Increasing Public Safety by Restoring Voting Rights

To promote public safety and enhance reintegration efforts, states should dismantle laws and policies that exclude justice-impacted people from participating in our democracy.

Related to: Voting Rights

Restoring voting rights for people with felony convictions can improve public safety. Voting is among a range of prosocial behaviors in which justice-impacted persons can partake, like getting a college education, that is associated with reduced criminal conduct.1 Among Americans with a history of criminal legal system involvement, having the right to vote or the act of voting is related to reduced recidivism.2 The re-entry process after incarceration improves because restoring voting rights gives citizens the sense that their voice can be heard in the political process, and contributes to building an individual’s positive identity as a community member.3

The studies featured in this brief underscore the beneficial impacts of restoring voting rights for all Americans who have been convicted of a felony, whether they are inside or outside of prison.4

“Anytime a member of a society is not afforded the right to express his or her opinions by way of the democratic process, we cannot achieve the ideals of democracy.” — Joel Castón

Introduction

Over 4.6 million Americans cannot vote due to a felony conviction – nearly four times as many people since the onset of mass incarceration in 1973.5 The forced exile of justice-impacted individuals from voting is a direct ramification of the U.S. prison population surge over the previous five decades.6 The United States is an international outlier both in its heavy reliance on the criminal legal system and its disenfranchisement of people in prisons and jails, those completing their sentences in the community, and millions of others who are no longer under correctional supervision.7

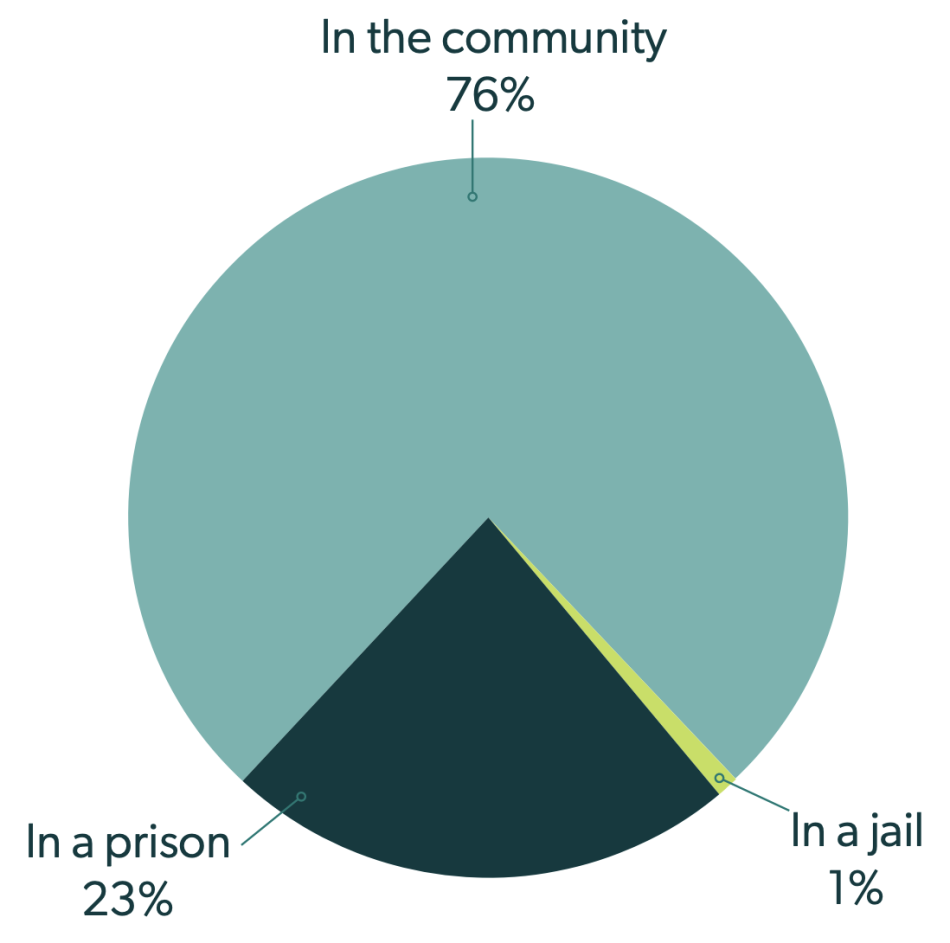

Disenfranchised Americans by Location, 2022 4.6 Million Banned from the Ballot Box

Source: Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022). Locked out 2022: Estimates of people denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

