Responding to Crimes of a Sexual Nature: What We Really Want Is No More Victims

Report examines misconceptions around crimes of a sexual nature that contribute to the rise in imprisonment rates and the lengthening of sentences, and offers recommendations for reform.

Related to: Sentencing Reform, Incarceration, Racial Justice

- Introduction

- Misconceptions about Crimes of a Sexual Nature

- Research on CSN recidivism

- The Expansive System of Punishment for Crimes of a Sexual Nature

- Characteristics of People in State Prison Convicted of Sexual Offenses

- Increasing Punishment for People Convicted of Sexual Offenses

- State Laws and the Extent of Punishment

- New Approaches to CSN and Recommendations for Reform

- Appendix I. Methods

Introduction

Sexual violence in America remains a systemic social problem but excessive prison sentences do not address the root causes nor do they necessarily repair harm or bolster accountability. The misdirection of resources toward extreme punishment does little to prevent sexual violence.1

“What we really want is no more victims…So, how can we get there? Locking them up forever, labeling them, and not allowing them community support doesn’t work.Patty Wetterling, Co-Founder of the Jacob Wetterling Resource Center2

Since the 1990s, individuals convicted of sex crimes or sex offenses, which we call crimes of a sexual nature (CSN), have been subjected to an increased use of incarceration and longer sentences.3 They on average serve a greater percentage of their prison sentence compared to those sentenced for other crimes classified as violent, such as murder.4 The first federal law was also passed establishing state sex offense registries in 1994, the Jacob Wetterling Act.5

This escalation in punishment severity and community surveillance occurred alongside two opposing long-term trends. First, recidivism rates for CSN in the United States have declined by roughly 45% since the 1970s.6 This drop started well before the implementation of public registration and notification, implying that the lifelong punishment approach was not responsible for this decline. Second, based on roughly three decades of nationally representative U.S. criminal victimization data (1993-2021), the number of rape and sexual assault victimizations decreased by approximately 65%.7 Yet, reactions to CSN continue to evoke failed policies of the past – statutorily increasing minimum and maximum sentences and requiring more time served before release – major contributors to mass incarceration.8

This brief uses the term “crimes of a sexual nature” (CSN) to describe what are legally defined as “sex crimes” or “sex offenses.” While we do use similar terms interchangeably in this brief, The Sentencing Project recommends the use of “crimes of a sexual nature” to minimize labeling effects and potential cognitive bias.

Patty Wetterling, who once lobbied for sex offense registration after the abduction of her son, is now a vocal critic of it and many other sex crime laws. She reminds us that flawed laws and policies should be challenged, revisited, and changed. With this backdrop, this brief highlights misconceptions around crimes of a sexual nature that contribute to the rise in imprisonment and lengthening of sentences.9 It provides a set of recommendations including the following:

- Rely on established evidence about CSN and those who commit it to inform policy responses rather than fear-driven misinformation.

- Prioritize investments in prevention and intervention programming that works to reduce CSN and treat the underlying causes of CSN.

- End mandatory prison sentences for CSN convictions, including mandatory minimums and two- and three-strike laws. This category of crime includes a broad range of criminalized behavior such as consensual sex between youth to forcible rape. Each of these behaviors carries with it varying levels of criminal culpability. Sanctions should not be “one size fits all.”

- Resist the impulse to leverage CSN as a bargaining tool in order to pass sentencing reforms.

Misconceptions about Crimes of a Sexual Nature

In the fall of 2022, Scott* left prison after being incarcerated for more than 40 years for rape, an offense he committed as a young teenager. His decades in prison were devoted to intensive programming and cognitive behavioral therapy to understand the role his traumatic history played in his impulsive decision to commit this crime. Released as a result of Maryland’s Juvenile Restoration Act of 2021, Scott has dedicated his new freedom to assisting other returning individuals with the challenges of reentry after long-term incarceration for crimes of a sexual nature.

Unrecognized Histories of Trauma

Because of the nature of sexually-based offenses, individuals who are convicted of these offenses are too often denied their humanity. What is unrecognized is the trauma histories of individuals who have perpetrated CSN and how those trauma histories influence behavior.10 While not an excuse for CSN perpetration, these elevated to severe trauma-histories provide much needed context which is often missing from public discussions and proposed solutions to CSN. Individuals who have perpetrated CSN report substantially higher levels of childhood trauma – physical, verbal, and sexual abuse and emotional and physical neglect – compared to the general population.11 Measured by using the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) questionnaire,12 many women and men convicted of CSN have been found to have cumulative ACE scores that place them in the highly traumatized category.13 This history of childhood trauma extends to the youth population as well.14

Low Rates of Recidivism

Arguably one of the most ubiquitous and influential misconceptions is the alleged exceptionally high CSN recidivism rate.15 The common assumption is that people who commit sexually-based offenses are bound to commit them in the future. This fallacy has even been incorporated in US Supreme Court decisions, McKune v. Lile (2002) and Smith v. Doe (2003). In McKune v. Lile (2002) Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote, “of untreated [CSN] offenders [the recidivism rate] has been estimated to be as high as 80%…a frightening and high risk of recidivism.”16 The “frightening and high” language was then quoted the following year in Smith v. Doe (2003) which upheld Alaska’s public sex offense registry.17 It traces back to an unfounded claim in Psychology Today and has since been used in hundreds of judicial opinions and briefs.18

This ubiquitous phrase, “frightening and high,” continues to be used to justify long prison sentences, civil commitment, registration and notification, residence restrictions, and other mechanisms to address sexual recidivism.19 As detailed below, sexual recidivism rates are low. When individuals with this conviction do reoffend, it is typically with a non-CSN.20

Research on CSN recidivism

Criminologists have consistently found that criminal behavior is associated with age.21 Individuals are more likely to become involved in criminal behavior in their youth, but as they age into adulthood the proclivity toward criminal behavior drastically declines. While CSN does not exactly mirror the traditional age-crime curve due to different trends in onset and desistance, there is evidence of an “age-crime curve effect.”22

During the nine year follow-up, over 92% of individuals released with rape/sexual assault convictions were not rearrested for another rape or sexual assault.

