Tennessee Should Restore Voting Rights to Nearly 400,000 Citizens

Tennessee denies almost 400,000 people the right to vote due to a felony-level conviction – the third largest disenfranchised population in the country, behind only Florida and Texas.

Related to: Voting Rights, State Advocacy, Racial Justice

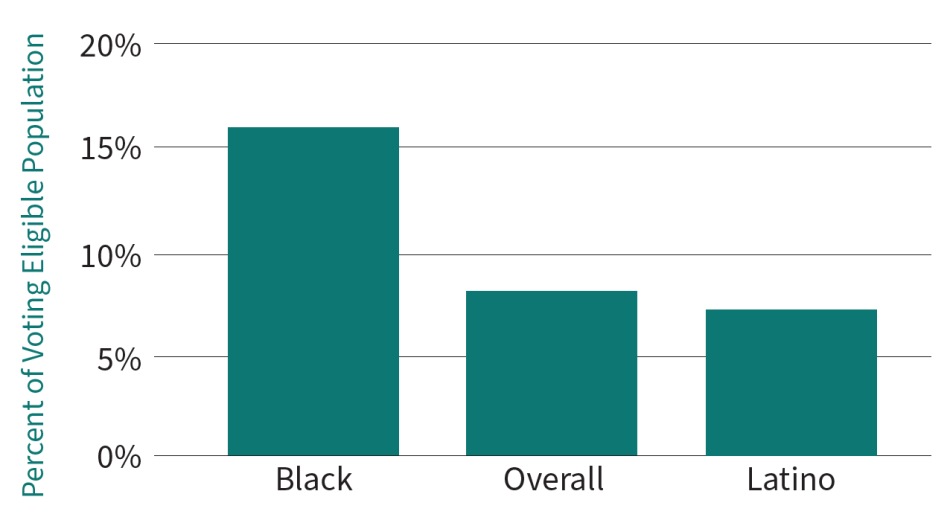

Tennessee denies almost 400,000 people the right to vote due to a felony-level conviction – the third largest disenfranchised population in the country, behind only Florida and Texas.1 The overwhelming majority of disenfranchised Tennesseans, over 300,000 citizens, have completed their sentence but remained blocked from the ballot box.2 Tennessee’s voting ban also results in stark racial injustices in ballot access. Tennessee has the country’s highest rates of disenfranchisement for both Black and Latino voting eligible Americans – 16% of Black and 7% of Latino residents.3

To ameliorate this racial injustice, Tennessee lawmakers should extend voting rights to all people affected by the criminal legal system and protect its democratic values.

Voter Exclusion Rates in Tennessee by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Source: Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R. & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

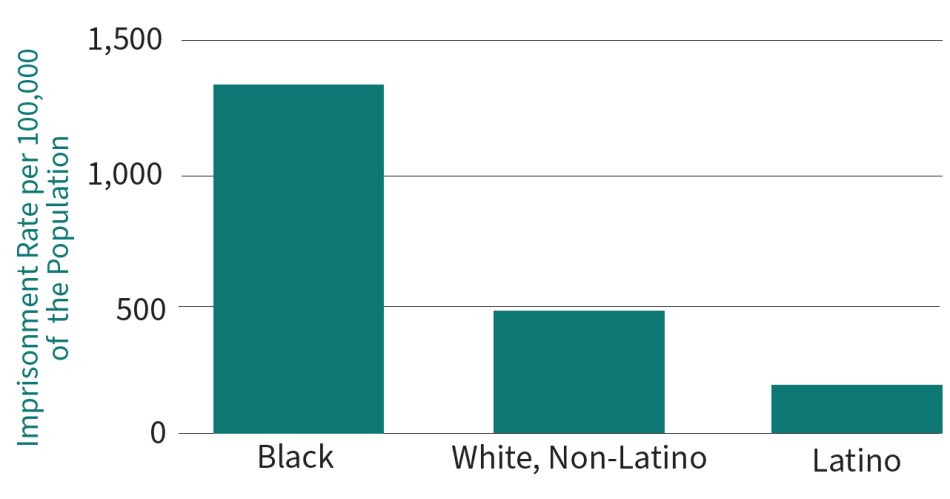

Imprisonment Rates in Tennessee by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Source: Tennessee Department of Corrections (2024). Statistical abstract. Tennessee Department of Corrections; U.S. Census Bureau (2023). American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables – table B03002. U.S. Census Bureau.

