Texas Should Restore Voting Rights to Nearly Half a Million Citizens

Texas laws are particularly restrictive—prohibiting individuals from voting who are on felony probation, parole, or incarcerated for a felony-level conviction.

Related to: Voting Rights, State Advocacy

Over 479,000 Texans cannot vote due to a felony conviction – the second largest disenfranchised population in the country, behind only Florida.1 Texas laws are particularly restrictive—prohibiting individuals from voting who are on felony probation, parole, or incarcerated for a felony-level conviction. Driving Texas’s high disenfranchisement rate is its ban on voting for over 327,000 people completing their sentence on felony probation or parole. People of color in particular are more likely to be prohibited from voting because of the stark racial disparities in the Texas criminal legal system.

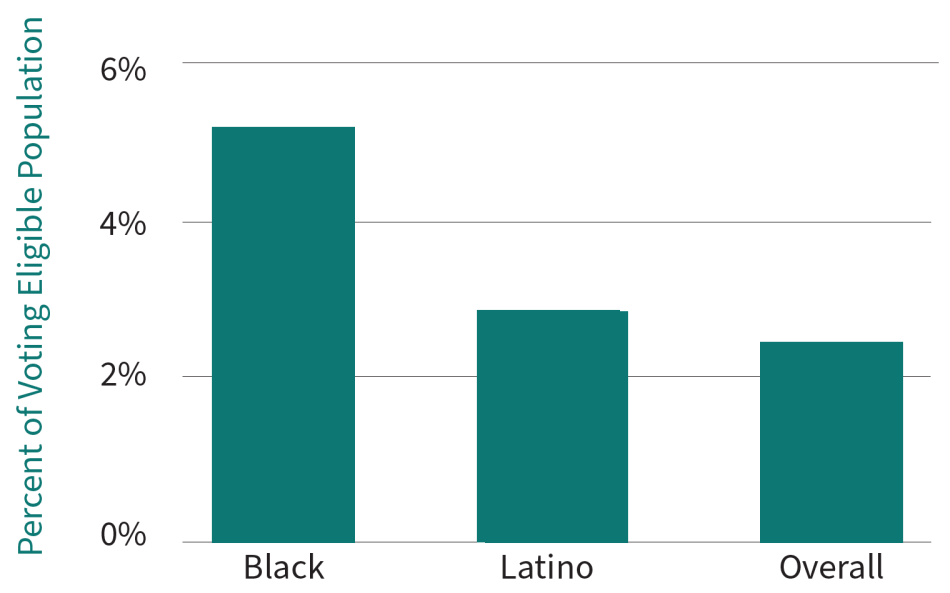

Voter Exclusion Rates in Texas by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

Texas’s voting ban results in stark racial injustices in ballot access. Voting eligible Black Texans are roughly 2.5 times as likely as non-Black Texans to lose their right to vote due a felony-level conviction. Latino Texans are 1.2 times as likely as non-Latino Texans to lose their right to vote due to a felony-level conviction.2

The law restricting voting for people with felony convictions undermines Texas’s democracy and extends the racial injustice embedded in the criminal legal system to its electoral system. To ameliorate this racial injustice and protect its democratic values, Texas should follow the lead of Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC, and extend voting rights to all citizens, including persons completing felony sentences in prisons and jails and under community supervision for a felony conviction.

Supporting Voting Rights Improves Public Safety

Research shows that an opportunity to participate in democracy has the potential to reduce one’s perceived status as an “outsider.” The act of voting can have a meaningful and sustaining positive influence on justice-impacted citizens by making them feel they belong to a community.3 Having a say and a stake in the life and well-being of your community is at the heart of our democracy.

Re-enfranchisement can facilitate successful re-entry and reduce recidivism. The University of Minnesota’s Christopher Uggen and New York University’s Jeff Manza find that among people with a prior arrest, there are “consistent differences between voters and non-voters in rates of subsequent arrest, incarceration, and self-reported criminal behavior.”4 Research also suggests having the right to vote immediately after incarceration matters for public safety. Individuals in states which continued to restrict the right to vote after incarceration were found to have a higher likelihood of experiencing a subsequent arrest compared to individuals in states who had their voting rights restored post-incarceration.5 Given re-enfranchisement misinformation and obstacles facing justice-impacted citizens upon re-entry into our communities, one path to bolster public safety and promote prosocial identities is to preserve voting rights during incarceration and while on community supervision.

Allowing people to vote, including persons completing felony sentences in prisons or jails and under community supervision for a felony conviction, prepares them for more successful reentry and bolsters a civic identity. By ending disenfranchisement as a consequence of a felony conviction, Texas can improve public safety while also promoting reintegrative prosocial behaviors.

Expanding Voting Rights in Texas is a Racial Justice Issue

Texas law has disenfranchised people convicted of felonies since 1845.6 Throughout its history the law has had a racially disparate impact, both intentionally and unintentionally. In an 1897 speech at the National Prison Congress, George T. Winston, then-President of the University of Texas, argued that “to protect their property and civilization,” the “Southern white population” would need to incarcerate more Black Americans.7 This terrible legacy of racist “Jim Crow” laws lives on today.

