Out of Step: U.S. Policy on Voting Rights in Global Perspective

The United States is out of step with the rest of the world in disenfranchising large numbers of citizens based on criminal convictions.

Related to: Voting Rights, Collateral Consequences

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Overview of Trends in U.S.

- Recent U.S. Trends to Expand Voting Rights

- Remaining Obstacles in U.S.

- Spotlight on Impacted Individuals in U.S.

- How the U.S. Compares to the Rest of the World

- Global Trends

- Impacted Individuals from Around the World

- International Human Rights Law

- Recommendations

Executive Summary

The United States is an outlier nation in that it strips voting rights from millions of citizens1 solely on the basis of a criminal conviction.2 As of 2022, over 4.4 million people in the United States were disenfranchised due to a felony conviction.3 This is due in part to over 50 years of U.S. mass incarceration, wherein the U.S. incarcerated population increased from about 360,000 people in the early 1970s to nearly 2 million in 2022.4 While many U.S. states have scaled back their disenfranchisement provisions, a trend that has accelerated since 2017, the United States still lags behind most of the world in protecting the right to vote for people with criminal convictions.5

The right to vote is a cornerstone of democratic, representative government that reflects the will of the people. The international consensus on the importance of this right is demonstrated in part by the fact that it is protected in international human rights law. A majority of the world’s nations either do not deny people the right to vote due to criminal convictions or deny the right only in relatively narrow and rare circumstances.

This report highlights key findings since 2006:

- The United States remains out of step with the rest of the world in disenfranchising large numbers of people based on criminal convictions. In part, this is due to a punitive criminal legal system resulting in one of the world’s highest incarceration rates. As noted above, the country has disenfranchised, due to a felony conviction, over 4.4 million people who would otherwise be legally eligible to vote. This is also due to the laws in many US states that provide for broad disenfranchisement based on convictions. For this report we examined the laws of the 136 countries around the world with populations of 1.5 million and above, and found the majority—73 of the 136—never or rarely deny a person’s right to vote because of a conviction. We also found that, even when it comes to the other 63 countries, where laws deny the right in broader sets of circumstances, the US is toward the restrictive end of the spectrum and disenfranchises, largely through US state law, a wider swath of people on the whole.

- The United States continues to disenfranchise a wider swath of its citizens based on a felony conviction than most other countries, many U.S. jurisdictions have worked to expand voting rights to persons with criminal convictions since 2006.

Reforms in some jurisdictions within the United States and other countries have limited the loss of voting rights due to a criminal conviction. Among other types of reforms, most U.S. states no longer disenfranchise individuals permanently for life and many no longer disenfranchise individuals upon release from incarceration. These reforms have occurred through a combination of legislative change, amendments to state constitutions, court victories, and executive action. In some cases, however, as in Florida, expansion of rights restoration has been met with subsequent retrenchment. - The trend toward greater enfranchisement of people with prior criminal legal justice system involvement is global: outside of the United States, countries have also expanded rights restoration efforts. For example, in 2014 Egypt repealed a sweeping law imposing a ban on voting, without time limits, on every person convicted of an offense from voting without time limits. Tanzania’s High Court found a law that disenfranchised persons sentenced to imprisonment exceeding six months to be unconstitutional because it was too general and inconsistent with the country’s Constitution.

- Voters with criminal conviction histories in the United States experience practical obstacles to electoral participation. For example, changes in state law have resulted in voter confusion among people with criminal conviction histories and prosecution of individuals for good faith efforts at voting. And some states require criminal legal system-impacted citizens to provide documentation in order to register to vote, which may be burdensome to collect. But other localities within the United States and other countries have removed these barriers and improved justice-impacted voter participation.

- Officials within the United States and other countries have worked to address logistical barriers to the ballot. Within the United States, several localities – including Cook County (Chicago, Illinois), Harris County (Houston, Texas), and the District of Columbia – have established polling stations in local correctional facilities. Several nations have worked to address barriers to voting for persons in correctional facilities. For example, officials in several countries including Chile, Croatia, Greece, and the Netherlands allow or have plans to install polling stations in prisons to guarantee ballot access.

In sum: US laws denying the vote to persons with criminal convictions are extreme when compared with the laws of other countries.

Readers are encouraged to remain mindful of the overtly racist historical context for disenfranchisement laws in the United States, including chattel slavery and its legacies, as we imagine a path towards greater civic participation for all.

Introduction: U.S. Policy and Global Law and Practice on Disenfranchisement

The United States is more extreme than other nations in its continued denial of voting rights to citizens due to criminal convictions, despite some reforms. The United States is a world leader in its scale of imprisonment and imposes restrictions on voting rights on a substantial number of citizens impacted by the criminal legal system. The United States currently bans over 4.4 million citizens from voting due to felony convictions – a staggering figure that outpaces the rest of the world.6 In many cases in the United States, disenfranchisement results automatically from a conviction.7 Worse yet, for many people in the United States, the loss of the right to vote is mandatory and permanent, which belies the claim that US democracy represents the “will of the people.”8

A felony conviction in the United States often involves a prison sentence ranging from one year to life, life without parole (a sentence to die in prison), or the death penalty. People on average serve about 12 years in prison for federal felonies9 and 5 years on average for state felonies.10 People convicted of misdemeanors are most often detained in jails alongside people who are accused, but not convicted, of crimes. In the US, felonies include several types of unlawful conduct, including most frequently: drugs or public order offenses (weapons, tax, immigration offenses) at the federal level;11 and at the state level violent offenses (e.g. robbery, murder, rape), property offenses (e.g. burglary), or drug offenses.12 There are both state and federal crimes in the United States as well as local, state and federal elections; voters are often prevented from participating in federal elections due to state level convictions and vice-versa.