Researchers at the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) tracked over 400,000 people originally convicted of rape or sexual assault who exited prison in 2005. During the nine year follow-up, over 92% of individuals released with rape/sexual assault convictions were not rearrested for another rape or sexual assault. Compared to individuals released for a non-CSN conviction, they were also less likely to be arrested post-release for any crime.23 Given the excessive obstacles individuals convicted of a CSN offense face in their communities upon release, it should not be surprising to see some level of recidivism.24 Such obstacles, like public registration and notification and residence restrictions, remain law although research consistently shows their failure to impact sexual recidivism.25

Moreover, recidivism risk decreases the longer individuals with a sex crime conviction are sex offense-free in the community.26 Researchers find that within 10 to 15 years of living sex offense-free in the community, the vast majority of individuals will be no more likely to commit a sex crime than individuals who have never been convicted of CSN.27 This finding even extends to those deemed “high risk” to sexually reoffend – high risk does not mean high risk forever.28 These studies align with criminological research on non-CSN offenses and reinforce that desistance is the norm.

| Post-Release Offense | Percent of Released Individuals Arrested |

|---|---|

| Public order | 58.9% |

| Property | 24.2% |

| Assault (simple or aggravated) | 18.7% |

| Drug | 18.5% |

| Rape or sexual assault | 7.7% |

| Robbery | 3.8% |

| Homicide | 0.2% |

Source: Alper, M., & Durose, M. R. (2019). Recidivism of sex offenders released from state prison: A 9-year follow-up (2005-2014). Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Relationship Dynamics

Another misconception is that crimes of a sexual nature are more likely to be perpetrated by a stranger, but evidence reveals that this is rarely the case. In a Bureau of Justice Statistics report tracking arrests for sexual assault in 20 states, 87% to 96% of people arrested for a CSN were known by the survivor.29 The stranger misconception influences public support for policies – like public registration and notification and residence restrictions – that do not address more common scenarios in which sexual victimization occurs, such as between intimate partners, family members, friends, and acquaintances.30

The misinformation surrounding CSN has translated into classifying individuals who commit CSN as unique and separate from individuals who commit other crime-types. As a result, increasingly punitive sentencing laws have been implemented across the United States over time, contributed to mass incarceration, and yet done little to address the underlying roots of sexual violence.

The Expansive System of Punishment for Crimes of a Sexual Nature

The United States is unique in its harsh punishments for crimes of a sexual nature (CSN) and its use of community supervision and exclusion mechanisms to attempt to prevent sexual recidivism.31 This includes long prison sentences, up to one’s natural life, civil commitment (indefinite confinement), chemical or surgical castration, requirements to register personal information on a publicly available website, community notification, limits where one can live (residence restrictions), and limits where one can go (e.g., child safety zones).

Given the extensive ramifications that result from a sex crime conviction, there is arguably an overbreadth of conduct that is classified as a sexually-based offense. Generally, there is a global understanding that the crime of rape is illegal and should be punished. Yet, criminalized conduct ranges across a broad spectrum of culpability including public nudity, indecent exposure (“flashing”), public urination, “sexting,” sex between consenting minors (statutory rape), soliciting sex workers, illegal image creation (e.g., a minor taking a nude photo of themselves), illegal image sharing (e.g., a minor sharing a nude photo of themselves), the creation or dissemination of sexually explicit images of youth, incest, to acts of fondling, sodomy, and rape using force.

While there is variation among states about which behaviors qualify as a CSN, all states and the federal system are too severe in their responses. For example, two consenting teenagers who have sex could receive up to a 15 year prison sentence in Florida or up to a 20 year prison sentence in Alabama due to statutory rape and other laws. These convictions could also trigger a lifetime public registration requirement.32 Such laws fail to advance community safety.33 Regardless of jurisdictional authority, CSN laws have expanded in scope and over time.34

Characteristics of People in State Prison Convicted of Sexual Offenses

Recent national statistics show that 15.5% of the prison population has been sentenced to prison for a rape or sexual assault.35 While the vast majority of individuals incarcerated for rape or sexual assault were men (99%), 2,200 women were incarcerated for these crime types.36

Racial Disparities

The rate of Black, Latinx, and American Indian and Alaskan Native individuals serving a sentence in state prison for rape or sexual assault was two to three times as high as white individuals.37 While Black Americans represent a small share of the general population (14%), the rate at which they are imprisoned for CSN is the highest of all groups. Of those serving a sentence for rape or sexual assault at year end 2020, 40% were white, 22% were Latinx, and 21% were Black.38

| Race or Ethnicity | Rate per 100,000 |

|---|---|

| Black | 74.3 |

| Latinx | 57.5 |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 53.4 |

| White | 25.5 |

| Asian | 10.9 |

Source: US Census Bureau. US Census: Quick Facts 2020; Carson, E. A. (2022). Prisoners in 2021 – Statistical Tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics.

For context, roughly 70% of all arrestees for rape and other sex offenses in 2020 were white.39 Evidence shows generally there are cumulative disadvantages for people of color throughout the stages of the criminal legal process, which leads to higher levels of incarceration.40 Moreover, punitive sentencing laws are influenced by racial perceptions of who commits crime.41 For example, white Americans who associate crime with people of color are more likely to support severe sentencing laws.42 The media then play a role by reinforcing stereotypical narratives that sexual assault is more likely to be perpetrated by Black men which is not supported by evidence.43 Historically, Black men were also severely punished for allegedly raping white women to combat consensual interracial sexual relationships during the reconstruction and post-reconstruction eras.44 These historical and contemporary intersections of racial social control play a role today in the disproportionate sanctioning of people of color for sexually-based offenses.

Increasing Punishment for People Convicted of Sexual Offenses

Compared to a decade ago, individuals convicted of rape or sexual assault are serving more time in prison prior to release. Based on our analysis, between 2010 and 2020, there was a 64% increase in the number of individuals who were in prison for 10 years or more for a rape or sexual assault conviction prior to release. If this pattern persists over time, it will have a compounding effect on the size of the prison population, contributing to mass incarceration, as well as slowing decarceration.45 While the data do not allow us to disentangle offense type beyond the general categories of rape and sexual assault, punishment for behaviors classified as CSN – such as consensual sex involving one or more minors who are close in age – can result in a prison sentence spanning one or more decades.