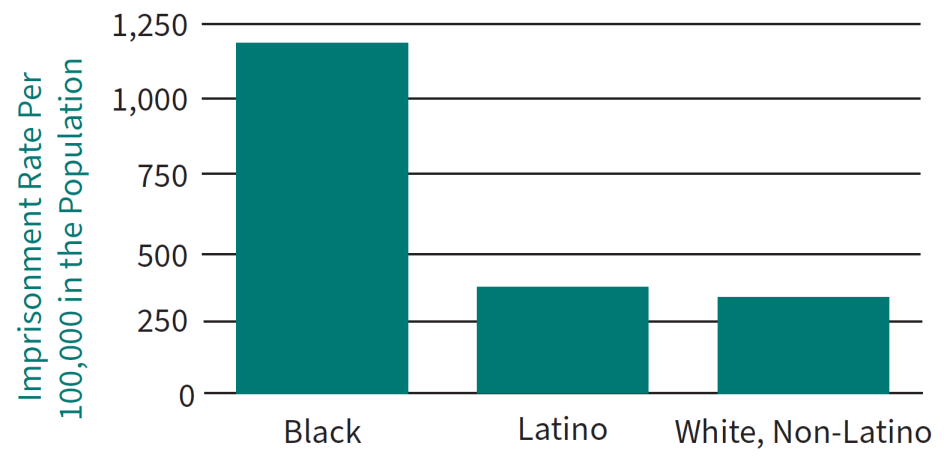

Imprisonment Rate in Texas by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Texas Department of Criminal Justice. (August 31, 2024). Statistical report: Fiscal year 2024; U.S. Census Bureau. Hispanic or Latino Origin by Race. American Community Survey, ACS 5-Year Estimates Detailed Tables, Table B03002, 2023.

Black Texans are over three times as likely to be imprisoned as white Texans.8 During the early years of the “War on Drugs,” Black people, despite using drugs at similar rates as white people, accounted for 81% of the increase in Texas’s prison population for drug offenses.9 Additionally, research has shown that Black Texans often receive longer sentences than white Texans for similar drug-related crimes.10

The systemic inequities extend beyond incarceration. Following the 2015 death of Sandra Bland in the Waller County Jail, Texas passed the Sandra Bland Act in 2017, which aimed to address racial profiling and collect traffic stop data. In a 2020 analysis of six million police stops, researchers at Texas A&M University found that Latinos were the most likely to be searched for contraband even though police were more likely to find contraband on searched white Texans. Additionally, police disproportionately arrested both Black and Latino individuals compared to white individuals when contraband was discovered. Despite some improvements in data reporting, many police agencies failed to reliably report race and ethnicity data.11

From arrest to sentencing, people of color have disproportionate contact with the criminal legal system, which drives disparities in felony disenfranchisement and ultimately prevents the Black and Latino community from having its rightful say in Texas’s democratic process.12

Texas Should Implement Universal Enfranchisement Laws

While Texas formally ended lifetime felony disenfranchisement in 1983, it has been slow to keep up with further reforms across the country.13 People convicted of felonies were forced to endure years-long waiting periods after the end of their sentences to regain the right to vote, until waiting periods were eliminated entirely in 1997.14 Yet, in 2007, the governor vetoed a bill requiring the state to notify people of their restored voting rights.15 This raises serious concerns about Texas’s commitment to the values necessary to support a thriving democracy.

Blocking access to the ballot box betrays the democratic process and the voice of the people. Texas should ensure all of its citizens can participate in our democratic process.

| 1. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked Out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project; Voting eligible adults are defined as individuals who are at least 18 years old and a U.S. citizen. |

| 3. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 4. | Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2004). Voting and subsequent crime and arrest: Evidence from a community sample. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 36(1), 193-216. |

| 5. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 6. | Brooks, G. (2005). Felon disenfranchisement: Law, history, policy, and politics. Fordham Urban Law Journal, 32(5), 101-148. https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol32/iss5/3 |

| 7. | Perkinson, P. (2010). Texas tough: The rise of America’s prison empire. New York: Metropolitan Books. |

| 8. | Nellis, A. (2021). The color of justice: Racial and ethnic disparity in state prisons. The Sentencing Project. |

| 9. | Porter, N. (2008). The politics of felon disenfranchisement in Texas. The Electorate. http://blackelectorate.com/articles.asp?ID=2028 |

| 10. | Curry, T., & Corral-Comacho, G. (2008). Sentencing young minority males for drug offenses: Testing for conditional effects between race/ethnicity, gender, and age during the U.S. war on drugs. Punishment and Society, 10(3), 253-276. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474508090231 |

| 11. | Del Carmen, A., Luo, F., Pollock, W., Chism, K., Gibson, C., Sibila, D., Frantzen, D., Steward, D., Petrowski, T., & Copes, B. (2021). 2020 racial profiling data analysis for the state of Texas. Institute for Predictive Analysis in Criminal Justice. |

| 12. | Ghandnoosh, N. (2015, February 3). Black lives matter: Eliminating racial disparities in the criminal justice system. The Sentencing Project. |

| 13. | Sennott, C. & Galliher, J. F. (2006). Lifetime felony disenfranchisement in Florida, Texas, and Iowa. Symbolic and Instrumental Law, Social Justice, 33(1), 79-94. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29768353 |

| 14. | Mcleod, M. (2018). Expanding the vote: Two decades of felony disenfranchisement reforms. The Sentencing Project. |

| 15. | HB 770. (2007). Relating to requiring the Texas Department of Criminal Justice to provide notice to certain persons of the right to vote. https://capitol.texas.gov/billlookup/Actions.aspx?LegSess=80R&Bill=HB770 |