The majority of Americans who cannot vote due to a felony conviction – three out of every four – are living in our communities completing felony probation or parole.8 These individuals are working and paying taxes. They are caregivers. They raise children. Yet, because they cannot vote, they do not have a voice in everyday laws and policies that affect their lives. Excluding people from participating in democratic life is an additional punishment.9 Civic engagement, including the right to vote, plays an important role in successful reintegration.10

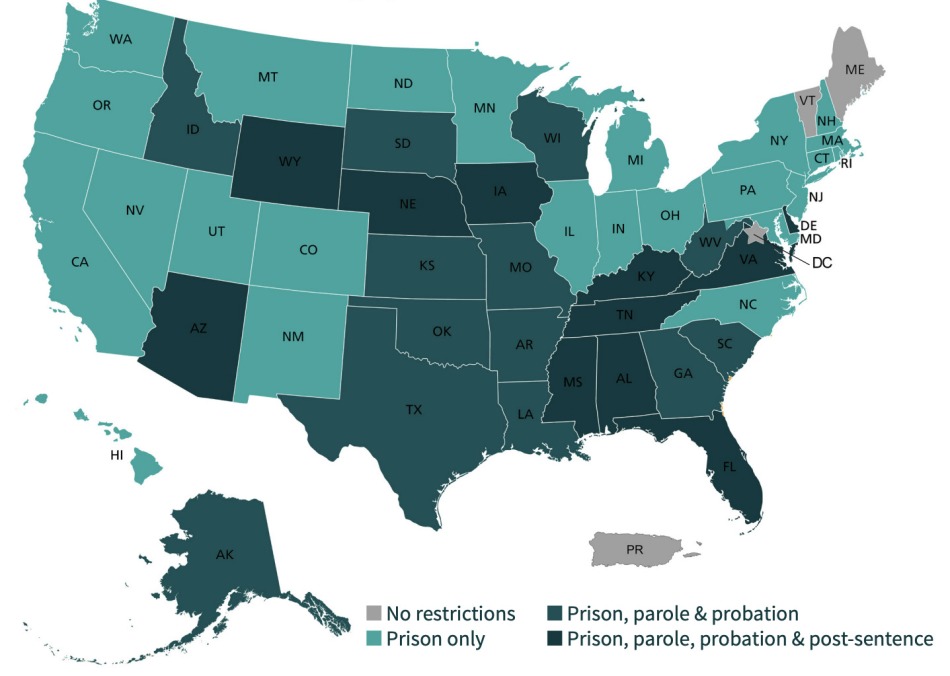

Felony disenfranchisement is particularly devastating for people of color, who are disproportionately represented in the criminal legal system.11 Over two million voting-eligible Black and Latinx Americans are blocked from participating in this fundamental right.12 In 2022, one in 19 voting-eligible Black Americans was banned from the ballot box. One in 10 Black Americans was banned from voting in Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Virginia.13 It is estimated at least 506,000 Latinx Americans are disenfranchised.14 Felony disenfranchisement perpetuates the racist intent behind its historical creation and acts as a contemporary structural barrier to advancing racial justice. Despite scientific evidence and public support15 for re-enfranchisement, having the right to vote is determined by geography in this country instead of our values as Americans due to variations in disenfranchisement laws and policies.

Voting Rights Restrictions in 2023

Source: Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022). Locked out 2022: Estimates of people denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. Modified and updated as of March 2023.

Promoting voting rights and public safety

Research finds that having the right to vote or the act of voting is related to increased public safety.

Voting as a public safety strategy

Retaining one’s voting rights regardless of involvement in the criminal legal system can be viewed as a public safety strategy. Two studies show associations between reduced recidivism and voting among people with a criminal history:

- Individuals who had their voting rights restored post-incarceration were found to have a lower likelihood of re-arrest compared to individuals in states which continued to restrict the right to vote after incarceration, according to a study conducted by Guy Padraic Hamilton-Smith, at JustLeadership USA, and Matt Vogel at the University of Albany.16 They analyzed three-year re-arrest rates in a nationally representative sample of 272,111 individuals released from prison in 15 states in 1994. After dividing states into two groups, permanent disenfranchisement or voting rights restoration post-release, they found that individuals were approximately 10% less likely to recidivate if they were released in automatic restoration states versus permanent disenfranchisement states.17 Hamilton-Smith and Vogel posit that felony disenfranchisement creates community reintegration barriers for justice-impacted individuals which becomes an additional contributor to future criminality.