The statute doesn’t say impose the highest possible penalty…the statute says…impose a sentence that is ‘sufficient but not greater than necessary to promote the purposes of punishment.Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson46

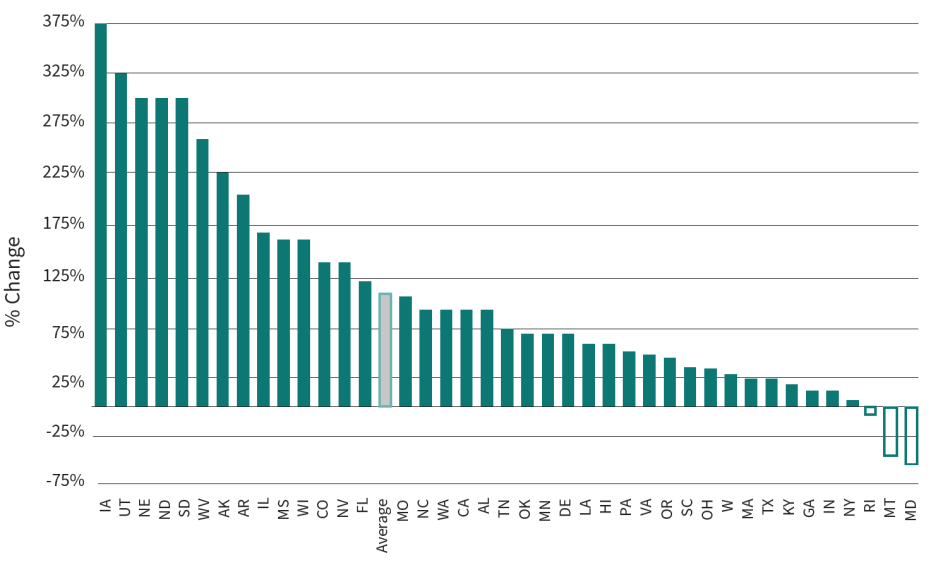

Though all states over punish some sexually-based offenses, there is variation across states in terms of the extent to which individuals are serving more time behind bars before release (see Figure 1). Iowa, Utah, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota saw at least a 300% increase in the number of individuals serving 10 or more years prior to release over this ten year period.47

There has also been a notable increase in the maximum number of years a person could serve in prison for a CSN conviction. Since 2010, on average, there has been a 31% increase in the proportion of the CSN prison population whose maximum sentence length was at least 25 years.48 For individuals who remained incarcerated at the end of 2020, more than 40% were sentenced to a maximum of at least 25 years.49

High maximum sentences such as these continue to contribute to the problem of mass incarceration because of resistance – both public and political – to release individuals from prison who have a CSN conviction. Evidence shows, after controlling for the amount of time a person has already spent in prison, that individuals seeking parole who were convicted of a sex offense have lower odds of being granted parole compared to individuals convicted of non-sex offenses such as robbery, theft, and burglary.50

| Time Served in 2020 | % Change in Time Served from 2010 |

|---|---|

| < 1 year | -45% |

| 1-1.9 years | -12% |

| 2-4.9 years | -11% |

| 5-9.9 years | 10% |

| 10+ years | 64% |

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics. National Corrections Reporting Program, 1991-2020: Selected Variables (Prison Releases, DS3). Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2022-11-28. Rape and sexual assault convictions only.

Life and Long-Term Sentences

As with other forms of lengthy sentences associated with the mass incarceration era, life sentences, which include life without parole (LWOP), life with parole (LWP), and virtual life (50 or more years), have grown over time.51 Based on The Sentencing Project’s 2020 national census of people serving life sentences, over 200,000 Americans are serving some form of life imprisonment.52 Approximately 19% of this population, over 38,000 people, have been convicted of a sexual offense. Since The Sentencing Project’s 2016 census, this population grew by almost 3,000 people over the course of four years.

Figure 1. Change in Prison Population Serving 10+ Years Prior to Release for a Rape or Sexual Assault Conviction by State, 2020 vs. 2010

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics. National Corrections Reporting Program, 1991-2020: Selected Variables (Prison Releases, DS3). Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2022-11-28.

Life sentences for crimes of a sexual nature are more common in certain states. Colorado (48%), Utah (54%), and Washington (69%) have some of the highest proportions of CSN lifers in their life-sentenced population. Driving these figures are sentencing laws requiring high mandatory minimum sentences up to natural life as well as habitual offender laws requiring a life sentence after two or three “strikes.”

| Type of Life Sentence | Number of People with a CSN Convention | % of Total Life-Sentenced Population (All Conviction Types) |

|---|---|---|

| Life Without Parole | 5,179 | 9% |

| Life With Parole | 21,048 | 20% |

| Virtual Life (50+ Years) | 11,946 | 28% |

State Laws and the Extent of Punishment

Colorado, Utah, and Washington’s sentencing laws include mandatory minimums up to mandatory life sentences. Such punishments have proliferated across the country as states adopted laws in response to high-profile sexual offenses perpetrated against youth. While these sentencing laws may have been well-intended, to deter CSN against children, the punishment is a one-size fits all response. They do not reflect the science on recidivism nor treatment amenability. They may keep individuals incarcerated much longer than needed, because they are no longer a risk to community safety. They default to incarceration when community-based sanctions and interventions may be more appropriate in some instances. Moreover, the laws also assume a monolithic punitively-oriented criminal legal response is wanted by all survivors.53

Colorado

The “Colorado Sex Offender Lifetime Supervision Act of 1998” (SOLSA) requires indeterminate sentences for specific CSN conviction offenses.54 This means a person does not know their actual release date and could spend up to the maximum of their natural life in prison. In 2005, the first year of available data, 621 individuals were sentenced under SOLSA. By 2022, the SOLSA CSN population more than doubled (over 1,600 individuals) – which is more than 2.5 times the size of the 2005 sentenced population.55

Utah

Utah passed a version of Jessica’s Law in 2008.56 It stipulates a mandatory prison term of 25 years to life without parole for certain CSN offenses committed against youth. It also removes the “authority” of the judiciary to impose a lesser sentence than the minimum term for those specific offenses. The Jessica Lunsford Act, referred to as Jessica’s Law, originated in Florida and has since spread to most states in one form or another.57

Washington

Washington’s Persistent Offender Accountability Act is a two and three “strike” law.58 If an individual is classified as a “persistent offender,” it is a mandatory term of life in prison without the possibility of parole 59 The law includes convictions in and outside the state of Washington. Washington also has a law similar to Jessica’s Law – House Bill 3277 – which triggers a mandatory minimum sentence of 25 years up to one’s natural life for specified offenses.60

Reflecting on Supreme Court Justice Jackson’s confirmation hearing, and her response to the allegation of leniency in her sentencing of individuals convicted of a sex crime, we can see the undue harshness of CSN sentences permitted by law. It is not surprising that some judges may use their discretion to deviate to a lesser but still punitive punishment. She rightly pointed out that the law does not require sentencing individuals to the extreme end of punishment. Yet, as we illustrate here, that is the direction we continue to move.

