Why We Must Restore Voting Rights to Over 16,000 Marylanders

Maryland should strengthen its democracy and advance racial justice by re-enfranchising its entire voting eligible population.

Related to: Voting Rights, State Advocacy

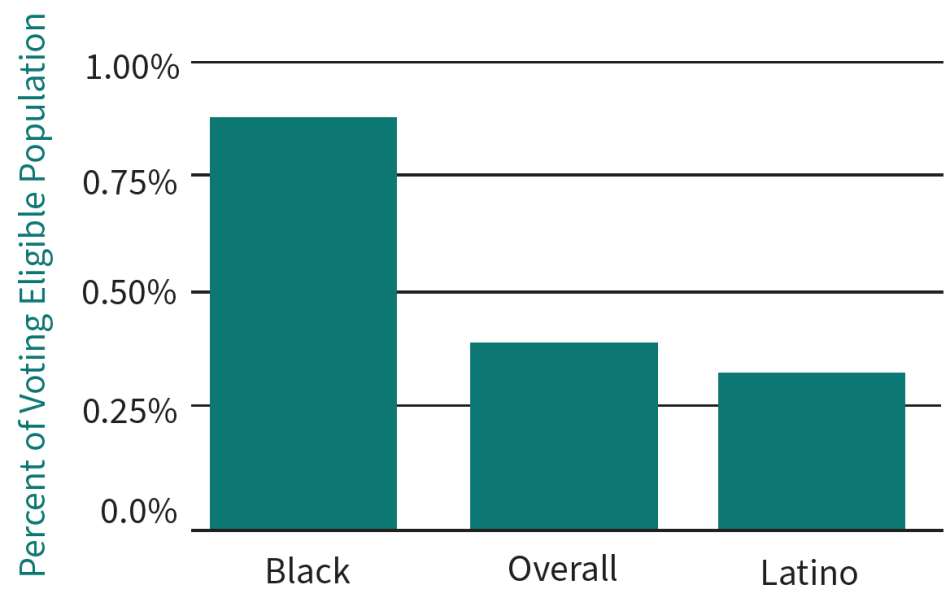

More than 16,000 Marylanders are banned from voting while serving a prison or jail term for a felony conviction.1 This voting ban strips Marylanders of their political voice. It falls heavily on people of color because of the stark racial disparities in the Maryland criminal legal system. Seventy percent of Maryland voters who are banned from casting a ballot due to a felony conviction are Black even though only 31% of the voting eligible population is Black.2

Voter Exclusion Rates in Maryland by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

Maryland’s voting ban results in stark racial injustices in ballot access. Voting eligible Black Marylanders are over five times as likely as non-Black Marylanders to lose their right to vote due to incarceration for a felony conviction.3

The law restricting voting for people with felony convictions undermines Maryland’s democracy and extends the racial injustice embedded in the criminal legal system to its electoral system. To ameliorate this racial injustice and protect its democratic values, Maryland should follow the lead of Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC, and extend voting rights to all, including persons completing their felony-level sentence in prison or jail.

