Youth Justice by the Numbers

Between 2000-2022, there has been a 75% decline in youth incarceration. However, racial and ethnic disparities in youth incarceration and sentencing persist despite overall decrease in youth offending.

Related to: Youth Justice

Between 2000-2022, there was a 75% decline in youth incarceration. However, racial and ethnic disparities in youth incarceration and sentencing persist amidst overall decrease in youth offending.

Introduction

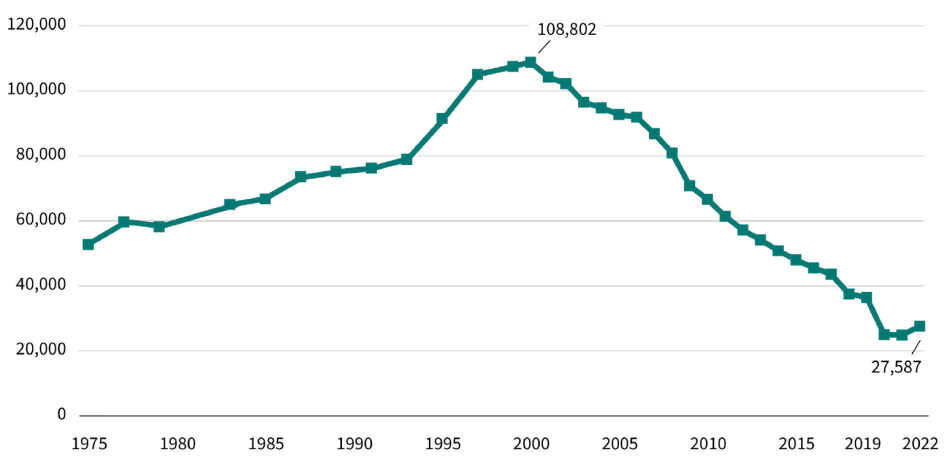

Youth arrests and incarceration increased in the closing decades of the 20th century but have fallen sharply since. Public opinion often lags behind these realities, wrongly assuming both that crime is perpetually increasing and that youth offending is routinely violent. In fact, youth offending is predominantly non-violent, and the 21st century has seen significant declines in youth arrests and incarceration. Despite positive movement on important indicators, far too many youth—disproportionately youth of color—are incarcerated. Between 2000 and 2022, the number of youth held in juvenile justice facilities fell from 108,800 to 27,600—a 75% decline.

