Oregon Should Restore Voting Rights to Over 13,400 Citizens

In Oregon, over 13,400 adults do not have the right to vote because they are incarcerated in prison or jail due to a felony conviction.

Related to: Voting Rights, State Advocacy

In Oregon, over 13,400 adults do not have the right to vote because they are incarcerated in prison or jail due to a felony conviction. Oregon’s rate of felony disenfranchisement—affecting 423 in every 100,000 voting eligible adults—is higher than that of neighboring Washington (284 in 100,000) and California (374 in 100,000).1

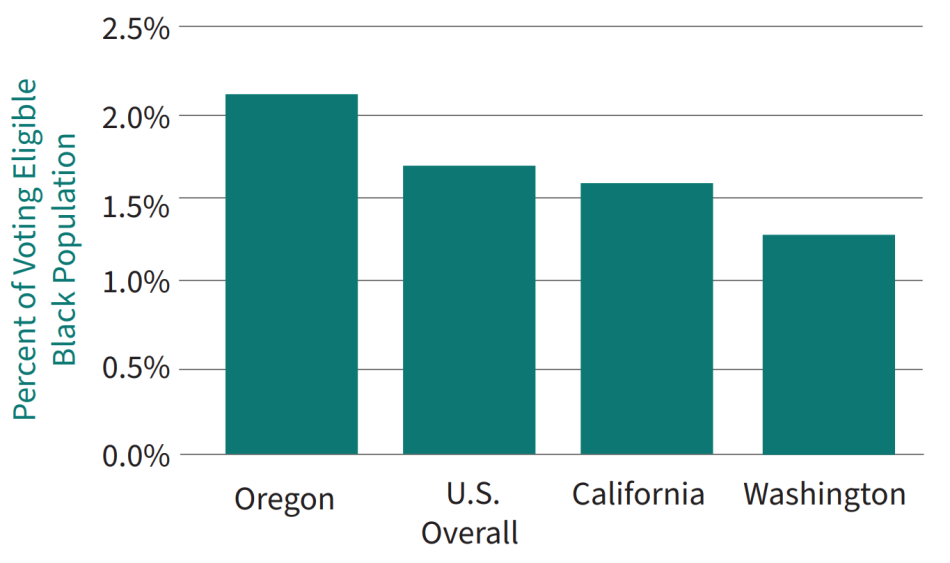

Disenfranchisement Rates for Black Citizens, 2024

Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

Oregon’s disenfranchisement of incarcerated people disproportionately harms Black citizens. While 1.8% of Oregon’s population is Black, 8.7% of its eligible voters who are banned from voting are Black.2 Oregon disenfranchises its Black citizens at a higher rate than the overall U.S. national average (2.13% versus 1.70%), and at a higher rate than Washington and California.3

To ameliorate this racial injustice and protect its democratic values, Oregon should follow the lead of Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC and extend voting rights to all citizens with felony convictions, including persons completing felonies in prisons or jails.

Racial Injustice in Oregon’s Criminal Legal System Causes Disparities in Disenfranchisement

Often viewed as a politically progressive state, Oregon has a sordid history of racial exclusion. Black people were banned from living in Oregon in 1844 before it established statehood.4 Those who were illegally in Oregon could be subjected to lashing, which was replaced by a period of forced labor and then banishment.5 In 1857, during a constitutional convention in Salem, the legislative assembly banned new Black residents, banned Black Oregonians from voting, and implemented felony disenfranchisement laws.6 When Oregon became the 33rd state in the union in 1859, it was the only state admitted with racist exclusion laws in the state constitution.7

The disproportionate incarceration of Black Oregonians – 8.1% of the prison population yet 1.8% of the overall population – is a key driver of racial disparity in felony disenfranchisement.8 These disparities in incarceration go beyond differences in criminal offending and result from persistent discriminatory practices throughout Oregon’s criminal legal system. Examples include:

- Data compiled by the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) reveal that the Gun Violence Reduction Team – a PPB specialty unit which used traffic stops to tackle gun-related crimes in the City of Portland – disproportionately stopped Black residents. Out of 1,605 stops citywide in 2019, 52% were Black residents in a city that is only 6% Black.9 When residents were searched, White residents were more frequently found with contraband.

- Drug possession enforcement has resulted in a disproportionate number of arrests and convictions of Black and Indigenous Oregonians compared to whites even though drug usage patterns do not substantially differ by race.10

Oregon should safeguard democratic rights and not allow its racially disparate criminal legal system to restrict voting rights.