New Approaches to CSN and Recommendations for Reform

The United States cannot eradicate the perpetration of crimes of a sexual nature by continuously increasing sanctions. Yet, we continue to move in the wrong direction. In May 2023, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis revived the death penalty for the non-homicide offense of capital sexual battery effective October 2023.61 Such extreme sanctions are inhumane, exceptionally expensive, unconstitutional, and a misallocation of resources that could instead be used to truly address the root causes of sexual violence in America.

Ending mass incarceration requires us to look at our criminal legal approaches and responses to all crime types, including CSN. Our responses should be scientifically-driven by the multiple decades of research about CSN. CSN penalties should be reformed to still hold individuals accountable, while also advancing public safety, reflecting research, and accounting for mitigating factors and individual’s capacity for change. The Sentencing Project therefore recommends the following in relation to crimes of a sexual nature:

1. Cap CSN sentences at 20 years.

There is growing momentum for shortening prison terms as doubts about high rates of incarceration mount, but reforms often exclude those convicted of crimes of a sexual nature. The Sentencing Project advocates for reform approaches that include all conviction types. We recommend capping all sentences at 20 years regardless of conviction. Two decades in prison is an exceptionally long time. While The Sentencing Project provides an avenue to address the most extreme outlier cases that may call for additional incapacitation, we view it as a highly limited avenue which must include robust due process rights.62 Moreover, the elevated childhood trauma-history of people convicted of CSN can help inform appropriate criminal legal responses, such as using the ACE questionnaire as part of a pre-sentencing report to inform recommendations.

2. Reallocate money saved from lengthy and lifetime CSN sentences to invest in sexual violence prevention efforts and to provide support and assistance for survivors.

To support prevention efforts: Sexual violence is a public health issue, which calls for diversifying and increasing funding to make CSN prevention a priority.63 Implement prevention-oriented child sexual abuse programs, such as Erin’s Law.64 Make widely available evidence-based in-person training to prevent sexual violence, such as bystander intervention training.65 Given the high prevalence of ACEs among this population, reallocating fiscal resources to services for at-risk children and families would be one step aimed at breaking such cycles of violence.66

To support survivors: Provide robust therapeutic resources and treatment options at no cost, provide reimbursement for all out-of-pocket medical expenses, and provide advocacy and legal expertise, if desired, at no cost. Additionally, eliminate bureaucratic barriers to victim assistance funds in recognition of the adverse economic effects of CSN over the life course.67 Ensure such services are coordinated to alleviate any potential strain on survivors. The use of such resources should not be predicated on the survivor’s level of cooperation with law enforcement.

We should no longer “spare-no-expense” for extreme punishment that does little to deter nor address the root causes of sexual violence in our culture. The use of tax dollars and state and federal budgets on lengthy stays of CSN incarceration and incapacitation, estimated to be at minimum approximately $5.4 billion dollars annually, should be reinvested in prevention and survivor support systems.68

3. Use a holistic prosocial approach to reintegration when individuals with a CSN conviction offense transition from incarceration to the community.

Restorative justice practices and evidence-based, pro-social community-based management strategies can help to provide social support when individuals with a CSN conviction offense transition from incarceration to the community. They face an environment that produces considerable strain during the reentry process and thereafter, in part due to CSN misconceptions and inflammatory rhetoric about this offense type.69 Individuals convicted of CSN, particularly if they are required to be on a public registry, experience what has been called a social death.70 Housing instability and homelessness is a chronic problem and has been highlighted in states like Florida, California, Oregon, and South Carolina.71 Employment barriers are particularly acute.72 Social death also extends to civic exclusion – the loss of voting rights and in some states for life.73 These are known or related factors that have been shown to suppress crime, bolster reintegration, and contribute to desistance from CSN offending.74

4. Improve overall news media coverage to accurately portray CSN.

The Sentencing Project’s media guide can be a valued asset to all newsrooms who report on CSN.75 At a minimum, reporters should use neutral first-person language, avoiding stigmatizing terms, because it is less pejorative. We are talking about people. Research shows that labeling triggers stereotypes and misconceptions of individuals involved in incidents of CSN.76A review of a decade of research on the relationship between policy, media, and perceptions of CSN concluded that “there is a clear cyclical relationship.” Media coverage perpetuates CSN misconceptions. Public perceptions of these misconceptions influence law and policy. Lawmakers perceive that the public supports harsher punishments as the media cover “the most heinous crimes.” This continues to serve as a justification for “severe, long-term punishments.”77 Responsible media reporting on CSN is imperative given its role in shaping public perceptions of crime and punishment.42

Appendix I. Methods

This analysis used two sources: publicly available data collected by the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ (BJS) National Corrections Report Program (NCRP) and The Sentencing Project’s national census of the life-sentenced population.

The NCRP data analysis: The NCRP 1991-2020 (ICPSR 38492) was used in two separate analyses. They only included the most serious sentenced offense of “rape/sexual assault.” For comparison purposes, states were included if they reported data for both 2010 and 2020. The time served analysis used the DS3 Prison Releases file. To compare 2010 to 2020 figures, we calculated a rate of change over time for each of the time served categories provided in the NCRP: <1 year, 1-1.9 years, 2-4.9 years, 5-9.9 years, and ≥10 years. The maximum sentence length analysis used the DS4 Year-end Population file. The NCRP provides seven maximum sentence length categories. From that data, we condensed these to three categories: <10 years, ≥10 years to <25 years, and ≥25 years (including life sentences). To compare 2010 to 2020 figures, we calculated a rate of change over time for the three maximum sentence length categories.