Expanding Voting Rights in Tennessee is a Racial Justice Issue

People of color are disproportionately disenfranchised in Tennessee, because they are overrepresented in its criminal legal system. While Black Tennesseans make up 16% of Tennessee’s population, they represent 36% of the prison population and 38% of people on parole.4

Racial bias and discrimination in the justice system lock people of color out of the democratic process. In 2020, the racial injustice of the Tennessee legal system gained the attention of the state’s supreme court, resulting in the creation of a two-year plan by the Access to Justice Commission to reduce systemic discrimination.5 In its 2022 update, the Commission acknowledged further efforts and strategies that must be undertaken to continue to address such significant discrimination and poor treatment of Tennesseans of color in the justice system.6

Racial disparities in Tennessee’s criminal legal system go beyond differences in criminal offending and stem from factors including implicit bias affecting police and prosecutorial decision-making.7 For example, Nashville and Memphis police have arrested Black Tennesseans at roughly three times the rate of non-Black residents, targeting communities of color for low-level arrests.8 As recently as 2019, Tennessee was one of only 10 states in which all elected prosecutors were white.9

Tennessee’s Felony Voting Laws Remain Outdated and Inaccessible

Tennessee’s complicated and protracted voting restoration process prevents many Tennesseans with felony convictions from regaining their right to vote. Under Tennessee’s current law, people convicted of felonies can regain their voting rights only after completing their sentence and repaying court fees and outstanding child support.10 However, voting rights are not automatically restored when citizens become re-eligible. Those wishing to apply for voting restoration must file a separate form for each felony conviction.11 The forms must be completed by a probation or parole officer, or criminal court clerk—many of whom have not been trained on the process.12 Regulations for voting restoration vary across county lines; there is no universal process through which to attain a Certificate of Restoration, nor a uniform method of determining eligibility.13 Rejections come with no explanatory statements. There are no official means for appeal.14

Tennessee’s voting restoration process is also not open to everyone with a felony conviction. The state constitution specifies that citizens convicted of “infamous” crimes—as classified by trial judges—can be permanently disenfranchised.15 Eligibility for voting rights restoration depends upon the type of offense and year of conviction, meaning that Tennessee does not have one universal law regarding enfranchisement.16 Many Tennesseans with felony convictions are uninformed of their eligibility for voting restoration. For those who are aware of their rights, monetary and bureaucratic barriers prevent many from regaining their right to vote.

Supporting Voting Rights Improves Public Safety

Research shows that an opportunity to participate in democracy has the potential to reduce one’s perceived status as an “outsider.” The act of voting can have a meaningful and sustaining positive influence on justice-impacted citizens by making them feel they belong to a community.17 Having a say and a stake in the life and well-being of your community is at the heart of our democracy.

Re-enfranchisement can facilitate successful re-entry and reduce recidivism. The University of Minnesota’s Christopher Uggen and New York University’s Jeff Manza find that among people with a prior arrest, there are “consistent differences between voters and non-voters in rates of subsequent arrest, incarceration, and self-reported criminal behavior.”18 Research also suggests having the right to vote immediately after incarceration matters for public safety. Individuals in states which continued to restrict the right to vote after incarceration were found to have a higher likelihood of experiencing a subsequent arrest compared to individuals in states who had their voting rights restored post-incarceration.19 Given re-enfranchisement misinformation and obstacles facing justice-impacted citizens upon re-entry into our communities, one path to bolster public safety and promote prosocial identities is to preserve voting rights during incarceration.

Allowing people to vote, including persons completing felony sentences in prisons or jails, under community supervision for a felony conviction, and those who have completed their sentences, prepares them for more successful reentry and bolsters a civic identity. By ending disenfranchisement, Tennessee can improve public safety while also promoting reintegrative prosocial behaviors.

Tennessee Can Preserve its Democracy by Restoring the Right to Vote

Excluding an entire population of people from exercising their right to vote undermines democracy. From 2018 to 2023, only an estimated 3,350 Tennesseans with felony convictions successfully restored their voting rights—around 1% of people who had completed their sentence.20 Studies have found that voter turnout is greater in states that actively inform formerly incarcerated people of their rights, dispelling notions that people with convictions do not wish to engage in the political process.21

Relieving the barriers to enfranchisement for Tennesseans with felony convictions requires a change in the law. In 2021, The Campaign Legal Center and the Tennessee NAACP brought a lawsuit against Tennessee, arguing that the failures of the state’s restoration process violate the Equal Protection Clause and the National Voter Registration Act.22 Natasha Baker of Equal Justice Under Law, a non-profit law organization dedicated to achieving equality in the criminal justice system and ending cycles of poverty,23 states: “There is still a long road ahead, but the path to restoring the right to vote for hundreds of thousands of Tennesseans just got clearer.”24 Unfortunately, the case was dismissed in September 2024, following a 30-day stay granted by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, which led to Campaign Legal Center & the Tennessee NAACP opting to withdraw their claims.25 Tennessee’s voting rights advocates continue to face exceptional barriers in re-enfranchisement campaigns and legal options for rights restoration.