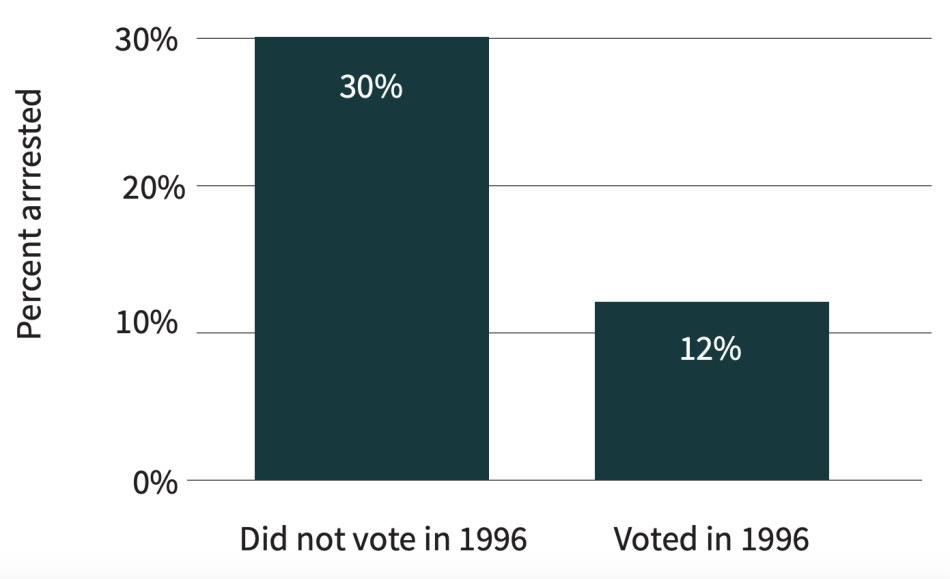

- Minnesotans with a criminal history were significantly less likely to be re-arrested if they voted in the 1996 presidential election, according to a study by Christopher Uggen at the University of Minnesota and Jeff Manza at New York University.18Uggen and Manza analyzed data from the Youth Development Study, a long-term study of a cohort of former Minnesota public school students. When analyzing the entire sample and controlling for prior unlawful behavior, like drunk driving, and background characteristics, like sex and race, respondents who voted in the 1996 presidential election had significantly lower odds of self reporting any involvement in property or violent crime during 1997-1998.19 Though there is no established causal order, meaning one cannot determine if voting leads to reduced involvement in crime, voting is associated with lower involvement in crime.Having the right to vote matters, and there is good reason to believe that voting is associated with a lower tendency to commit crime. The right to vote should be viewed as another prosocial reintegration strategy.

Percent Arrested in 1997-2000 with a Prior Criminal History

Comparing Voters and Non-Voters

Source: Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2004). Voting and subsequent crime and arrest: Evidence from a community sample. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 36(1), 193-216.

Voting as a community reintegration strategy

Studies show that having the right to vote shapes community re-entry experiences and is linked to intentions to remain crime-free.20 Restoration of voting rights also increases political efficacy, a sense that one’s voice can be heard in the political process.21

“I think that just getting back in the community and being a contributing member is difficult enough…[I] would like to someday feel like a, quote, ‘normal citizen,’ a contributing member of society, and you know that’s hard when every election you’re constantly being reminded, ‘Oh yeah, that’s right, I’m ashamed… It’s just loss after loss after loss.’”22

- In interviews with 33 people convicted of a felony, conducted as part of a larger research project by Christopher Uggen, Jeff Manza, and Angela Behrens, the right to vote was a fundamental component of developing a prosocial identity, whereas being restricted from voting reinforced an outsider status—feeling like a partial citizen. Interviewees also linked civic participation with intentions to remain crime free. Uggen and colleagues stress how civic reintegration contributes to forming identities as law-abiding citizens which aids in the desistance from crime.23

- Justice-impacted individuals felt that being banned from voting was “limiting, psychologically harmful, and stigmatizing,” according to Bryan Lee Miller, at Clemson University, and Joseph F. Spillane at the University of Florida.24 They conducted 54 in-depth interviews with disenfranchised citizens living in Florida to study their reintegration. Fifteen percent of the sample viewed the inability to vote as directly impeding their reintegration. Twenty-six percent viewed restrictions on voting as part of a package of obstacles to their integration, such as not being able to vote on issues that would improve their community or help create job opportunities. Thirty-nine percent of respondents directly connected their inability to vote to their perceived ability to remain law-abiding.25

- Restoration of voting rights improved respondents’ views that they could engage in the democratic process and feel their vote mattered, found Victoria Shineman at the University of Pittsburgh. She surveyed 98 Virginians with a felony conviction during the November 2017 gubernatorial election cycle who were eligible to vote or eligible to have their voting rights restored. She found that restoration increased justice-impacted individuals’ external political efficacy (e.g., one’s vote can make a difference) and internal political efficacy (e.g., confidence to participate in politics).21 Shineman explains that the extension of voting rights to justice-impacted individuals can lead to a sense of empowerment, confidence, and other prosocial attitudes that can increase reintegration success.