The life-sentenced data analysis. Using The Sentencing Project’s 2020 national census of the life-sentenced population, we totaled the count of individuals serving a life-sentence for a CSN conviction for each of the following categories: life without parole, life with parole, and virtual life (50+ years). Data were obtained directly from state departments of corrections. For each category, we then calculated the proportion of individuals serving a life-sentence for a CSN conviction from the total life-sentenced population (regardless of conviction offense). We then used the 2016 census to calculate the change in the number of people serving a life sentence for a CSN conviction from 2016 to 2020.

| 1. | Janus, E. S. (2020). Preventing sexual violence: Alternatives to worrying about recidivism. Marquette Law Review, 103, 819-845.; Petrich, D. M., Pratt, T. C., Jonson, C. L., & Cullen, F. T. (2021). Custodial sanctions and reoffending: A meta analytic review. Crime and Justice: A Review of the Research, 50, 1-72. https://doi.org/10.1086/715100 |

|---|---|

| 2. | The Jacob Wetterling Resource Center was founded in 1990 to educate and assist families and communities to address and prevent the exploitation of children.; Baran, M., & Vogel, J. (2016, October 4). Sex offender registries: How the Wetterling abduction changed the country. AMP Reports. https://www.apmreports.org/story/2016/10/04/sex-offender-registries-wetterling-abduction?utm_content=HTML |

| 3. | Alper, M., & Durose, M. R. (2019). Recidivism of sex offenders released from state prison: A 9-year follow-up (2005-2014). Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/rsorsp9yfu0514.pdf; Cochran, J., Toman, E., Shields, R., & Mears, D. (2021). A uniquely punitive turn? Sex offenders and the persistence of punitive sanctioning. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 58(1), 74–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427820941172; Imprisonment for CSN also decreases the odds of being granted parole which contributes to longer stays. See, for example, Huebner, B. M., & Bynum, T. S. (2006). An analysis of parole decision making using a sample of sex offenders: A focal concerns perspective. Criminology, 44(4), 961-991. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2006.00069.x; Vîlcică, E. R. (2018). Revisiting parole decision making: Testing for the punitive hypothesis in a large U.S. jurisdiction. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(5), 1357-1383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X16668512 |

| 4. | Kaeble, D. (2021). Time served in state prison, 2018. Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/tssp18.pdf; Kaeble, D. (2018). Time served in state prison, 2016. Bureau of Justice |

| 5. | The Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Registration Act (1994) was enacted as part of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (see, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-103hr3355enr/pdf/BILLS-103hr3355enr.pdf). The 1994 Crime Bill also increased penalties for sexual offenses committed against youth. |

| 6. | It is important to note that the victims’ rights movement was pivotal during this time period in rape law reform (e.g., recognition and statutorily defining marital rape as a crime) as well as seeking accountability through the criminal legal system via increased use of incarceration and longer prison sentences for rape and sexual assault (see, for example, Leon, C. S. (2011). Sex offender punishment and the persistence of penal harm in the U.S. International Journal of Law & Psychiatry, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2011.04.004; Vitiello, M. (2023). The victims’ rights movement: What it gets rights, what it gets wrong. New York University Press.).; Lussier, P., McCuish, E., & Jeglic, E. (2023). Against all odds: The unexplained sexual recidivism drop in the United States and Canada. Crime and Justice, 52, 1-71. https://doi.org/10.1086/727028 |

| 7. | Bureau of Justice Statistics. National crime victimization survey (NCVS), 1993-2021. https://ncvs.bjs.ojp.gov/multi-year-trends/characteristic; In the NCVS, rape and sexual assault are combined to form one measure. The NCVS defines rape as the “unlawful penetration of a person against the will of the victim, with use or threatened use of force, or attempting such an act” whereas sexual assault “encompasses a wide range of victimizations” and includes “attacks or attempted attacks generally involving unwanted sexual contact between victim and offender, with or without force…grabbing or fondling and verbal threats.” See terms: https://ncvs.bjs.ojp.gov/terms; Finkelhor, D., & Jones, L. (2012). Have sexual abuse and physical abuse declined since the 1990s? Crimes Against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire. https://scholars.unh.edu/ccrc/61/ |

| 8. | National Research Council. (2014). The growth of incarceration in the United States: Exploring causes and consequences. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18613 |

| 9. | Cochran et al. (2021), see note 3.; Ellman, I. M., & Ellman, T. (2015). “Frightening and high”: The Supreme Court’s crucial mistake about sex crime statistics. Constitutional Commentary, 30, 495-508. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/concomm/419; Fox, K.J. (2013). Incurable sex offenders, lousy judges, & the media: Moral panic sustenance in the age of new media. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 38, 160-181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-012-9154-6; Koon-Magnin, S. (2015). Perceptions of and support for sex offender policies: Testing Levenson, Brannon, Fortney, and Baker’s findings. Journal of Criminal Justice, 43(1), 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2014.12.007; Quinn, J. F., Forsyth, C. J., & Mullen-Quinn, C. (2004). Societal reaction to sex offenders: A review of the origins and results of the myths surrounding their crimes and treatment amenability. Deviant Behavior, 25(3), 215-232. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639620490431147; Sample, L. L., & Kadleck, C. (2008). Sex offender laws: Legislators’ accounts of the need for policy. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 19(1), 40-62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403407308292 |

| 10. | Fox, B. H., Perez, N., Cass, E., Baglivio, M. T., & Epps, N. (2015). Trauma changes everything: Examining the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and serious, violent and chronic juvenile offenders. Child Abuse & Neglect, 46, 163-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.01.011 |

| 11. | Delisi, M., Kosloski, A. E., Vaughn, M. G., Caudill, J. W., & Trulson, C. R. (2014). Does childhood sexual abuse victimization translate into juvenile sexual offending? New evidence. Violence & Victims, 29, 620-635. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-13-00003; Jennings, W. G., Zgoba, K. M., Maschi, T., & Reingle, J. M.(2014). An empirical assessment of the overlap between sexual victimization and sex offending. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 58, 1466-1480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X13496544; Levenson, J. S., & Grady, M. D. (2016). The influence of childhood trauma on sexual violence and sexual deviance in adulthood. Traumatology, 22, 94-103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/trm0000067; Levenson, J. S., Willis, G. M., & Prescott, D. S. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences in the lives of female sex offenders. Sexual Abuse, 27, 258-283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063214544332; Neofytou, E. (2022). Childhood trauma history of female sex offenders: A systematic review. Sexologies, 31, 99-106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sexol.2021.10.003 |