Expanding Voting Rights in Maryland Is a Racial Justice Issue

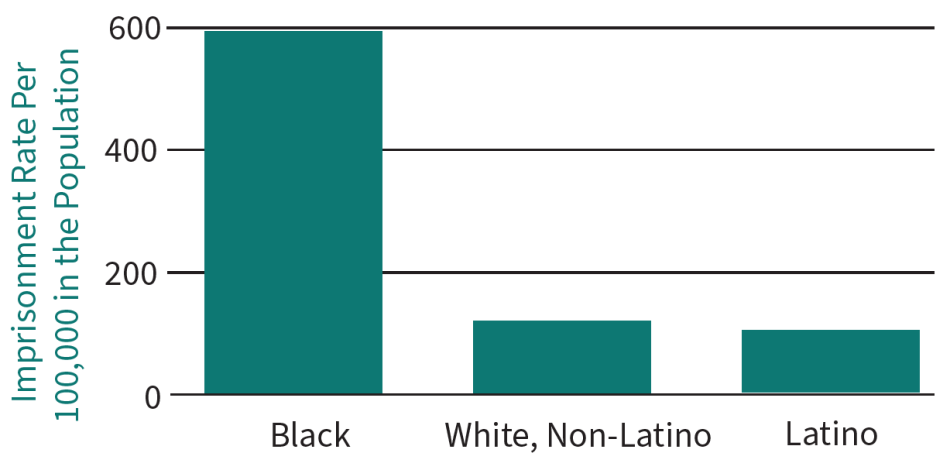

Voter exclusion is particularly acute for Black residents in Maryland due to their disproportionate incarceration for felony convictions. While 30% of the state’s population is Black, 72% of the prison population is Black. This means, in Maryland, Black residents are more than five times as likely as white residents to be in prison.4

Imprisonment Rate in Maryland by Race and Ethnicity, 2023

Maryland Department of Correction. (2023). Population data dashboard: Race and ethnicity [Data dashboard].; U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). Hispanic or Latino Origin by Race. American Community Survey, ACS 5-Year Estimates Detailed Tables, Table B03002.

Such disparities in incarceration go beyond differences in criminal offending and result from differential treatment throughout Maryland’s criminal legal system. The following examples illustrate the disparate effects of these practices on Black people in Maryland:

- Policing: Black individuals in Baltimore were disproportionately targeted by the Baltimore Police Department (BPD) in arrests, especially for drug possession, according to a report by the U.S. Department of Justice. From November 2010 to July 2015, BPD filed over 300,000 criminal charges in which the person’s race was known. Of those, Black individuals accounted for over 86% of all the filed criminal charges, despite making up only 63% of Baltimore’s population. For drug possession charges in particular, Black individuals were five times as likely than individuals of other races to be arrested and charged. Notably, drug usage rates in Baltimore were similar across racial groups and BPD’s rate of arresting Black individuals for drug offenses significantly exceeded rates seen in comparable cities.5

- Sentencing: Sentencing: Black and Latino individuals were more likely than white individuals to be incarcerated and receive longer sentences, particularly for firearm offenses, according to a report by the Maryland State Commission on Criminal Sentencing Policy. The Commission examined over 27,000 sentences from 2018 to 2020, comparing the frequency of incarceration and sentence lengths to Maryland’s sentencing guidelines. These guidelines provide judges with recommended ranges of incarceration time based on factors such as criminal history and case severity. However, Black and Latino individuals were more likely to face charges with mandatory minimums—fixed minimum sentences that eliminate judicial discretion. Mandatory minimums often resulted in longer sentences than judges might have imposed if they had flexibility under the sentencing guidelines. Even when mandatory minimums did not apply, judges tended to impose sentences at the harsher end of the guideline range more frequently for Black and Latino individuals than for white individuals.6

Racial disparity in incarceration is diluting the political voice of people of color. Maryland should safeguard democratic rights and not allow a racially disparate criminal legal system to restrict voting rights.

Supporting Voting Rights Improves Public Safety

Research shows that an opportunity to participate in democracy has the potential to reduce one’s perceived status as an “outsider.” The act of voting can have a meaningful and sustaining positive influence on justice-impacted people by making them feel they belong to a community.7 Having a say and a stake in the life and well-being of your community is at the heart of our democracy.

Re-enfranchisement can facilitate successful re-entry and reduce recidivism. The University of Minnesota’s Christopher Uggen and New York University’s Jeff Manza find that among people with a prior arrest, there are “consistent differences between voters and non-voters in rates of subsequent arrest, incarceration, and self-reported criminal behavior.”8 Research also suggests having the right to vote immediately after incarceration matters for public safety. Individuals in states that continued to restrict the right to vote after incarceration were found to have a higher likelihood of experiencing a subsequent arrest compared to individuals in states who had their voting rights restored post-incarceration.9 Given re-enfranchisement misinformation and obstacles facing justice-impacted people upon re-entry into our communities, one path to bolster public safety and promote prosocial identities is to preserve voting rights during incarceration.

Allowing people to vote, including persons completing felony sentences in prison or jail, prepares them for more successful reentry and bolsters a civic identity. By ending disenfranchisement as a consequence of incarceration, Maryland can improve public safety while also promoting reintegrative prosocial behaviors.