Voting is fundamental to expressing civic involvement and community belonging.27 It is shortsighted from a public safety perspective to continue to exclude millions of Americans from our democratic process.

Conviction-based voting rights exclusions do not advance public safety

Whether residing in the community or incarcerated, no justice-impacted American should be excluded from voting.28 It is part of our democratic process to have a voice in the laws and policies that govern our communities and nation. These democratic values are affirmed by the research showing voting’s beneficial effects on public safety and reintegration.

Yet, some states exclude people with certain conviction offenses, like murder and crimes of a sexual nature, from the right to vote. According to Paul Wright, a Florida native and Executive Director of the Human Rights Defense Center, “While some may point to the serious nature of their offenses, they have nothing to do with voting. The punishment of disenfranchisement does not fit the crime.”29 Instead, they have limited avenues for restoration, making restoration unlikely.14

Based on surveys of state law and policy conducted by the ACLU, the National Conference of State Legislatures, and The Sentencing Project, Table 1 lists states that carve out certain felony convictions from the typical restoration process. Most of these states require a governor’s pardon to restore voting rights for these convictions, such as in Florida, Iowa, Tennessee, and Wyoming. One state, Mississippi, also permits a two-thirds vote of both houses of the legislature in lieu of a governor’s pardon.

| State | State Carve Out Conviction Offense | Restoration Process |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Forty-six crimes of “moral turpitude,” such as homicide, rape, armed robbery, and drug trafficking | Homicide and crimes of a sexual nature are permanently disenfranchised, absent a gubernatorial pardon. Others require applying for a Certificate of Eligibility to Register to Vote. |

| Arizona | Two or more felony convictions | Potential restoration by a judge discharging at the end of the probation term, by petitioning the court, or by gubernatorial pardon. |

| Delaware | Murder, bribery, sexual offenses | Permanently disenfranchised, absent a gubernatorial pardon. |

| Florida | Murder, felony sexual offense | Permanently disenfranchised, absent a successful clemency petition to the Governor. |

| Iowa | Homicide offenses | Permanently disenfranchised, absent a gubernatorial pardon. |

| Kentucky | Treason, bribery in an election, violent felony offenses such as murder, manslaughter, homicide, sexual offenses, assault, strangulation, and human trafficking. Includes out-of-state and federal felony convictions. | Permanently disenfranchised, absent a gubernatorial pardon. |

| Mississippi | Twenty-two listed crimes such as murder, rape, bribery, theft, arson, obtaining money or goods under false pretense, perjury, forgery, embezzlement, and bigamy | Permanently disenfranchised, absent a gubernatorial pardon or a two-thirds vote of both houses of the legislature. |

| Tennessee | Murder, rape, treason, or voter fraud | Permanently disenfranchised, absent a gubernatorial pardon. |

| Wyoming | Felony convictions classified as violent and repeat non-violent felony convictions |

Permanently disenfranchised, absent a gubernatorial pardon. |

Sources: ACLU. (2023). Felony disenfranchisement laws (map); National Conference of State Legislatures. (2023). Felon voting rights; Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022). Locked out 2022: Estimates of people denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.; U.S. Department of Justice (2022). Guide to state voting rules that apply after a criminal conviction.

Delaware illustrates the onerous nature of re-enfranchisement for excluded conviction offenses. Individuals who are convicted of an eligible re-enfranchisement offense automatically have their right to vote restored after they complete their full sentence including parole, probation, and community supervision. But for individuals who are convicted of an excluded conviction offense, the state requires a pardon from the Governor. Some of the required steps for a pardon application include:31

- Submitting certified copies of (a) criminal history, which requires a fee and fingerprints; (b) all court dockets and sentencing orders and/or disposition records for all adult dispositions and any juvenile dispositions resulting in a conviction in an adult court; and (c) financial information on outstanding fines, costs, fees, and restitution.