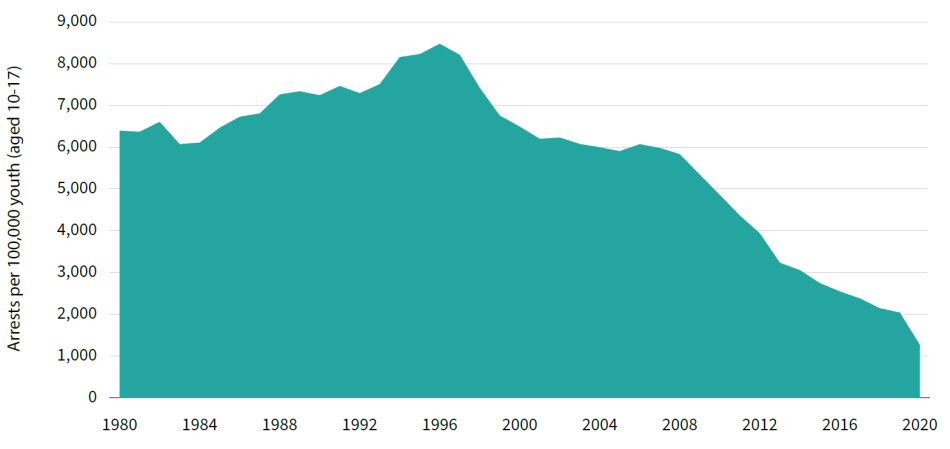

Youth Arrest Rates

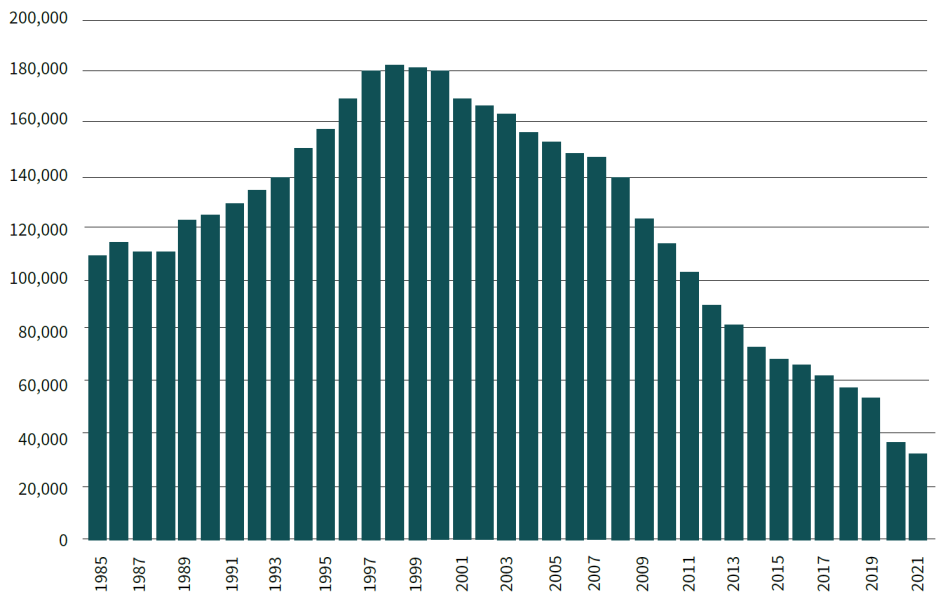

The arrest rate for people under 18 years old peaked in 1996 and has declined more than 80% since. Between 2000 and 2018, roughly 5% of youth arrests are for offenses categorized by the FBI as Part 1 violent crimes (aggravated assault, robbery, rape, and murder), though that proportion increased to 8% in 2020.

Figure 1. Youth Arrest Rates, 1980-2020

Source: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2023). Estimated number of juvenile arrests.

One-Day Count of Youth Incarceration

Between 2000 (the peak year) and 2022, the number of youth held in juvenile justice facilities on a typical day fell from 108,800 to 27,600, a 75% decline, likely reflecting both declines in youth offending and arrests during the Covid-19 pandemic and reduced use of incarceration for arrested youth to reduce the spread of Covid-19 in facilities.

This one-day count combines figures for two sets of youth. First, it includes those held in detention facilities (those awaiting their court dates or pending placement to a longer-term facility after being found delinquent in court). Second, it includes committed youth held in youth prisons, residential treatment centers, group homes, or other placement facilities (as a court-ordered consequence after being adjudicated delinquent in juvenile court). In 2021, 44% of youth in the one-day count were in detention and 53% had been committed to a secure placement facility (the juvenile equivalent of imprisonment).1 These counts do not include people under 18 held in adult prisons and jails.

Figure 2. One-Day Count of Youth Held in Juvenile Justice Facilities, 1975-2022

Sources: Hockenberry, S. (2024). Highlights from the 2022 Juvenile Residential Facility Census. National Center for Juvenile Justice. National Center for Juvenile Justice (2021). Juvenile residential facility census databook. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Sickmund, M. (2023). Residential placement trends 1975-2019. [Unpublished data, available upon request.] National Center for Juvenile Justice; Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, T.J., & Kang, W. (2023). Easy access to the census of juveniles in residential placement.

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Youth Incarceration

Youth of color are much more likely than white youth to be held in juvenile facilities. In 2021, the white placement rate in juvenile facilities was 49 per 100,000 youth under age 18. By comparison, the Black youth placement rate was 228 per 100,000, 4.7 times higher. Tribal youth were 3.7 times as likely (181 per 100,000) and Latino youth were 16% more likely (57 per 100,000). Asian American youth were the least likely to be held in juvenile facilities (13 per 100,000).

Figure 3. Youth Placement Rates by Race and Ethnicity, 2021

Rate per 100,000 Youth

Source: Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, T.J., & Kang, W. (2023). Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement.

| Decision Point | Black Youth | White Youth | Disparity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arrests per 100,000 youth (2020) |

2,487 | 1,080 | Despite modest differences in self-reported behaviors, Black youth are 2.3 times as likely to be arrested as are white youth. |

| Cases diverted from formal processing per 100 juvenile court cases (2021) |

37 | 49 | Among those youth referred to juvenile court for delinquency offenses, white youth are 31% more likely to have their cases diverted. |

| Cases detained per 100 juvenile court cases (2021) |

31 | 20 | Among those youth referred to juvenile court, Black youth are 60% more likely to be detained. |

| Cases committed per 100 juvenile court cases (2021) |

9.3 | 5.7 | Among those youth referred to juvenile court, Black youth are 63% more likely to be committed than white youth. Sources: |