Felony disenfranchisement policies can be traced back to the time of the founding of the United States, having been carried over from the colonial period.13 The widespread denial of voting rights and its link to mass incarceration is grounded in the use of felony disenfranchisement laws that helped animate the racial caste system in the United States.14 Two interconnected trends – expansion of criminal laws targeting Black residents15 and the disenfranchisement of citizens with felony convictions16 – emerged during this time to lay the foundation for the mass disenfranchisement that we see in the United States today.

Many felony disenfranchisement laws date back to the Post-Reconstruction era following the end of the Civil War. During this period, Black people witnessed both the expansion and the restriction of their rights as full citizens. State lawmakers, particularly in the South, implemented criminal laws designed to target Black male citizens and criminalize Black life through “Black Codes.” Many states simultaneously expanded the number of crimes classified as a felony and enacted disenfranchisement laws that revoked voting rights for any felony conviction.17 For example, in Mississippi, voting restrictions were adopted based on prevailing perceptions of crimes believed more likely to be committed by Black men, such as burglary, arson, and theft.18

Further policies were enacted to restrict Black citizenship; many states enacted literacy tests and poll taxes as a means to limit the access of Black men to the ballot.19 Although the federal government officially barred some Jim Crow-era tactics in the Voting Rights Act of 1965, felony disenfranchisement laws remain in 48 states.20 Felony disenfranchisement laws remain a serious structural barrier to social, political, and economic justice for communities of color.21

Today, the impact of felony disenfranchisement laws on Black communities remains clear. In large part, this disparate impact of felony disenfranchisement results from disproportionate rates of felony arrests and convictions among Black Americans and other communities of color.22 Much of this effect reflects disparate law enforcement practices regarding drug offenses, with Black Americans being arrested for both drug possession and sale offenses at considerably higher rates than their proportion of drug use.23 While disenfranchisement policies disproportionately affect people of color, this is even more pronounced for incarcerated people.

The impact on the Black electorate is significant. One in 19 Black Americans of voting age is disenfranchised, a rate 3.5 times that of people who are not Black.24 5.3 percent of Black adults in the United States are disenfranchised, compared to 1.5 percent of the adult population that is not Black.25 More than one in 10 Black adults is disenfranchised in seven states – Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Kentucky, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Virginia according to estimates by The Sentencing Project.26 Although data on ethnicity in correctional populations are unevenly reported and undercounted in some states, a conservative estimate is that at least 506,000 Latinx Americans or 1.7 percent of the voting-eligible population are disenfranchised.27 In some states, like Florida, children (people below the age of 18) can be convicted of felonies under state law, and thereby deprived of the right to vote, in some cases permanently, before they even have had their first opportunity to legally vote.28

The collateral impact of mass incarceration on people in the United States includes disenfranchisement along with barriers to housing, employment and other markers of full participation in U.S. civil society. Racial disparities within the criminal legal system severely burden Black Americans, as well as other voters of color – effectively depriving entire communities of their political and economic power by blocking their access to the ballot box.

Overview of Trends in United States Legal Reforms

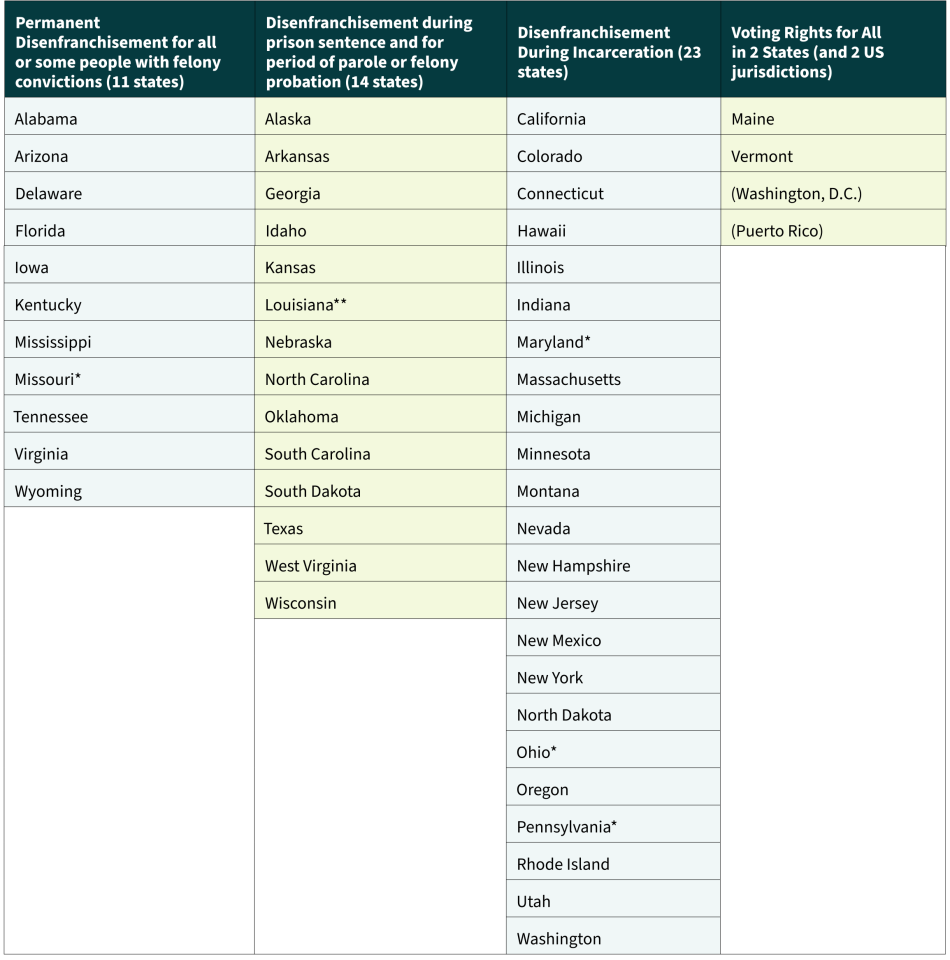

Table I: Disenfranchisement Laws in the United States29

*At least four states – Maryland, Missouri, Ohio, and Pennsylvania – permit permanent disenfranchisement for corrupt elections practices.