- Undergoing a mental health exam by a licensed professional for qualifying conviction offenses, which includes acts causing death and crimes of a sexual nature.32

- Respondents must disclose their highest level of education, known learning disabilities, history of mental health issues, history of substance/alcohol abuse, marital status, employment status, dependent status, current enrollment in school/vocational training, and involvement in community or charitable activities.

Evidence from several states shows that requiring gubernatorial pardons to restore voting rights is a nearly insurmountable obstacle.33 The practice of excluding certain conviction offenses from the usual restoration process is highly problematic and does not advance public safety. As illustrated by research conducted in Florida, banning people from voting makes them feel ostracized, is psychologically harmful, and has a negative impact on perceptions of being able to live crime-free.25 As a country that views the right to vote as fundamental to our democracy, we should pursue all avenues to promote public safety and successful reintegration.

Conclusion

Mass incarceration continues to leave a stain on American democracy. The dramatic growth of the U.S. prison population, as well as the population on community supervision, has resulted in millions of citizens losing their right to vote due to a felony conviction.

Some states are making strides toward inclusive citizenship by enacting reforms. In 2023, Minnesota and New Mexico restored the right to vote for over 57,000 justice-impacted persons who are on felony probation or parole.35 In 2020, Washington, DC, became the third jurisdiction in the continental United States where individuals incarcerated for a felony conviction can vote.36 While this is progress, felony disenfranchisement remains deeply entrenched in this country.

To promote public safety and enhance reintegration efforts, states should dismantle laws and policies that exclude justice-impacted people from participating in our democracy. Science supports the right to vote as part of a package of prosocial behaviors and links voting to increased public safety. Moreover, denying the right to vote to an entire class of citizens is undemocratic and impedes racial equity. The United States should promote full democratic participation regardless of contact with the criminal legal system.

| 1. | Bozick, R., Steele, J., Davis, L., & Turner, S. (2018). Does providing inmates with education improve postrelease outcomes? A meta analysis of correctional education programs in the United States. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 14, 389-428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-018-9334-6; Uggen, C., Manza, J., & Behrens, A. (2013). ‘Less than the average citizen’: Stigma, role transition and the civic reintegration of convicted felons. In S. Maruna & R. Immarigeon (Eds.), After crime and punishment (pp. 258-287). Willan. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781843924203; Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2004). Voting and subsequent crime and arrest: Evidence from a community sample. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 36(1), 193-216. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Hamilton-Smith, G. P., & Vogel, M. (2012). The violence of voicelessness: The impact of felony disenfranchisement on recidivism. Berkeley La Raza Law Journal, 22, 407-432. https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38Z66F; Uggen & Manza (2004), see note 1. |

| 3. | Miller, B., & Spillane, J. (2012). Civil death: An examination of ex-felon disenfranchisement and reintegration. Punishment & Society, 14, 402–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474512452513; Shineman, V. (2020). Restoring voting rights: Evidence that reversing felony disenfranchisement increases political efficacy. Policy Studies, 41(2-3), 131-150. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2019.1694655; Uggen et al. (2013), see note 1. |

| 4. | Muhitch, K., & Ghandnoosh, N. (2021). Expanding voting rights to all citizens. The Sentencing Project. |

| 5. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022). Locked out 2022: Estimates of people denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.; Decarceration responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as disenfranchisement law and policy change, influenced the decrease in the disenfranchisement rate compared to 2020 (5.17 million disenfranchised) and 2016 (6.1 million disenfranchised) estimates. |

| 6. | Nellis, A. (2023). Mass incarceration trends. The Sentencing Project. |

| 7. | ACLU. (2006). Out of step with the world: An analysis of felony disenfranchisement in the U.S. and other democracies. ACLU.;Uggen et al. (2022), see note 5. |

| 8. | Uggen, C., Manza, J., & Thompson, M. (2006). Citizenship, democracy, and the civic reintegration of criminal offenders. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 605(1), 281–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271620628689 |

| 9. | Miller, B. L., & Agnich, L. E. (2016). Unpaid debt to society: Exploring how ex-felons view restrictions on voting rights after the completion of their sentence. Contemporary Justice Review, 19(1), 69-85. https://doi.org/10.1080/10282580.2015.1101685; Uggen et al. (2013), see note 1. |