Sources of Black-White Incarceration Disparities for Youth

Disparities in youth incarceration stem both from differences in offending and from differential treatment at multiple points of contact with the justice system. Table 1 above shows that Black youth have a greater share of arrests than white youth than their white peers, more likely to be detained upon their arrest, and receive harsher sanctions as they move through the system. Upon arrest, white youth are more likely to be diverted from formal system involvement compared with Black youth. When found delinquent (i.e., convicted in juvenile court), white youth are more likely to receive probation or informal sanctions, whereas Black youth are more likely to be incarcerated.

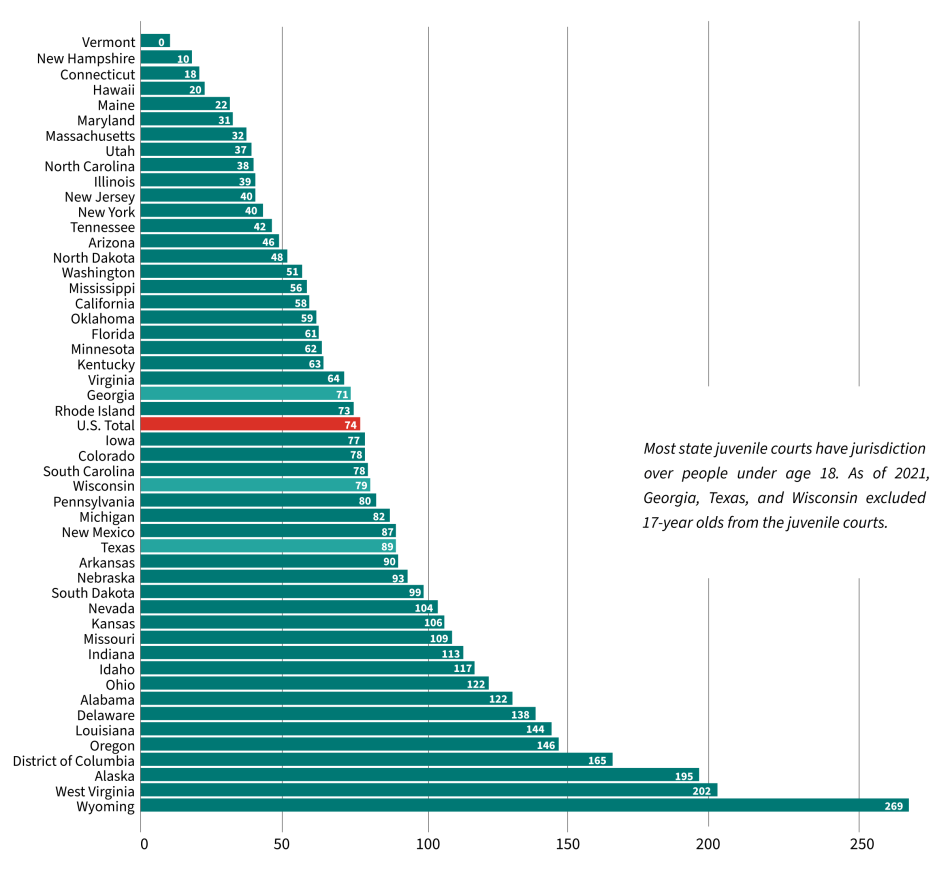

Combined Detention and Commitment Rates by State

On a typical day, 74 out of 100,000 youth nationwide are held in juvenile facilities, pre- and post-adjudication, with rates varying widely among states. The highest placement rate in 2021 was in Wyoming, where 269 out of 100,000 youth were in placement; the lowest rate was in Vermont , where no youth were held as of the one-day count in 2021.

Figure 4. Youth Residential Placement Rate By State (2021)

Placement rate for detained and committed youth per 100,000 youth2

For the purposes of this graph, youth are defined as age 10 through the maximum age of court jurisdiction in that state.