**In Louisiana, voting rights restored after 5 years on supervision.

Voting bans are established by the constituent US states, each with its own determination of circumstances under which people with felony convictions are excluded from the ballot. As illustrated below in Table I, Maine and Vermont are the only US states that allow people in prison to vote (as well as the District of Columbia and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico). It is noteworthy that Maine and Vermont are two of the least diverse states in the United States, with over 90 percent of the population identifiying as white in 2023.

In contrast, the states with the most restrictive disenfranchisement laws are those with the highest percentages of Black and Latinx people. Eleven US states permanently disenfranchise at least some people with felony convictions for the rest of their lives. Fourteen US states disenfranchise people both for the duration of their prison sentence and, upon their return to the community, during the time they are under parole or felony probation supervision. An additional state, Louisiana, restores voting rights to people on felony probation and parole once they have been out of prison for five years or more. Twenty-three states restore voting rights to people when they return to the community from prison, although at least four states that otherwise restore voting rights after a felony conviction permanently disenfranchise residents for certain election practices.30

The following two sections look at developments in felony disenfranchisement laws in recent years–both improvements that have been made in many states, but also the setbacks and remaining obstacles that have left so many returning citizens unable to vote.

Recent U.S. Trends to Expand and Protect Voting Rights

The movement towards restoring voting rights has gathered significant momentum in the US in recent years. Public opinion shows that a majority – 56 percent of likely US voters – support voting rights for people completing their sentence inside and outside of prison.31 A growing number of states have changed their voting laws to allow more Americans with previous convictions to vote.32 At the same time, millions of Americans with previous felony or misdemeanor convictions continue to face burdensome practical and legal hurdles in reclaiming their right to vote — hurdles that disproportionately impact people of color and people in lower income brackets.

Over the past several years, many states have expanded voting rights restoration. States that previously permanently disenfranchised citizens have created paths to restoration. States that previously extended disenfranchisement through completion of probation or parole have moved toward restoration at release from incarceration. And several states have implemented automatic restoration regimes to make it easier, as a practical matter, for returning citizens to begin registering and voting.

States have taken different paths to get there. In some states, governors have issued executive orders. In others, legislatures have passed new laws, or citizens have successfully voted through constitutional amendments or referenda. And sometimes, litigation (or the threat of litigation) has moved things forward.

Similarly, advocates and officials in different states have relied on different rationales for liberalizing felony disenfranchisement laws. Some have argued that once individuals complete their sentence for a felony conviction, they have paid off their debt to society and should not be subject to further punishment. Others emphasize the injustice that some of these individuals still pay their taxes and contribute to society, and yet they have no say in who their representatives will be. And many have noted the importance of second chances and helping individuals fully re-enter society.

Whatever the method, whatever the reason, many states are making their rights restoration laws less draconian. This section briefly examines the progress in these states.

States that no longer disenfranchise all people with felony convictions for life

Up until recently, there were four holdout states that imposed lifetime disenfranchisement upon conviction of a single felony: Virginia, Iowa, Kentucky, and Florida.33 Within the last decade, however, each of these states has expanded the availability of rights restoration either through executive order or a constitutional amendment. These reforms have faced contention and, at times, significant rollback through subsequent state or legislative action. Yet cumulatively, these voting rights expansions have resulted in re-enfranchising over 827,000 Americans in recent years according to The Sentencing Project estimates.34

In Virginia, in May 2013, then-Governor Robert F. McDonnell announced that he would automatically restore rights to those previously convicted of non-violent felonies who were not under state supervision, did not have pending felony charges, and had paid off any court imposed fees or restitution.35 An estimated 10,000 individuals became eligible for rights restoration based on this policy.36 In 2016, Governor Terry McAuliffe broadened the re-enfranchisement initiative by signing an executive order that restored voting rights to all individuals with previous felony convictions who had served all prison, parole, or probation sentences.37 More than 200,000 people would have regained the right to vote automatically pursuant to this executive order. However, the Virginia Supreme Court overturned the order, ruling that the governor lacked the authority under the state constitution to issue a blanket restoration order.38 Still, the governor restored voting rights on a case-by-case basis to an estimated 173,000 people.39 When Governor Ralph Northam took office in 2021, he began offering rights restoration to individuals who had completed their sentences for felony convictions, including those still on active supervision, which enabled an additional 69,000 people to apply for rights restoration.40 Current Governor Glenn Youngkin rescinded Governor Northam’s policy in March 2023, and offers rights restoration only after an individualized evaluation without specific criteria for those evaluations and with restoration moving at a much slower pace.41

In Florida, until 2019, discretionary executive clemency provided the only avenue to restoration.42 In 2016, Florida’s disenfranchised population was estimated to be over 1.6 million individuals,43 including more than one in five of the state’s Black voting-age population.44 In 2018, Florida voters passed Amendment 4, the Voting Rights Restoration Amendment, which amended the state constitution by “restor[ing] the voting rights of Floridians with felony convictions [except for persons with murder or crimes of a sexual nature offenses] after they complete all terms of their sentence including parole or probation.”45 In May 2019, however, the Florida Legislature passed a bill which defined “completion of all terms of sentence,” the operative language in Amendment 4, to include full payment of fines, fees, or restitution ordered by the court as part of the sentence.46 The new law established a pay-to-vote system, re-disenfranchising returning citizens47 with outstanding legal financial obligations and essentially removing the right to vote from those without financial means. Challenges to the law as an unconstitutional poll tax and violation of the Fourteenth Amendment were ultimately unsuccessful.48 While Florida lawmakers scaled back the impact of Amendment 4, the number disenfranchised as of 2022 declined to about 1.1 million.49

Kentucky’s constitution denies people with felony convictions the right to vote, unless they successfully petition the Governor to restore that right. As of 2016, more than one in four Black citizens in the state were unable to vote under this law.50 In 2019, Governor Andy Beshear signed an executive order automatically restoring the right to vote to individuals who have completed their sentences for nonviolent felonies.51 Those eligible for rights restoration under this law are not required to fully settle all court-ordered financial obligations.52 The order has restored the voting rights of an estimated 180,000 people, or five percent of Kentucky’s adult population.53 Currently, those convicted of a named class of violent crimes including homicide, sexual assault, treason, and election bribery are ineligible for voting rights restoration in Kentucky.