| 12. | The ACE questionnaire consists of 10 items. Five items capture exposure to abuse (physical, verbal, or sexual) and neglect (physical and emotional). The other five items capture family factors which include substance abuse by parents, family violence, incarceration of family members, family members diagnosed with a mental illness or whom attempted suicide, and the disappearance of a parent through divorce, death, or abandonment. |

| 13. | Stensrud, R. H., Gilbride, D. D., & Bruinekool, R. M. (2019). The childhood to prison pipeline: Early childhood trauma as reported by a prison population. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 62(4), 195-208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034355218774844 |

| 14. | Budd, K. M. (2017). Female sexual offenders. In V. B. Van Hasselt & M. L. Bourke (Eds.), Handbook of Behavioral Criminology (pp. 297-311). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61625-4; Frey, L. L. (2010). The juvenile female sexual offender: Characteristics, treatment, and research. In T. A. Gannon & F. Cortoni (Eds.), Female sexual offenders: Theory, assessment, and treatment (pp. 53-70). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470666715; Jespersen, A. F., Lalumière, M. L., & Seto, M. C. (2009). Sexual abuse history among adult sex offenders and non-sex offenders: A meta analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 179-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.07.004. Seto, M., & Lalumiere, M. L. (2010). What is so special about male adolescent sexual offending? A review and test of explanations through meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 526-575. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0019700 |

| 15. | Sexual recidivism is typically measured as a subsequent arrest for another sex offense after having a prior sex crime conviction. Quinn et al. (2004), see note 9.; Zatkin, J., Sitney, M., & Kaufman, K. (2022). The relationship between policy, media, and perceptions of sexual offenders between 2007 and 2017: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(3), 953-968. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020985568 |

| 16. | We added the italicized text in the brackets for clarity purposes.; McKune v. Life, 536 U.S. 24, 33 (2002). https://www.oyez.org/cases/2001/00-1187 |

| 17. | Smith v. Doe, 538 U.S. 84 (2003). https://www.oyez.org/cases/2002/01-729 |

| 18. | Ellman & Ellman (2015), see note 9. |

| 19. | Ellman & Ellman (2015), see note 9. |

| 20. | Alper & Durose (2019), see note 3.; Przybylski, R. (2015). Recidivism of adult sexual offenders. Office of Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending, Registering, and Tracking. https://smart.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh231/files/media/document/recidivismofadultsexualoffenders.pdf |

| 21. | Loeber, R., & Farrington, D. (2014). Age-crime curve. In G. Bruinsma & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. (pp. 12-18). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5690-2; Neil, R., & Sampson, R. (2021). The birth lottery of history: Arrest over the life course of multiple cohorts coming of age, 1995–2018. American Journal of Sociology, 126(5), 1127–1178. https://doi.org/10.1086/714062 |

| 22. | Crookes, R. L., Tramontano, C., Brown, S. J., Walker, K., & Wright, H. (2022). Older individuals convicted of sexual offenses: A literature review. Sexual Abuse, 34(3), 341-371. https://doi.org/10.1177/10790632211024244 |

| 23. | Alper & Durose (2019), see note 3.; When rearrested, the crimes were more likely to be public order, property, assault (simple or aggravated), or a drug offense. |

| 24. | Ackerman, A. R., & Sacks, M. (2012). Can general strain theory be used to explain recidivism among registered sex offenders? Journal of Criminal Justice, 40, 187-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011.11.002; Hamilton, E., Sanchez, D., & Ferrara, M. L. (2022). Measuring collateral consequences among individuals registered for a sexual offense: Development of the sexual offender collateral consequences measure. Sexual Abuse, 34(3), 259–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/10790632211019733 |

| 25. | Socia, K. M. (2014). Residence restrictions are ineffective, inefficient, and inadequate: So now what? Criminology & Public Policy, 13, 179-188. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12071; Zgoba, K. M., & Mitchell, M. M. (2023). The effectiveness of sex offender registration and notification: A meta-analysis of 25 years of findings. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 19, 71–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-021-09480-z |

| 26. | Alper & Durose (2019), see note 3.; Farmer, M., McAlinden, A-M., & Maruna, S. (2015). Understanding desistance from sexual offending: A thematic review of research findings. Probation Journal, 62(4), 320-335. https://doi.org/10.1177/0264550515600545; Hanson, R. K., Harris, A. J. R., Helmus, L., & Thornton, D. (2014). High-risk sex offenders may not be high risk forever. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(15), 2792-2813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514526062; Hanson, R. K., Harris, A. J. R., Letourneau, E., & Helmus, L. M. (2018). Reductions in risk based on time offense-free in the community: Once a sexual offender, not always a sexual offender. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 24(1), 48-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/law0000135; Przybylski (2015), see note 20.; Worling, J. R., & Langton, C. M. (2022). Factors related to desistance from sexual recidivism. In C. M. Langton & J. R. Worling (Eds.), Facilitating desistance from aggression and crime: Theory, research, and strength-based practice (pp. 211-229). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119166504 |

| 27. | Hanson et al. (2018), see note 26.; The study population in this research was derived from previous studies used to develop and norm the Static-99R sexual offending risk tool (e.g., samples drawn from prison treatment, community treatment, corrections, community supervision). |

| 28. | Hanson et al. (2014), see note 26.; Hanson et al. (2018), see note 26. |

| 29. | Martin, K. H. (2021). Sexual assaults recorded by law enforcement, 2019. https://bjs.ojp.gov/nibrs/reports/sarble/sarble19; The BJS report includes the 20 states which had 100% of their state’s law enforcement data reported to the National Incident-Based Reporting System in 2019. |

| 30. | Martin (2021), see note 29.; Snyder, H. N. (2000). Sexual assault of young children as reported to law enforcement: Victim, incident, and offender characteristics. Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/sexual-assault-young-children-reportedlaw-enforcement-victim-incident-and; CDC. (2022). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey: 2016/2017 report on sexual violence. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs/nisvsReportonSexualViolence.pdf |

| 31. | Lussier et al. (2023), see note 6.; Petrunik, M. (2003). The hare and the tortoise: Dangerousness and sex offender policy in the United States and Canada. Canadian Journal of Criminology & Criminal Justice, 45, 43-72. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjccj.45.1.43; Petrunik, M., & Deutschmann, L. (2008). The exclusion–inclusion spectrum in state and community response to sex offenders in Anglo-American and European jurisdictions. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 52(5), 499-519. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X07308108 |

