New York Should Restore Voting Rights to Over 33,000 Citizens

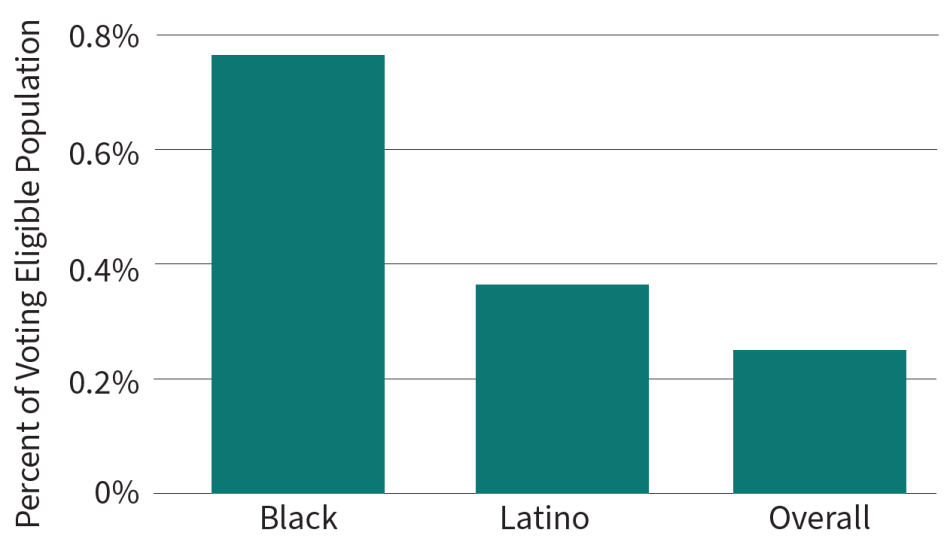

Black New Yorkers are excluded from voting due to a felony conviction at over five times the rate of non-Black New Yorkers. For Latino New Yorkers, their voter exclusion rate is almost twice that of non-Latino New Yorkers.

Related to: Voting Rights, Racial Justice, State Advocacy

New York denies the right to vote to over 33,000 citizens because they are completing felony-level sentences in prisons or jails across the state.1 This ban from the voting box falls heavily on people of color. Black New Yorkers are excluded from voting due to a felony conviction at over five times the rate of non-Black New Yorkers. For Latino New Yorkers, their voter exclusion rate is almost twice that of non-Latino New Yorkers.

Voter Exclusion Rates in New York by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Source: Uggen, C. Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R. & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

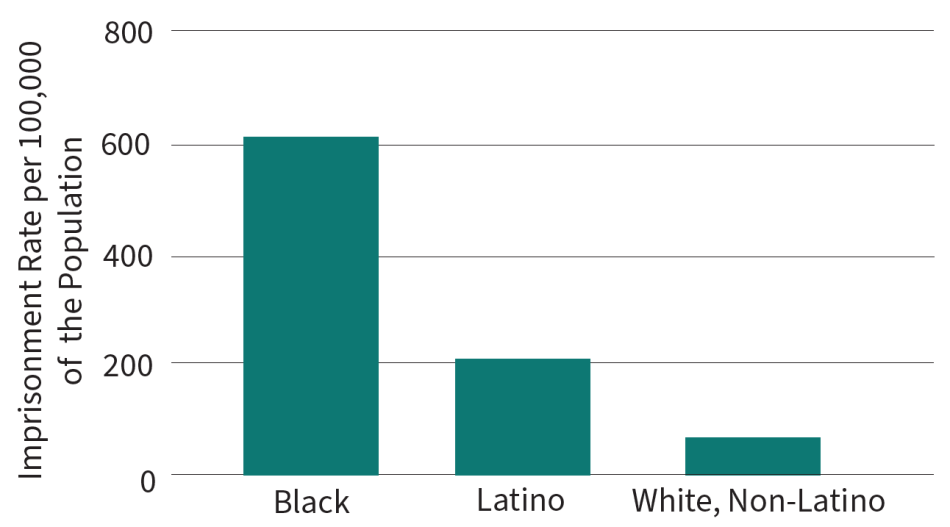

Imprisonment Rates in New York by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Source: New York Department of Corrections (2025). Incarcerated profile report as at March 1st, 2025 – table 2. New York Department of Corrections; U.S. Census Bureau (2023). Hispanic or Latino origin by race. American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables, table B03002. U.S. Census Bureau.

