10. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 11. | Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2004). Voting and subsequent crime and arrest: Evidence from a community sample. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 36(1), 193-216. |

| 12. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 13. | New Mexico Legis., HB-4, Reg. Sess. 2023 (2023). https://www.nmlegis.gov/Sessions/23%20Regular/final/HB0004.pdf |

| 14. | Campaign Legal Center (2024). Ensuring fair voter registration practices in New Mexico (Millions for Prisoners New Mexico v. Toulouse Oliver. Campaign Legal Center; Gill, L. (2024, October 29). “A year of frustration”: How New Mexico kept denying people voting rights despite reform. Bolts. |

| 15. | Campaign Legal Center (2024). Ensuring fair voter registration practices in New Mexico (Millions for Prisoners New Mexico v. Toulouse Oliver. Campaign Legal Center. |

| 16. | Corey Howard (2024, October 9). Judge orders Secretary of State to restore felons’ voter registration rights. KOAT7. |

| 17. | New Mexico State Library (2025). Library resources for people who have experienced incarceration. New Mexico State Library. |

| 18. | Porter, N. & McLeod, M. (2023). Expanding the vote: State felony disenfranchisement reform, 1997-2023. The Sentencing Project. |

| 19. | Fisher, A. (2022, January 27). Secretary of State talks details of NM’s Voting Rights Act: Proposal is meant ot expand voting rights access. Does it go far enough? Source NM. https://sourcenm.com/2022/01/27/secretary-of-state-talks-details-of-nms-voting-rights-act/; McDevitt, M. (2021, February 6). Taking back their voice: Bill aims to lower barriers to restoring felons’ voting rights. Las Cruces Sun News. https://www.lcsun-news.com/story/news/2021/02/06/new-mexico-bill-expanding-felon-voting-rights-clears-house-committee/4391644001/ |

| 20. | N.M. Const. Bill of Rights, § 2 – Popular sovereignty. https://www.sos.nm.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/NM_Constitution_-2025-for-SOS.pdf |