Until recently, Iowa’s constitution permanently disenfranchised all individuals with felony or aggravated misdemeanor convictions, unless they successfully petitioned the governor to restore their rights. In 2005, then-Governor Tom Vilsack signed an executive order restoring voting rights to a class of individuals with felony convictions.54 In 2011, Governor Vilsack’s successor Terry Branstad rescinded that order and signed an executive order requiring individuals convicted of felonies to settle all court-ordered fees, fines, and restitution before they become eligible to have voting rights restored.55 In 2014, the Iowa Supreme Court held that aggravated misdemeanors are not disqualifying, meaning that only felony convictions result in disenfranchisement.56 In 2020, Governor Kim Reynolds signed an executive order restoring voting rights to individuals with non-homicide convictions who have completed their sentences, including all terms of confinement, parole, probation, or other supervised release, irrespective of whether these individuals have settled other court-ordered financial obligations.57 The order restored voting rights to an estimated 20,000 people.58

States that have moved to voting rights restoration at release from incarceration

Several states previously required that citizens returning to the community complete probation or parole before regaining voting rights. Now, many are moving forward restoring voting rights at the time of release from incarceration, allowing people to register and vote while on supervised release.59 Connecticut, California, New York, New Jersey, Minnesota, Louisiana and Washington are some examples.

Before 2001, Connecticut’s disenfranchisement law prevented citizens convicted of a felony from voting while incarcerated, on probation, or on parole.60 In 2001, following a years-long grassroots campaign, then-Governor John G. Rowland signed into law legislation that restored voting rights to people on probation.61 In June 2021, Governor Ned Lamont signed into law a bill which restored voting rights to people on parole.62 As such, those who have fully completed their sentence or who are on parole or probation are automatically eligible to register to vote in Connecticut.63

In California, prior to 2020, individuals on parole for a felony conviction were ineligible to vote. In November 2020, California voters passed Proposition 17, a ballot measure that amended the state constitution to restore voting rights to those on parole.64 The measure was estimated to restore voting rights to about 50,000 Californians on parole, allowing them to join people on probation, who were already eligible to vote in California.65 Supporters of the ballot measure emphasized that these individuals should be able to shape the policies that affect their lives and that voting supports successful reentry by affirming that the voices of people on parole matter.66 In 2023, another proposed ballot measure was introduced in the California legislature to fully end felony disenfranchisement. If passed, that measure, ACA 4, would allow people in prison to retain their voting rights, bringing California in line with Maine, Vermont, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico.67

In New York, prior to 2021, individuals convicted of a felony were barred from voting or registering to vote while they were still under parole or any other post-release supervision.68 As of 2018, voting rights could be restored to returning citizens on parole via partial executive pardons on a case-by case basis.69 In 2021, New York passed a law allowing anyone who is not currently incarcerated and who is otherwise eligible to vote, including those on parole, to register to vote.70 The bill was supported by a coalition of various local and national organizations and law enforcement officials.71 Supporters believed that restoring voting rights to those on parole would facilitate community reintegration and participation in the civic process.72 Since the law passed, voting rights are automatically restored to individuals upon release from prison for a felony conviction, meaning New Yorkers can vote while still on parole or felony probation.73

Previously, New Jersey citizens who were serving a prison, parole, or probation sentence as a result of a felony conviction were ineligible to register to vote.74 In 2019, Governor Phil Murphy signed into law a bill that restored voting rights to people on parole or on probation for a felony conviction.75 It is estimated that about 83,000 people recovered their voting rights when the law went into effect.76

In New Mexico, state lawmakers repealed the lifetime felony disenfranchisement ban from 2001 by restoring the right to vote to all citizens convicted of a felony upon completion of their sentence. The reform expanded voting rights to nearly 69,000 residents. Officials streamlined the rights restoration process in 2005 through implementation of a notification process requiring the Department of Corrections to issue a certificate of completion of sentence to individuals who satisfactorily met obligations and to notify the Secretary of State when such persons become eligible to vote.77 During 2023, lawmakers enacted the New Mexico Voting Rights Act, House Bill 4, which included a provision automatically restoring voting rights to previously incarcerated residents following incarceration. The provision restored voting rights to more than 11,000 residents in New Mexico.78

Under the Minnesota Constitution, any citizen convicted of a felony is automatically disenfranchised until their civil rights have been restored. By 1963, the means for restoring voting rights occurred in only three ways: by a gubernatorial pardon, a court order, or automatically upon expiration of a sentence, which included any period of supervised release following release from prison.79 In 2023, the Minnesota Supreme Court upheld this disenfranchisement scheme as constitutional despite the disparate impact that it had on voters of color, suggesting that the Minnesota Legislature was the proper forum to expand rights restoration.80 Shortly thereafter, the Minnesota Senate passed a bill to restore voting rights to all individuals with felony convictions who are not currently incarcerated.81 Governor Tim Walz signed the bill into law in March 2023, and the law went into effect on July 1, 2023.82 Minnesota citizens are now eligible to vote upon release from prison and even during any court-ordered supervisory periods.