| 10. | Cossyleon, J. E., & Flores, E. O. (2020). “I really belong here:” Civic capacity-building among returning citizens. Sociological Forum, 35(3), 721-743. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12625; Maruna, S. (2001). Making good: How ex-convicts reform and rebuild their lives. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10430-000; Miller & Spillane (2012), see note 3.; Smith, J. M. (2021). The formerly incarcerated, advocacy, activism, and community reintegration. Contemporary Justice Review, 24(1), 43-63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10282580.2020.1755846.; Uggen et al. (2013), see note 1. |

| 11. | Nellis, A. (2021). The color of justice: Racial and ethnic disparity in state prisons. The Sentencing Project. |

| 12. | Ghandnoosh, N. (2015). Black lives matter: Eliminating racial inequality in the criminal justice system. The Sentencing Project.; Nellis, A. (2023), see note 6.; Uggen et al. (2022), see note 5. |

| 13. | Uggen et al. (2022), see note 5. |

| 14. | Uggen et al. (2022), see note 5. |

| 15. | Lake Research Partners. (2022). New national poll shows majority favor guaranteed right to vote for all. Common Cause, The Sentencing Project, Stand Up America, and State Innovation Exchange. |

| 16. | Hamilton-Smith & Vogel (2012), see note 2. |

| 17. | Their analysis controlled for individual characteristics and |

| 18. | Uggen & Manza (2004), see note 1. Minnesotans without a criminal history were also significantly less likely to be arrested if they voted in the 1996 presidential election. |

| 19. | Property crimes were defined as shoplifting, theft, check forgery, or burglary. Violent crimes were defined as hitting or threatening to hit someone, fighting, or robbing someone. |

| 20. | Miller & Spillane (2012), see note 3. Uggen et al. (2013), see note 1. |

| 21. | Shineman, V. (2020), see note 3. |

| 22. | Uggen et al. (2013), see note 1, p. 275. |

| 23. | Uggen et al. (2013), see note 1. |

| 24. | Miller & Spillane (2012), see note 3, p. 423. |

| 25. | Miller & Spillane (2012), see note 3. |

| 26. | Shineman, V. (2020), see note 3. |

| 27. | Rahn, W. M., Brehm, J., & Carlson, N. (1999). National elections as institutions for building social capital. In M. Fiorina & T. Skocpol (Eds.), Civic engagement in American democracy (pp. 111-160). Brookings Institution and Russell Sage. |

| 28. | Muhitch & Ghandnoosh, see note 4. |

| 29. | Wright, P. (2018). The case against Amendment 4 on felon voting rights. Tallahassee Democrat. https://www.tallahassee.com/story/opinion/2018/09/19/case-against-amendment-4-felon-voting-rights-opinion/1351689002/ |

| 30. | Uggen et al. (2022), see note 5. |

| 31. | Delaware Board of Pardons. (2023). Delaware Board of Pardons checklist. https://pardons.delaware.gov/wpcontent/uploads/sites/42/2023/03/Pardon_Checklist_2023.pdf; Delaware Board of Pardons. (2023). Delaware Board of Pardons application packet. https://pardons.delaware.gov/wpcontent/uploads/sites/42/2023/03/Pardon_ApplicationPacket_2023.pdf |

| 32. | Mental Health Examinations Required by 11 Delaware Code § 4362. https://pardons.delaware.gov/psychiatricpsychological-examinations/ |

| 33. | Barrish, C., & Starkey, J. (2015). Dramatic rise in pardons in Delaware. Delaware Online. https://www.delawareonline.com/story/news/local/2015/04/25/dramatic-rise-pardonsdelaware/26374339/; Uggen et al. (2022), see note 5. |

| 34. | Miller & Spillane (2012), see note 3. |

| 35. | Deng, G. (2023, March 03). Walz signs bill giving people still on parole or probation right to vote. Minnesota Reformer. https://minnesotareformer.com/briefs/walz-signs-bill-giving-people-still-on-parole-or-probation-right-to-vote/; McKay, D. (2023, March 30). New Mexico has a sweeping new election law. Here are 6 key provisions in the bill. Albuquerque Journal. https://www.abqjournal.com/2586563/new-mexico-has-asweeping-new-election-law-here-are-6-key-provisions-inthe-bill.html; Minnesota restored the right to vote for over 46,000 Minnesotans who are on felony probation or parole. New Mexico restored the right to vote for over 11,000 New Mexicans who are on felony probation or parole. |

| 36. | Restore the Vote Amendment Act of 2020, D.C. Law 23-277 (2020). https://code.dccouncil.gov/us/dc/council/laws/23-277 |

state-level characteristics (felony disenfranchisement and the unemployment rate).