| 32. | Goodhue, D. (2019, February 6). FL Keys teen’s relationship turns criminal on his 18th birthday. Miami Herald. https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/florida-keys/article225560840.html; Florida Statute 800.04, Lewd or lascivious offenses committed upon or in the presence of persons less than 16 years of age. http://www.leg.state.fl.us/Statutes/index.cfm?App_mode=Display_Statute&Search_String=&URL=0800-0899/0800/Sections/0800.04.html; RAINN. (2023). Sex crimes: Definitions and penalties, Alabama. https://apps.rainn.org/policy/policy-crimedefinitions-export.cfm?state=Alabama&group=3 |

| 33. | Mancini, C., Barnes, J. C., & Mears, D. P. (2013). It varies from state to state: An examination of sex crime laws nationally. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 24(2), 166-198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403411424079 |

| 34. | Frank, D. J., Camp, B. J., & Boutcher, S. A. (2010). Worldwide trends in the criminal regulation of sex, 1945-2005. American Sociological Review, 75(6), 867-893. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122410388493 |

| 35. | At the end of the 2020 year, 161,500 people were in prison for rape or sexual assault. Carson, A. E. (2022). Prisoners in 2021 – Statistical tables. Table 16 and Table 17. Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/document/p21st.pdf |

| 36. | This gender breakdown is typical with criminal justice data due to reports to law enforcement, although victimization surveys find higher prevalence rates of women who have perpetrated CSN.; See, Cortoni, F., Babchishin, K. M., & Rat, C. (2017). The proportion of sexual offenders who are female is higher than thought: A metaanalysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 44(2), 145–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854816658923 |

| 37. | United States Census Bureau. (2020). Quick facts United States, population census, April 1, 2020. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/POP010220; In the 2020 census, white Americans made up approximately 76% of the population. |

| 38. | Carson (2022), see note 35; One percent were Alaska Native or American Indian and 1% were Asian. Approximately 14% of the race and ethnicity data were unknown. |

| 39. | The “other sex offense” category is defined as offenses against chastity, common decency, morals, and the like and excludes rape, prostitution, and commercialized vice.; FBI crime data explorer. Arrests offense counts in the United States, 2020. https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/arrest |

| 40. | Ghandnoosh, N. (2015). Black lives matter: Eliminating racial inequity in the criminal justice system. The Sentencing Project. |

| 41. | Ghandnoosh, N. (2014). Race and punishment: Racial perceptions of crime and support for punitive policies. The Sentencing Project. |

| 42. | Ghandnoosh (2014), see note 41. |

| 43. | Benedict, H. (1992). Virgin or vamp: How the press covers sex crimes. Oxford University Press. Duru, N. J. (2004). The Central Park Five, the Scottsboro Boys, and the myth of the bestial Black man. Cardozo Law Review, 25(4), 1315-1365. https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev/1551/; Ghandnoosh (2014), see note 41.; Patton, T. O., & Snyder-Yuly, J. (2007). Any four black men will do: Rape, race, and the ultimate scapegoat. Journal of Black Studies, 37(6), 859-895. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934706296025 |

| 44. | Donat, P. L. N., & D’Emilio, J. (1992). A feminist redefinition of rape and sexual assault: Historical foundations and change. Journal of Social Issues, 48(1), 9-22. |

| 45. | Ghandnoosh, N. (2023). Ending 50 years of mass incarceration: Urgent reform needed to protect future generations. The Sentencing Project.; Ghandnoosh, N., & Nellis, A. (2022). How many people are spending over a decade in prison? The Sentencing Project. |

| 46. | Kim, S. M., Davis, A. C., & Kane, P. (2022, March 22). Ketanji Brown Jackson passionately defends her sentencing of sex offenders. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/03/22/ketanji-brown-jackson-sex-offenders/; Quote from Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s confirmation hearing in regard to her sentencing record pertaining to the federal cases involving the crime of ‘child pornography.’ |

| 47. | No states saw a decrease in these long terms of incarceration with the exception of Rhode Island, Montana, and Maryland. |

| 48. | For comparison purposes, change over time (2010 to 2020) only included 40 states who reported data for both years. From 2010 to 2020, North Dakota, Alaska, Nebraska, Wyoming, West Virginia, Montana, Virginia, and California saw more than a 60% increase in the number of individuals in prison who were sentenced to a maximum prison term of 25 years or more. |

| 49. | All 46 states with available data were included in the 2020 statistic (>40%). States that did not report maximum sentence length data in 2020 include Arizona, Michigan, New Jersey, and New Mexico. |

| 50. | Huebner & Bynum (2006), see note 3. |

| 51. | Nellis, A. (2023). Mass incarceration trends. The Sentencing Project. |

| 52. | Nellis, A. (2021). No end in sight: America’s enduring reliance on life imprisonment. The Sentencing Project. |

| 53. | Burns, C. J., & Sinko, L. (2023). Restorative justice for survivors of sexual violence experienced in adulthood: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(2), 340-354. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211029408; McGylnn, C., & Westmarland, N. (2019). Kaleidoscopic justice: Sexual violence and victim-survivors’ perceptions of justice. Social & Legal Studies, 28(2), 179-201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663918761200 |

| 54. | Colorado Sex Offender Lifetime Supervision Act of 1998. House Bill 98-1156. https://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/images/olls/1998a_sl_303.pdf; These include sexual assault, felony unlawful sexual contact, sexual assault on a child, sexual assault on a child by one in a position of trust, Internet sexual exploitation of a child, aggravated sexual assault on a client by a psychotherapist, enticement of a child, Internet luring of a child, incest, aggravated incest, patronizing a prostituted child, trafficking in children, sexual exploitation of children, procurement of a child for sexual exploitation, soliciting for child prostitution, pandering of a child, procurement of a child, keeping a place of child prostitution, pimping of a child, or inducement of child prostitution. |

| 55. | Correspondence with Colorado’s Department of Corrections Office of Planning & Analysis (June 2023). The year 2005 was the first available year the counts were separated in the Department of Correction data to distinguish between the lifetime supervision and non-lifetime supervision populations. |

| 56. | H.B. 256, Ch. 179 (2008). Criminal penalties amendments – Including Jessica’s Law. https://le.utah.gov/~2008/bills/static/hb0256.html |