In Louisiana, the state constitution prohibits people “under an order of imprisonment” for a felony conviction from voting.83 Under this provision, Louisiana citizens who are serving a term of imprisonment for a felony conviction, or any election-related offense, are ineligible to vote.84 A 1976 law expanded that population to also include those on parole or probation for a felony conviction.85 However, the legislature passed a law in 2019 to restore voting rights to individuals convicted of felonies who have completed their sentence of parole or probation or, for those still on parole or probation, have not been incarcerated within the last five years.86 An author of the bill cited that because returning citizens pay their taxes, they should have a chance to vote for their representatives.87

The Washington state constitution provides that “all persons convicted of infamous crime unless restored to their civil rights . . . are excluded from the elective franchise.”88 Prior to 2021, in order to vote, individuals with felony convictions had to complete any sentence of community custody—supervised release—which could range from months to the rest of their lives.89 Further, those who were unable to pay court-ordered fees or restitution could have their voting rights revoked.90 In 2021, Washington state legislators passed House Bill 1078 to automatically restore voting rights to any individual with a felony conviction who is not currently in total confinement.91 Since the law took effect in 2022, individuals now automatically regain their voting rights as soon as they are released from incarceration, though they must re-register in order to vote.92

States that have made other recent moves to restore voting rights

Other states have made different types of improvements to their rights restoration regimes: for instance, allowing incarcerated individuals to vote; reducing the types of felonies that trigger disqualification; removing requirements to pay legal financial obligations; and removing waiting periods before an individual can be re-enfranchised. As some examples:

In 2020, Washington, D.C., joined Vermont, Maine, and Puerto Rico as the only U.S. jurisdictions that allow individuals to vote while they are still incarcerated for a felony conviction.93 The D.C. Council amended the election law to require the Board of Elections to “provide to every unregistered qualified elector in the Department of Corrections’ care or custody, and endeavor to provide to every unregistered qualified elector in the Bureau of Prisons’ care or custody, a voter registration form and postage-paid return envelope . . . a voter guide, educational materials about the right to vote, and an absentee ballot with a postage-paid return envelope.”94 Those incarcerated for a felony offense, under court supervision, such as parole or probation sentences, or residing at a halfway house after release, are now eligible to vote.95

The Alabama state constitution provides that “no person convicted of a felony of moral turpitude” may vote.96 For years, Alabama interpreted this provision to cover every felony conviction except a list of five, meaning that most people with felony convictions in the state were permanently barred from voting and ineligible for a pardon.97 Nearly a third of the disenfranchised individuals were Black men.98 In 2017, Alabama residents with felony convictions challenged the state constitution’s “moral turpitude” language on constitutional grounds.99 Before the district court decided the case, the Alabama legislature passed a bill, titled the “Definition of Moral Turpitude Act,” establishing a comprehensive list of felonies that involve moral turpitude.100 Advocates for this bill emphasized that those wanting to rebuild their lives deserve a fairer chance at regaining voting rights, a basic right of U.S. citizenship.101 When Alabama Governor, Kay Ivey, signed the bill into law, individuals whose felony convictions were not included in the enumerated offenses regained their right to vote. These individuals can now register to vote without full payment of court-ordered fees, fines, or restitution, and even if still incarcerated, vote via an absentee ballot.102 Those convicted of a crime of “moral turpitude” may regain the ability to vote only by applying for a pardon or a Certificate of Eligibility to Register to Vote with the Board of Pardons and Paroles.103 After the law went into effect, Alabama refused to spend resources informing people newly enfranchised by the law that they had regained their rights to vote.104

Arizona’s rights restoration regime depends on one’s sentence and how many felony convictions a person has. If an individual has been convicted of a single state felony offense, their right to vote is automatically restored as soon as the court-imposed sentence, including any supervised release period, is completed.105 A law passed in 2019 removed the requirement for these individuals to settle all court-ordered fines before their rights are restored.106 If the individual has been convicted of two or more felony offenses, either in a single criminal case or in separate cases, the individual may petition the court that sentenced them to have their voting rights restored upon completion of probation or absolute discharge.107 (A law passed in 2022 removed a previous two-year waiting period for individuals with multiple convictions to petition for voting rights restoration.108 The court has discretion on whether or not to grant a petition for voting rights restoration.109

In 2013, the Delaware state legislature passed a constitutional amendment to eliminate a five-year waiting period for individuals who have completed their sentences for felony convictions to regain their voting rights.110 Those whose convictions make them eligible for automatic rights restoration under the law must first complete any sentence of imprisonment, parole, work release, early release, supervised custody, probation, or community supervision.111 As of 2016, applicants are not required to pay legal financial obligations associated with their conviction for their sentence to be considered completed for eligibility purposes.112 The law does not apply to those whose convictions are deemed to be a “disqualifying felony”; those individuals can only vote after a pardon from the Governor.113 Disqualifying felonies include murder, manslaughter, sexual offenses, and felony offenses against public administration such as bribery.114

In recent years, many states have expanded access to voting rights after criminal conviction, as these examples illustrate. Other states including Nevada, Colorado, Oklahoma, and Wyoming have also liberalized their rights restoration laws in the same period.115 Around the country, the overall trend is toward re-enfranchisement. That said, practical obstacles to exercising those rights remain in many states.

Remaining Obstacles to Rights Restoration in the United States

Despite advances in legal eligibility to vote, substantial practical obstacles remain to voting access for returning citizens.