This stark racial disparity in voting access – where almost 50% of disenfranchised New Yorkers are Black and 24% are Latino – is driven by inequalities in the New York criminal legal system.2 To ameliorate this racial injustice and protect its democratic values, New York lawmakers should follow the lead of Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC and extend voting rights to all citizens.

Expanding Voting Rights in New York Is a Racial Justice Issue

Black and Latino people experience disproportionate rates of incarceration in New York. Black New Yorkers are imprisoned at a rate over 8.5 times that of white New Yorkers. For Latino residents of New York, the imprisonment rate is almost three times that of white New Yorkers.3

Bias and discrimination in the justice system lock Black and Latino people out of the democratic process. Racial disparities in New York’s criminal legal system go beyond differences in criminal offending and stem from bias in police arrests, courtroom proceedings, and prison discipline.4

Despite the termination of New York City’s broad stop-and-frisk program, bias persists in the city’s policing system, and Black and Latino people are disproportionately targeted under lower standards of suspicion.5 In 2018, Black people in New York City were stopped, arrested, and given summonses at nearly six times the rate of white people.6

Racial bias is also rampant inside New York state’s prisons, which can contribute to racial disparities in the duration of prison sentences. A 2022 report by the Inspector General of the State of New York, Lucy Lang, found disparity in how often guards discipline Black and Latino people compared to their white counterparts.7 Bias in prison discipline prevents incarcerated people from accessing jobs and educational programs that improve their chances for parole.8 During first-time parole hearings between 2013 and 2016, less than one in six incarcerated Black people were released, as compared to one in every four incarcerated white people.9 Every parole denial likely results in an additional two years in prison, increasing the amount of time that people are locked out of their right to vote.

Promote Voting Rights for All New Yorkers

Felony disenfranchisement has been a part of New York’s constitution since 1821.10 After the end of the Civil War, New York’s voting qualifications became increasingly restrictive. With the passage of the 14th and 15th amendments, New York changed the language in its laws to require disenfranchisement for people convicted of crimes.11 New York’s felony disenfranchisement laws are part of a racist past built to support white supremacy and undermine true democratic representation for all New Yorkers.

The right to vote in prison is recognized as an essential democratic practice inside and outside of the United States. In Maine and Vermont, people convicted of felonies never lose their right to vote. In both states, people in prisons can register (and remain registered) at their pre-incarceration address, and can request absentee ballots by mail.12 Puerto Rico has allowed people in jail to vote since 1980.13 In 2024, The Sentencing Project, ACLU, and Human Rights Watch found that the United States was more restrictive than over half of 136 countries surveyed regarding exclusion from the right to vote due to criminal convictions.14

Supporting Voting Rights Improves Public Safety

Research shows that an opportunity to participate in democracy has the potential to reduce one’s perceived status as an “outsider.” The act of voting can have a meaningful and sustaining positive influence on justice-impacted citizens by making them feel they belong to a community.15 Having a say and a stake in the life and well-being of your community is at the heart of our democracy.

Re-enfranchisement can facilitate successful re-entry and reduce recidivism. The University of Minnesota’s Christopher Uggen and New York University’s Jeff Manza find that among people with a prior arrest, there are “consistent differences between voters and non-voters in rates of subsequent arrest, incarceration, and self-reported criminal behavior.”16 Research also suggests that having the right to vote immediately after incarceration matters for public safety. Individuals in states that continued to restrict the right to vote after incarceration were found to have a higher likelihood of experiencing a subsequent arrest compared to individuals in states who had their voting rights restored post-incarceration.17 Given re-enfranchisement misinformation and obstacles facing justice-impacted citizens upon re-entry into our communities, one path to bolster public safety and promote prosocial identities is to preserve voting rights during incarceration.