Supporting Voting Rights Improves Public Safety

Research shows that an opportunity to participate in democracy has the potential to reduce one’s perceived status as an “outsider.” The act of voting can have a meaningful and sustaining positive influence on justice-impacted citizens by making them feel they belong to a community.11 As reinforced by Representative Khanh Pham, the first Vietnamese-American legislator in Oregon:

The ability to vote while incarcerated, reminds people that they are still meaningful members of society, and encourages them towards civic participation. Incarcerated folks are directly impacted by elections. From their meals to their medical care to the school districts which their children attend, the laws we create and amend will continue to govern our constituents regardless of their status and location. Oregon should respect the voices of all Oregonians, including those who are incarcerated.12

Having a say and a stake in the life and well-being of your community is at the heart of our democracy.

Re-enfranchisement can facilitate successful re-entry and reduce recidivism. The University of Minnesota’s Christopher Uggen and New York University’s Jeff Manza find that among people with a prior arrest, there are “consistent differences between voters and non-voters in rates of subsequent arrest, incarceration, and self-reported criminal behavior.”13 Research also suggests having the right to vote immediately after incarceration matters for public safety. Individuals in states that continued to restrict the right to vote after incarceration were found to have a higher likelihood of experiencing a subsequent arrest compared to individuals in states who had their voting rights restored post-incarceration.14 Given re-enfranchisement misinformation and obstacles facing justice-impacted people upon re-entry into our communities, one path to bolster public safety and promote prosocial identities is to preserve voting rights during incarceration.

Allowing people to vote, including persons completing felony sentences in prison or jail, prepares them for more successful reentry and bolsters a civic identity. By ending disenfranchisement as a consequence of incarceration, Oregon can improve public safety while also promoting reintegrative prosocial behaviors.

Oregon Can Strengthen its Democracy by Restoring the Right to Vote

Since 1997, 26 states and the District of Columbia have expanded voting rights to people with felony convictions resulting in over 2 million Americans having regained the right to vote.15 When the state of Oregon takes away the ability to vote, it also removes an important avenue, especially Black people, to advocate for their own needs and the needs of their communities.

Oregon should join Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, D.C. in ensuring all of their citizens can participate in our democratic process. Oregon should continue advancing racial justice by re-enfranchising all voting age citizens.

| 1. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project; Voting eligible adults are defined as individuals who are at least 18 years old and a U.S. citizen |

|---|---|

| 2. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project; U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). Hispanic or Latino Origin by Race. American Community Survey, ACS 5-Year Estimates Detailed Tables, Table B03002. |

| 3. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 4. | Oregon Secretary of State. (n.d.). National and Oregon Chronology of Events. |

| 5. | Oregon Secretary of State. (n.d.). National and Oregon Chronology of Events. |

| 6. | Oregon Secretary of State. (n.d.). National and Oregon Chronology of Events. |

| 7. | Oregon Secretary of State. (n.d.). National and Oregon Chronology of Events. |

| 8. | This number was calculated using population statistics from the Oregon Department of Corrections. (2024). 2024 Quick Facts. |

| 9. | Portland Police Bureau. Gun Violence Reduction Team Supplemental Report – 2019. https://default.salsalabs.org/Tb31fcca3-93f7-40e2-90db-67427f5a4ada/31aaa82a-f4af-412d-8402-8659f4342033; Bernstein, M. (2020, November 20). In 2019, the Portland police Gun Violence team made 1,600 stops. More than half were Black people. https://www.oregonlive.com/crime/2020/11/in-2019-the-portland-police-gun-violence-team-made-1600-stops-more-than-half-were-black-people.html?eType=EmailBlastContent&eId=01d27595-1c89-4538-b8e4-61cff2adc3b0 |

| 10. | Edwards, E., et al. (2020). A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform. https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/042020-marijuanareport.pdf |

| 11. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 12. | Pham, K. (2021). Testimony in support of SB 571. https://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2021R1/Downloads/PublicTestimonyDocument/7513 |

| 13. | Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2004). Voting and subsequent crime and arrest: Evidence from a community sample. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 36(1), 193-216. |

| 14. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 15. | Porter, N. & McLeod, M. (2023). Expanding the vote: State felony disenfranchisement reform, 1997-2023. The Sentencing Project. |