Voter confusion

Changes in state law regarding rights restoration has resulted in some voter confusion among returning citizens. Legal changes or advancements are not always stable over time. Gubernatorial executive orders have proven unstable; for example, Virginia, Iowa, and Kentucky have had governors issue conflicting executive orders over time, expanding rights and then rolling them back.116 Litigation victories can also prove illusory or volatile; advocates for rights restoration in Mississippi and North Carolina won court victories re-enfranchising some returning citizens for a time, but both victories were subsequently overturned or vacated on appeal.117 Even states that passed legislation or constitutional amendments—arguably the most stable form of legal change—have seen some retrenchment. In Florida, for instance, voters amended the state constitution to expand rights restoration, only to see the legislature significantly curtail those rights through subsequent legislation. These legal see-saws result not just in fewer rights for returning citizens, but confusion for voters trying to keep track of the fluctuating state of the law.

Due to this legal instability, and the fact that different states have vastly different laws for voting rights restoration, even election officials tend to be confused as to eligibility rules, which itself can exacerbate voter confusion. Frequently, corrections officers do not provide any information to returning citizens as to their voting rights upon release.118 Even election officials responsible for a state’s voting rights restoration process express confusion as to the mechanics of those processes.119 Post-release procedures for restoring one’s rights to vote can be complex and burdensome—and even in states that automatically restore voting rights, many are unaware of their eligibility after release.120 As one example, in Florida, it is often virtually impossible to know one’s voting eligibility,121 as the state doesn’t have a centralized system to look up what one owes in legal financial obligations122 and only extremely rarely issues individualized guidance to voters about their eligibility.123 Likewise, the lack of communication, information, and clarity on voting eligibility for returning citizens in Alabama has dampened the practical import of the policy improvements discussed previously in Section I.104

Paperwork & documentation requirements

Some states that have expanded rights restoration still require that returning citizens provide various forms of documentation in order to register to vote. For example, in Louisiana, these individuals must request a “Voter Rights Certificate” from the Division of Probation and Parole and present it in person, together with a paper Voter Registration Application, to the Registrar of Voters in order to register to vote.125 The Voter Rights Certificate attests that the individual has completed their parole or probation and has not been incarcerated within the last five years. Several formerly incarcerated people testified at a legislative hearing in 2023 about the confusion and barriers they have run into when trying to regain their voting rights, including this burdensome requirement.126 Louisiana could instead provide this information directly to the Registrar or allow citizens to present the certificate online or via mail.127

Compounding collateral consequences and depressed voter turnout

Criminal convictions often carry severe collateral consequences. While those consequences vary across jurisdictions, prior criminal convictions frequently saddle individuals with barriers to accessing employment, professional licensing, public assistance, housing, education, and financial aid.128 Those collateral consequences lower an individual’s income prospects and place returning citizens at especially high risk of entering or staying in poverty.129 Lower income and poverty are strongly associated with reduced political participation.130 In some jurisdictions, returning citizens are prevented from getting a driver’s license,131 another practical barrier to voting when presenting identification is required. Some states also bar returning citizens from other forms of civic participation—like serving on a jury or holding public office.132

These collateral consequences often dramatically increase returning citizens’ voting costs – the burdens these voters face as they attempt to exercise their right to vote – and thereby decrease their likelihood of casting a ballot.133

“Pay-to-vote” rights restoration systems

In many states, returning citizens become eligible to vote only upon payment of various legal financial obligations—fees, costs, fines, and/or restitution that courts have imposed on them.134 Those requirements keep returning citizens from voting when they can’t fully pay off those debts. This is common, particularly given that returning citizens are disproportionately likely to be indigent and suffer from aforementioned collateral consequences that make it harder for them to escape poverty. In Alabama, for example, about one-third of applications for rights restoration are denied due to court debts.135 Because of the racial wealth gap, and the racial disparities in criminal legal system impacts discussed in the introduction, these “pay-to-vote” schemes leave Black citizens especially likely to be disenfranchised.136

Fear of voting due to threat of criminal prosecution

States regularly prosecute voters for trying to vote when they don’t realize they aren’t eligible to do so due to a felony conviction. Alarmingly, this is happening with increasing frequency in many states such as Florida,137 Texas,138 Tennessee,139 North Carolina,140 Minnesota,141 and Georgia,142 among others. Typically, news reports show that these returning citizens made good-faith mistakes as to their voting eligibility—often due to the aforementioned, widespread voter confusion around rights restoration under state law—and were surprised to later face arrest for voting.143 Evidence also shows that these prosecutions for voting while ineligible tend to have a chilling effect on political participation, as even eligible voters in communities impacted become fearful of voting.144

Obstacles to voting in jails

Most individuals incarcerated in jails have not been convicted of crimes and remain eligible to vote.145 Some also face misdemeanor charges and are disenfranchised in certain states while completing their sentence.146 But practical barriers prevent these eligible voters from registering to vote or casting a ballot from jail. People in jails often do not know they retain their voting eligibility and aren’t given accurate information about their voting rights from either state officials or facility staff.147 And even where individuals realize they are eligible, they often have to overcome a myriad of logistical hurdles to register and cast a ballot: the lack of in-person voting opportunities in jails, learning and meeting the deadlines for registering and voting, requesting and submitting both a registration form and a ballot (often with mail delays and without phone or internet access), keeping their registration address current, and getting an ID where states require one to vote. Voters in jails also may have privacy concerns about staff handling and reviewing their mail.148 Some states have laws that make ballot return by most non-family members illegal, which would likely prevent jail staff from returning ballots on their behalf.149

As one example, in Delaware, evidence shows that not one single voter living in a jail voted in the November 2020 election.150 That happened in part because inaccurate information was posted around jails, staff weren’t trained on how to handle ballots, and individuals incarcerated in solitary confinement weren’t allowed to register.151 Similarly, in Connecticut, thousands of voters were disenfranchised in 2020 because they had no way to get and return their ballots. The absentee voting process required sending and receiving multiple mailings, which was difficult or impossible for many.152 Workable models exist for removing obstacles for eligible voters who are pretrial or completing misdemeanor sentences in local jails; for example, operating polling sites at jails or waiving absentee voting requirements specifically for incarcerated voters.153 Practitioners and advocates are working to implement ballot access practices in jurisdictions where eligible voters completing felony sentences in prison can participate in the franchise. In the District of Columbia, officials with the Board of Elections implemented practices as required by the DC Restore the Vote Act to guarantee ballot access for eligible voters completing felony sentences in prison or jail.154 In Puerto Rico, polling stations in prison facilities throughout the jurisdiction contributed to more than 6,100 persons voting in the 2016 presidential primary.155

A Spotlight on Impacted Individuals in the United States

It is pivotal to remember that at the heart of this conversation—about the legislative campaigns, the legal victories and defeats, the advances and retrenchments—are fellow citizens, neighbors, friends, and family. Below are stories of a few returning citizens who have been affected by recent changes in felony disenfranchisement policy.