Allowing people to vote, including persons completing felony sentences in prisons or jails, prepares them for more successful reentry and bolsters a civic identity. By ending disenfranchisement as a consequence of incarceration, New York can improve public safety while also promoting reintegrative prosocial behaviors.

New York Can Strengthen its Democracy by Restoring the Right to Vote

Excluding an entire population of people from exercising their right to vote undermines democracy. Incarcerated people in New York are counted in the U.S. census—in the districts in which they resided at the time of their arrest18—and tallied to draw political maps. But, because they cannot vote, their needs and interests often go unaddressed. The importance of being able to vote while serving a felony-level sentence in prison or jail goes beyond participation in state and federal elections to different domains of everyday life. For example, parents should be able to vote in their child’s school board elections even while incarcerated.19

Re-enfranchising those excluded from voting due to felony convictions would enable New York to fulfil its obligations under its own state constitution, ensuring that “no member of this state shall be disfranchised [sic], or deprived of any of the rights or privileges secured to any citizen thereof,”20 due to outdated laws and practices rooted in racist histories. New York should join Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC in ensuring all of their citizens can participate in our democratic process. New York should advance racial justice and community safety by re-enfranchising its entire voting age population.

| 1. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 3. | New York Department of Corrections (2025). Incarcerated profile report as at March 1st, 2025 – table 2. New York Department of Corrections; U.S. Census Bureau (2023). Hispanic or Latino origin by race. American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables, table B03002. U.S. Census Bureau. |

| 4. | Ghandnoosh, N. (2015). Black lives matter: Eliminating racial disparity in the criminal justice system. The Sentencing Project. |

| 5. | Zimaroth, P. (2020). Eleventh report of the independent monitor. CCR Justice. |

| 6. | Scrivener, L., Meizlish, A., Bond, E., & Chauhn, P. (2020). Tracking enforcement trends in New York City: 2003-2018. John Jay College of Criminal Justice. |

| 7. | Lang, L. (2022). Racial disparities in the administration of discipline in New York state prisons. State of New York Offices of the Inspector General. |

| 8. | Schwirtz, M., Winerip, M., & Gebeloff, R. (2016, Dec 3). The scourge of racial bias in New York state’s prisons. The New York Times. |

| 9. | Schwirtz, M., Winerip, M., & Gebeloff, R. (2016, Dec 3). The scourge of racial bias in New York state’s prisons. The New York Times. |

| 10. | Wood, E., Budnitz, L., & Malhotra, G. (2009). Jim Crow in New York. Brennan Center for Justice. |

| 11. | Wood, E., Budnitz, L., & Malhotra, G. (2009). Jim Crow in New York. Brennan Center for Justice. |

| 12. | White, A., & Nguyen, A. (2020). Locking up the vote? Evidence from Maine and Vermont on voting from prison. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. |

| 13. | San Diego Union-Tribune. (2016, August 23). Thousands of Puerto Rico inmates vote in Republican primary. The San Diego Union-Tribune. |

| 14. | Porter, N. D., Parker, A., Walk, T., Topaz, J., Turner, J., Smith, C., LaRonde-King, M., Pearce, S., & Ebenstein, J. (2024). Out of step: U.S. policy on voting rights in global perspective. The Sentencing Project. |

| 15. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558. |

| 16. | Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2004). Voting and subsequent crime and arrest: Evidence from a community sample. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 36(1), 193-216. |

| 17. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project. |

| 18. | New York State Senate. (2010, August 4). Senate passes bill to end prison gerrymandering in New York. New York State Senate. |

| 19. | Liebelson, D. (2019, September 6). In prison, and fighting to vote. The Atlantic. |

| 20. |