| 57. | Jessica Lunsford Act. H.B. 1877 (2005). https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2005/1877/BillText/er/PDF |

| 58. | Washington State Legislature. RCW 9.94A.570. Persistent offenders. Three-strike and two-strike provisions: RCW 9.94A.030(37)(a) and RCW 9.94A.030(37)(b). https://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=9.94A.570#:~:text=Notwithstanding%20the%20statutory%20maximum%20sentence,when%20authorized%20by%20*RCW%2010.95 |

| 59. | The law details which offense types will qualify an individual as a persistent offender. The two strikes law is limited to specific CSN offenses. The three strikes provision includes non-CSN felonious offenses. |

| 60. | H.B. 3277 (2006). Authorizing special verdicts for specified sex offenses against children and vulnerable adults. https://app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?BillNumber=3277&Year=2005 |

| 61. | Ray, S. (2023). DeSantis Signs New Death Penalty Bill—Setting Up Possible Supreme Court Clash. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/siladityaray/2023/05/02/desantis-signs-new-deathpenalty-legislation-sets-up-potential-clash-with-supremecourt/?sh=6b4445bb5843 |

| 62. | Komar, L., Nellis, A., & Budd, K. M. (2023). Counting down: Paths to a 20-year maximum prison sentence. The Sentencing Project. Nelson, M., Feineh, S., & Mapolski, M. (2023). A new paradigm for sentencing in the United States. Vera Institute of Justice. https://www.vera.org/publications/a-new-paradigm-for-sentencing-in-the-united-states |

| 63. | Waechter, R., & Ma, V. (2015). Sexual violence in America: Public funding and social priority. American Journal of Public Health, 105(12), 2430–2437. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302860 |

| 64. | Erin’s Law. https://www.erinslaw.org/; Erin’s Law requires that all public schools in each state implement a prevention-oriented child sexual abuse program which teaches: Students in grades pre-K – 12th grade, age-appropriate techniques to recognize child sexual abuse and tell a trusted adult; School personnel all about child sexual abuse; and Parents & guardians the warning signs of child sexual abuse, plus needed assistance, referral or resource information to support sexually abused children and their families. |

| 65. | Mujal, G. N., Taylor, M. E., Fry, J. L., Gochez-Kerr, T. H., & Weaver, N. L. (2021). A systematic review of bystander interventions for the prevention of sexual violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(2), 381–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019849587 |

| 66. | Budd (2017), see note 14.; Delisi et al. (2014), see note 11.; Frey (2010), see note 14.; Jennings et al. (2014), see note 11.; Jespersen et al. (2009), see note 14.; Levenson & Grady (2016), see note 11.; Levenson et al. (2015), see note 11.; Neofytou (2022), see note 11.; Seto & Lalumiere (2010), see note 14. |

| 67. | Loya, R. M. (2015). Rape as an economic crime: The impact of sexual violence on survivors’ employment and economic wellbeing. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(16), 2793–2813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514554291 |

| 68. | Letourneau, E. J., Roberts, T. W. M., Malone, L., & Sun, Y. (2022). No check we won’t write: A report on the high cost of sex offender incarceration. Sexual Abuse, 35(1), 54-82. https://doi.org/10.1177/10790632221078305; These estimates only apply to CSN involving youth; hence they underestimate financial expenditures spent on incarceration for CSN. These estimates include state prison (approximately $4.4 billion each year), federal prison (approximately $508 million each year), and civil commitment facilities (approximately $538 million each year). Adjusted for 2021 inflation rates. |

| 69. | Azoulay, N., Winder, B., Murphy, L., & Fedoroff, J. P. (2019). Circles of support and accountability (CoSA): A review of the development of CoSA and its international implementation. International Review of Psychiatry, 31(2), 195-205. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2018.1552406; Duwe, G. (2013). Can circles of support and accountability (COSA) work in the United States? Preliminary results from a randomized experiment in Minnesota. Sexual Abuse, 25(2), 143-165. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063212453942; McAlinden, A-M. (2022). Reconceptualizing ‘risk’: Towards a humanistic paradigm of sexual offending. Social & Legal Studies, 31(3), 389-408. https://doi.org/10.1177/09646639211032957 |

| 70. | See, for example, Megale, E. (2011). The invisible man: How the sex offender registry results in social death. Journal of Law and Social Deviance, 2, 9-15. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1938397 |

| 71. | Cann, D., & Isom Scott, D. A. (2020). Sex offender residence restrictions and homelessness: A critical look at South Carolina. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 31(8), 1119-1135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403419862334; Investigative staff (2023, June 05). Hundreds of Oregon sex offenders left homeless, unable to find housing. The Oregonian. https://www.oregonlive.com/news/2023/06/hundreds-of-oregon-sex-offenders-left-homeless-unable-to-find-housing.html; Levenson, J. S. (2018). Hidden challenges: Sex offenders legislated into homelessness. Journal of Social Work, 0(0), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017316654811; Yoder, S. (2023, March 21). As Florida’s unhoused sex offense registrant population booms, group asks UN for help. The Appeal. https://theappeal.org/south-florida-sex-offense-homelesspopulation-spikes/ |

| 72. | Brown, K., Spencer, J., & Deakin, J. (2007). The reintegration of sex offenders: Barriers and opportunities for employment. The Howard Journal, 46(1), 32-42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2311.2007.00452.x |

| 73. | Budd, K. M., and Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project. |

| 74. | Farmer et al. (2015), see note 26.; Worling & Langton (2022), see note 26. |

| 75. | Ghandnoosh, N. (2023). Media guide: 10 crime coverage dos and don’ts. The Sentencing Project. |

| 76. | Harris, A. J., & Socia, K. M. (2016). What’s in a name? Evaluating the effects of the “sex offender” label on public opinions and beliefs. Sexual Abuse, 28(7), 660–678. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063214564391; Lowe, G., & Willis, G. (2020). “Sex offender” versus “person”: The influence of labels on willingness to volunteer with people who have sexually abused. Sexual Abuse, 32(5), 591–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063219841904 |

| 77. | Zatkin et al. (2022), see note 15. |

| 78. | Ghandnoosh (2014), see note 41. |

Statistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/redirect-legacy/content/pub/pdf/tssp16.pdf