Debbie Graner, Kentucky

Before 2019, some 300,000 Kentuckians could not vote due to a prior felony conviction. One of them was Debbie Graner. Though she completed probation in 2017, Debbie was still disenfranchised due to her felony conviction. Kentucky’s draconian law ensured that the state had the third highest disenfranchisement rate and the highest Black disenfranchisement rate in the nation.156 Governor Andy Beshear’s 2019 Executive Order, however, restored the right to vote for Debbie and an estimated 180,000 Kentuckians.53 When she voted for the first time in years in 2020, at the age of 69, Debbie felt a renewed sense of appreciation for the ballot box.158

Still, there was a problem. Although the 2019 order expanded voting rights, Kentucky did not have a formal mechanism for notifying people or helping them to get registered, leaving many unable to take advantage of their newfound eligibility. Noticing this gap, Debbie and the Kentuckians for the Commonwealth (KFTC) launched the Kentucky Democracy Project to help register voters who are unaware that their right to vote has been restored and to advocate for Kentuckians who are still being deprived of their right to vote.159 Debbie notes this mission is so important because “being able to vote is healing,” as it “[makes] you feel like a complete person and a member of society.”160 Debbie and her KFTC colleagues are also working to advocate for further progress for returning citizens in Kentucky: “most of us [with criminal histories], even though we have become law-abiding and productive citizens who pay taxes, still have difficulty finding suitable employment and adequate housing. Even though we often work to assist others, stay out of legal trouble or recover from addictions, [some of us] will never have our voting rights reinstated unless a state constitutional amendment is passed.”161

…being able to vote is healing,…you feel like a complete person and a member of society.”

Debbie Graner

Checo Yancy, Louisiana

Checo Yancy voted for the first time on September 29, 2019, at the age of 73 years old, nearly 40 years after he was disenfranchised when he was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment in 1983.162 In 1995, the Governor of Louisiana commuted his sentence to 75 years, and he was released on parole eight years later. During his 20 years of incarceration, Checo joined a prison ministry, volunteered for a hospice program, and taught fellow incarcerated persons how to read, among countless other undertakings.163 Borne out of the conditions he experienced during the 20 years he spent in the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, Checo developed a passion for advocacy and an interest in civic engagement. Checo and longtime friend Norris Henderson, who were both released from Angola in 2003, are founding members of Voice of the Experienced, a nonprofit organization that advocates for full civil rights restoration for formerly incarcerated people. “We actually started this organization inside of Angola almost 40 years ago,” Checo said, “and we wanted to get our family members and everybody involved in understanding that voting…is the way that you [change the law].”164

I vote because my vote is my power. My vote is my voice. When I vote, I’m voting for my children. I’m voting for my granddaughter. I vote because my voice matters.

Checo Yancy

Checo is also the policy director of Voters Organized to Educate, a non-profit specifically focused on building electoral power and mobilizing voters to effect change within Louisiana’s criminal legal system.165 Through this work, Checo played an active and pivotal role in getting the Louisiana State Legislature to pass a new rights restoration law in 2018, which granted voter eligibility to thousands of citizens.166 The law finally made Checo, who is still on parole for his 1983 conviction, eligible to vote. With his own rights now restored, Checo spends his days educating, mentoring, and advocating for the 1,000 people who are released from incarceration every month in Louisiana. After so many years, voting can now be a source of pride and a statement of self-determination for Checo: “I vote because my vote is my power. My vote is my voice. When I vote, I’m voting for my children. I’m voting for my granddaughter. I vote because my voice matters.”167

Jennifer Schroeder, Minnesota

Jennifer Schroeder was a 30-year-old new mother when she was sentenced to one year in prison and 40 years of probation for felony drug possession charges in 2014. Jennifer’s bloated probationary sentence guaranteed that she would be ineligible to vote until 2053, at the age of 71.168 Feeling alienated from society and unsure of her future, Jennifer fought hard to reestablish her career after her conviction. She underwent substance use treatment, went back to school, and earned a degree from Minneapolis Community and Technical College, using her education and personal experience to become a counselor.169 In 2019, she became the lead plaintiff in a lawsuit brought by the ACLU and ACLU of Minnesota challenging the state’s felony disenfranchisement policies.

By sharing her story in courtrooms, to legislators, and in the media, Jennifer set out to “represent [formerly incarcerated people] in a positive light, and to take down that stigma that keeps [them] feeling apart when [they] return to [their] communities.”170 As noted earlier in this report, Minnesota passed a new law in 2023 restoring voting rights upon release from confinement, and Jennifer was there to witness it. “Thanks to this law that changes today, the voices of those who have struggled will no longer be silenced,” Jennifer said at the bill-signing ceremony.171 “The moment we cast our ballot, we are taking part in something much bigger than ourselves … It’s especially important for people who have been incarcerated … Voting makes us feel like we belong, like we can actually reintegrate into society and have the power to shape our futures.”172 Now that Jennifer and an estimated 50,000 of her peers are eligible to vote, she has found a new avenue for her advocacy efforts: fighting for reforms that would cap probation sentences at five years, so that formerly incarcerated people like her can get their voting rights restored even in states that maintain disenfranchisement for those on supervised release. Empowered by her experience as a plaintiff and civil rights advocate, Jennifer is even considering going back to school to get her degree in political science so that she “can fight for change at the macro level.”173

The moment we cast our ballot, we are taking part in something much bigger than ourselves … It’s especially important for people who have been incarcerated … Voting makes us feel like we belong, like we can actually reintegrate into society and have the power to shape our futures.