Ensuring Equal and Fair Representation

Ending felony disenfranchisement in Maryland is a natural extension of the work done over a decade ago when Maryland outlawed prison gerrymandering. The practice of prison gerrymandering is ingrained in the United States census system.

State and national legislative districts are redrawn every 10 years based on a count of every residence, but the Census Bureau counts incarcerated individuals as residents of their prisons rather than as residents of their home communities.10 Since each district must have a comparable population, voters who live in districts with large prison populations have disproportionate political power. Those districts tend to be more rural and white, while the districts who are disadvantaged by their residents being incarcerated elsewhere, and not counted as part of their community, tend to be urban and Black/Brown.11 This is especially true in Maryland. Before prison gerrymandering was outlawed, 40% of people incarcerated in state prisons were from Baltimore, but 90% of them were counted in another locality.12 Maryland was the first in the nation to end this undemocratic process in 2010,13 but the state still fails to realize its greatest potential by allowing incarcerated residents who are now counted in their home communities to actually cast ballots there.

Maryland has an opportunity to be a national trailblazer once again by combining its redistricting system with meaningful reforms that allow incarcerated Marylanders to have the same democratic say as their fellow citizens.

Maryland Can Strengthen its Democracy by Restoring the Right to Vote

Since 1997, 26 states and the District of Columbia have expanded voting rights to people with felony convictions resulting in over 2 million Americans having regained the right to vote.14 As part of this movement, in 2007, then-Governor Martin O’Malley signed the Voter Registration and Protection Act, restoring voting rights to an estimated 50,000 individuals in Maryland with felony convictions who had fully completed their sentences, including any felony probation or parole terms.15 Then in 2016, another 40,000 people who were on felony probation and parole regained their right to vote when legislators overrode Governor Larry Hogan’s veto on S.B. 340/H.B. 980.16

However, Maryland legislators still must take action to ensure that all eligible voters can fully participate in democracy. Marylanders who are currently incarcerated in jail or prison for a felony-level conviction do not have the right to vote. Excluding an entire population from exercising their right to vote erodes democracy and is not in accordance with Maryland’s declaration of rights that states “all Government of right originates from the People.”17 When the state of Maryland takes away the ability to vote, it also removes an important avenue, especially for Black people, to advocate for their own needs and the needs of their communities.

Maryland should strengthen its democracy and advance racial justice by re-enfranchising its entire voting eligible population.

| 1. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project; Voting eligible adults are defined as individuals who are at least 18 years old and a U.S. citizen. |

| 3. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 4. | Maryland Department of Correction. (2024). FY 2023 population overview: DOC inmate demographics [Data dashboard]; U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). Hispanic or Latino Origin by Race. American Community Survey, ACS 5-Year Estimates Detailed Tables, Table B03002. |

| 5. | U.S. Department of Justice. (2016). Investigation of the Baltimore City Police Department. |

| 6. | Maryland State Commission on Criminal Sentencing Policy. (2023). An assessment of racial differences in Maryland guidelines-eligible sentencing events. |

| 7. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 8. | Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2004). Voting and subsequent crime and arrest: Evidence from a community sample. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 36(1), 193-216. |

| 9. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 10. | Maschman, J., Morris, K., Ryan, P. S., & Eisman, D. (2018). Democracy behind bars. Common Cause. |

| 11. | Prison Policy Initiative. Prison gerrymandering project: The problem; Wagner, P., & Kopf, D. (2015). The racial geography of mass incarceration. Prison Policy Initiative. |

| 12. | Prison Policy Initiative. Prison gerrymandering project: The problem. |

| 13. | Prison Policy Initiative. Prison gerrymandering project: The problem. |

| 14. | Porter, N. & McLeod, M. (2023). Expanding the vote: State felony disenfranchisement reform, 1997-2023. The Sentencing Project. |

| 15. | Voter Registration and Protection Act, S.B. 488. (Md. 2007); Green, A. (2007, April 25). Felons gain right to vote. The Baltimore Sun. |

| 16. | S.B 340/H.B. 980. (Md. 2016); Lopez, T. (2016, Feb 9). Maryland takes big step forward on voting rights. Huffpost. |

| 17. |