Source: Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, T.J., and Kang, W. (2023). Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

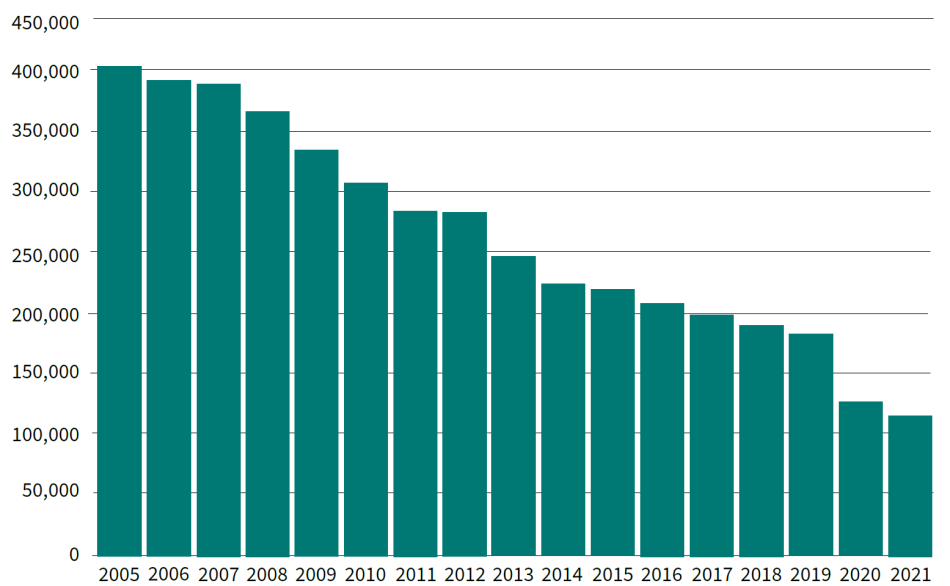

Annual Count of Detained Youth

Youth charged with or suspected of delinquency offenses (the juvenile justice system’s equivalent of criminal acts) may be confined in juvenile detention centers upon their arrest. In 2021, the most recent data available, roughly one in four (26%) youth referred to juvenile court upon arrest were detained, a rate consistent with recent prior years. In 2021, there were 113,000 detention admissions of youth on delinquency charges, representing a 72% decline since 2005.

This count does not include youth detained for status offenses,3 violations of probation, youth held in juvenile facilities on criminal charges, and those held in adult jails.

Figure 5. Annual Admissions to Juvenile Detention

New Delinquency Offenses Only, 2005-2021

Source: Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2023). Easy access to juvenile court statistics: 1985-2021.

Annual Count of Committed Youth

Youth who are adjudicated delinquent (the system’s equivalent of guilty) may be placed in facilities such as youth prisons, residential treatment facilities, group homes, or juvenile detention centers. In 2020, roughly one in 14 youth (7%) referred to juvenile court were committed to a placement facility, the juvenile system’s equivalent of imprisonment. In 2021, youth were committed 35,900 times for delinquency offenses (which are criminal acts when conducted by an adult), an 80% decline since 1999, the peak year. This count does not include youth admitted to these facilities for status offenses, violations of probation, or those in adult prisons.4

Figure 6. Annual Admissions to Juvenile Placement New Delinquency Offenses Only, 1985-2021

Source: Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2023). Easy access to juvenile court statistics: 1985-2021.