Universal voting promotes fair and equal representation and establishes trust between communities and their governments. Tennessee should take immediate action to remedy its outdated restoration system and re-enfranchise its entire voting eligible population, regardless of criminal legal involvement. This would bring it up to speed with its own state constitution’s provision that “all power is inherent in the people, and all free governments are founded on their authority, and instituted for their peace, safety, and happiness.”26 Tennessee should join Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC in ensuring all of their citizens can participate in our democratic process.

| 1. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R. & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Lerner, K. (2023, September 7). The states where it’s impossible to vote if you have a felony conviction. The Guardian. Note that there are specific felonies, identified by the Tennessee Secretary of State, for which a conviction will lead to a permanent exclusion from the right to vote: Hargett, T. (2025). Restoration of voting rights. Tennessee Secretary of State. |

| 3. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R. & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project; Voting eligible adults are defined as individuals who are at least 18 years old and a U.S. citizen. |

| 4. | Tennessee Department of Corrections (2024). Statistical abstract. Tennessee Department of Corrections; U.S. Census Bureau (2023). American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables – table B03002. U.S. Census Bureau; Kaeble, D. (2024). Probation and parole in the United States, 2022. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 5. | Tennessee Supreme Court Access to Justice Commission. (2020). 2018-2022 strategic plan: 2020 update. Justice for all: A Tennessee Supreme Court initiative. |

| 6. | Tennessee Supreme Court Access to Justice Commission. (2022). Strategic plan 2022-24. Justice for all: A Tennessee Supreme Court initiative. |

| 7. | Ghandnoosh, N. (2015). Black lives matter: Eliminating racial disparities in the criminal justice system. The Sentencing Project. |

| 8. | Reicher, M. (2016, July 28). Racial disparities in arrest: How does Nashville compare? The Tennessean. |

| 9. | Reflective Democracy Campaign. (2019). Tipping the scales: Challengers take on the old boys’ club of elected prosecutors. Reflective Democracy Campaign. |

| 10. | Friedman, A. (2021, February 8). Tennessee says most former felons can vote. They disagree. Jackson Sun. |

| 11. | Hargett, T. (2025). Restoration of voting rights. Tennessee Secretary of State. |

| 12. | Lewis, N. (2019, September 19). Tennessee’s voter restoration gauntlet. The Marshall Project. |

| 13. | Lyon, G. (2020, July 21). CLC sues Tennessee for restricting citizens’ right to vote. Campaign Legal Center. |

| 14. | TN NAACP vs. Lee, 3:20-cv-01039 (Tennessee District Court December 3, 2020). |

| 15. | Hargett, T. (2025). Restoration of voting rights. Tennessee Secretary of State. |

| 16. | Hargett, T. (2025). Restoration of voting rights. Tennessee Secretary of State. |

| 17. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558. |

| 18. | Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2004). Voting and subsequent crime and arrest: Evidence from a community sample. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 36(1), 193-216. |

| 19. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project. |

| 20. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R. & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 21. | Lewis, N., & Calderón, A. R. (2021, June 23). Millions of people with felonies can now vote: Most don’t know it. The Marshall Project. |

| 22. | TN NAACP vs. Lee, 3:20-cv-01039 (Tennessee District Court December 3, 2020). |

| 23. | Equal Justice Under Law. (n.d.) Our mission. Equal Justice Under Law. |

| 24. | Baker, N. (2022, April 8). Class action challenging voter suppression in Tennessee survives motion to dismiss. Equal Justice Under Law. |

| 25. | American Redistricting Project. (2024, September 25). Tennessee State Conference of the NAACP et al. v. William B. Lee. American Redistricting Project; Justia Law. (2024). Tennessee Conference of the NAACP v. Lee, no. 24-5546 (6th cir. 2024). Justia Law. |

| 26. |