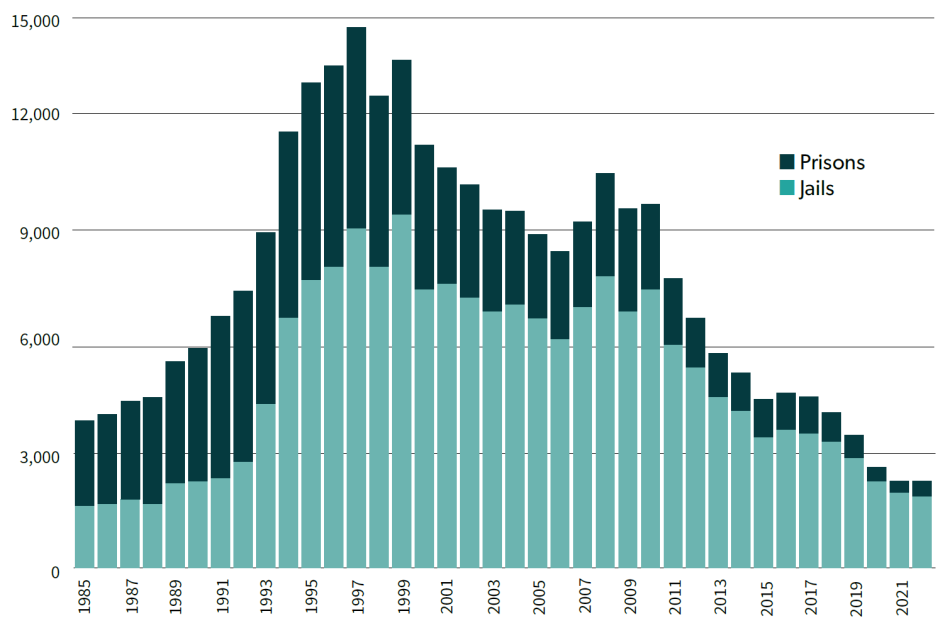

One-Day Count of Youth in Adult Prisons and Jails

In 2022,5 1,900 people under 18-years-old were held in an adult jail and 437 were serving sentences in an adult prison, representing an 84% decline from the peak year, 1997, when 14,500 youth were held in these facilities. In 2022, 23 states had no people under 18 in their adult prisons.6

Between 2021 and 2022, there was a notable rise in the number of youth in adult prisons, reflecting a 50% increase in only one year. Though this population is small in number, this one-year rise represents a reversal of a 25-year trend.

Figure 7. Youth in Adult Jails and Prisons (One-Day Count) 1985-2022

Sources: Austin, J., Johnson, K., & Gregoriou, M. (2000). Juveniles in Adult Prisons and Jails: A National Assessment. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance; Carson, E.A. and Kluckow, R. (2023). Prisoners in 2022 – Statistical Tables. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, plus prior editions; Zeng, Z. Carson, E.A., and Kluckow, R. (2023). Just the Stats; Juveniles Incarcerated in U.S. Adult Jails and Prisons, 2002–2021; Zeng, Z. (2023). Jail Inmates in 2022 – Statistical Tables. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, plus prior editions.

Decades of Progress, But Troubling Disparities Remain

The sharp declines in youth arrests and incarceration coincided, and we know that incarcerating fewer adolescents did not lead to increases in youth offending. However, the persistent racial and ethnic disparities in the youth justice system highlight the need to address the sources of those disparities wherever they emerge. Youth incarceration damages adolescents’ well being on multiple dimensions7, but effective alternatives exist that show lower recidivism and higher life achievement.8

The long-term portrait of youth justice is a promising one: far fewer youth are being arrested and referred to juvenile and adult courts than decades ago. These changes have allowed for the closure of more facilities, but additional progress is not only possible, but necessary. Youth given informal responses to their offending have better results, and the success of these diversionary programs provides a model for even more states to reduce the footprint of their justice systems.9

Glossary

- Adjudication refers to the juvenile court’s process that determines guilt.

- Detention refers to youth confined upon arrest and before their court disposition. Some youth in detention are awaiting placement. Such youth are generally held in facilities called juvenile detention centers. Youth in detention are suspected of delinquent acts or status offenses (such as incorrigibility, truancy or running away) or are awaiting the result of their court hearings.

- Commitment refers to youth confined in residential facilities after their adjudication. These facilities often have ambiguous names such as training schools, residential treatment centers, or academies.

- This is also called “placement,” a confusing term because “placement” can also refer to all youth held in juvenile facilities, including detained youth. The largest of these commitment facilities, typically state-run, are sometimes informally called “youth prisons.”

- Youth can also be committed to non-carceral facilities, such as group homes, wilderness camps or treatment centers.

- Referral to juvenile court equates to arrest. Juvenile court cases begin with a referral.

| 1. | The remainder are listed as being in placement for unknown reasons or as part of a diversion program. |

|---|---|

| 2. | For the purposes of this graph, youth are defined as age 10 through the maximum age of court jurisdiction in that state. |

| 3. | A status offense is a noncriminal act that violated the law because of a young person’s status as a minor. Status offenses include truancy, incorrigibility, running away from home, and curfew violations. |

| 4. | Data on youth held in adult prison are reported below. Annual commitments in the juvenile system for status offenses and for violations of probation are not available as part of the underlying dataset. |

| 5. | Counts are as of a single day. The number of people in prison is taken at year end and the number of people in jail is mid-year. |

| 6. | States with no youth in their adult prisons are: Alaska, California, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. |

| 7. | Mendel, R. (2023). Why Youth Incarceration Fails. The Sentencing Project. |

| 8. | Mendel, R. (2023). Effective Alternatives to Youth Incarceration. The Sentencing Project. |

| 9. | Mendel, R. (2022). Diversion: A Hidden Key to Combating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Juvenile Justice. The Sentencing Project. |