Jennifer Schroeder

How the United States Compares to the Rest of the World

The sweeping nature of disenfranchisement in the United States is out of step with the rest of the world. For this report, we examined the laws and practices of 150 countries around the world with populations of 1.5 million and above.174 We determined that 14 of these countries have not commenced holding or do not ever hold national elections, are under military rule, or have no legal system allowing for voting rights in national elections.175 The remaining 136 countries vary widely in the health of their democratic systems and protections for related rights. For the purposes of this report, we did not analyze the political systems in these 136 countries beyond determining whether elections were conducted; we focused solely on legislative and constitutional provisions governing voting rights in connection with criminal convictions.176

Countries with few legal restrictions on voting for people with criminal convictions

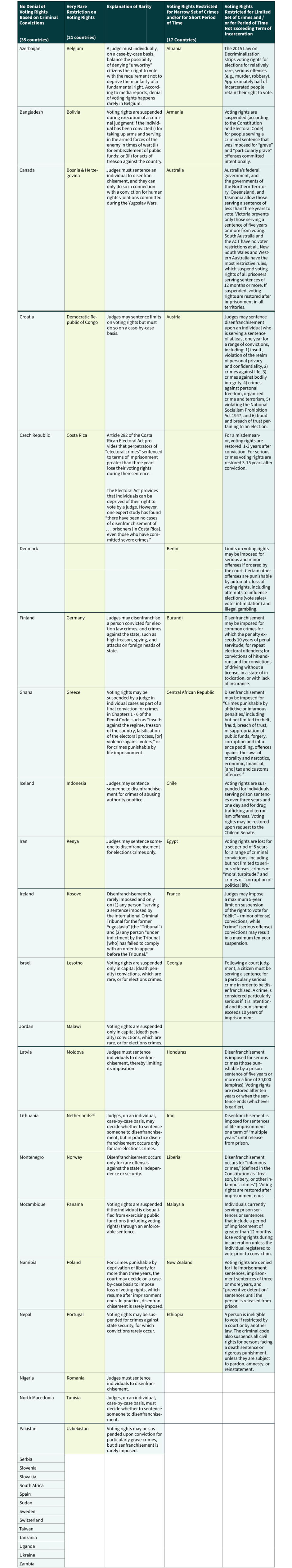

As Table II below shows, the majority of the countries we examined—73 of the 136, or 54 percent—have laws that are far more protective than the United States of the voting rights of people with criminal convictions: 35 countries do not ever restrict voting rights based on criminal convictions, 21 very rarely limit the right to vote, and 17 restrict voting rights for a narrow set of crimes or for limited periods of time. A majority of the world’s countries do not disenfranchise their citizens nearly as often as most U.S. states.

Table II. Seventy-Three Countries that Do Not or Rarely Deny Voting Rights Due to Criminal Convictions

Government of Azerbaijan. “Election Code of the Republic of Azerbaijan,” Retrieved May 9, 2024.; Azerbaijan “Constitution of 1995 with Amendments through 2016,” Retrieved May 9, 2024.

Prison Insider. (2019). Belgium: No hope for improvement in voting system. See also Penal Reform International, Penal Reform International. (2016). The Right of Prisoners to Vote: A Global Overview.

Government of Albania. Article 35, Section VII, The Albanian Criminal Code. OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, 2021. p.11. Retrieved May 9, 2024.

Government of Bangladesh. Article 122, Constitution of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Collaborators Order. Retrieved May 10, 2024.

Government of Bolivia. Article 28, Section II of the Bolivia Constitution. Retrieved May 10, 2024.

Government of Armenia. Article 48 of the Armenian Constitution. Article 48. Retrieved May 10, 2024.; Armenian Electoral Code, Article 2, part 4.

Government of Canada. Sections 244-45, Canada Elections Act (S.C. 2000). Retrieved May 10, 2024.

Government of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Article 1.6-7, Election Code of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Retrieved May 10, 2024.

Churchill, M. (2020). ”Voting Rights in Prison: Issues Paper,” Pro Bono Centre, University of Queensland.; Hill, L. (2016). Precarious Persons: Disenfranchising Australian Prisoners. Australian Journal of Social Issues.

Government of Croatia. Croatia Constitution of 1991 with Amendments through 2013, Article 45. Retrieved May 12, 2024.; European Commission for Democracy Through Law. (2020. October 8). “Report on Electoral Law and Electoral Administration in Europe.

Government of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Electoral Law, Article 7, Democratic Republic of Congo.

Government of Austria. Austrian Federal Law on National Council Elections, Part II, Section II, § 22; Austrian Special Part of the Criminal Code § 278a to § 278, Section 14-18, 24 or 25; Austrian National Socialism Prohibition Act 1947.

Government of Czech Republic. Czech Constitution, Art. 18(3) and Czech Republic Electoral Code, Article 6(1)(c).

Government of Costa Rica. Electoral Act, Costa Rica, Article 144.

Alfaro-Redondo, R. (2015). “Access to Electoral Rights Costa Rica,” European Union Democracy Observatory. FierroNavarro, C. M. (2021). Fierro, “International comparative study on electoral inclusion,” Instituto Nacional Electoral International Affairs Unit.

Government of Denmark. Denmark’s Folketing (Parliamentary) Elections Act 2020, Part 1, Art. 1(1) and Part 8, Art. 54(3).

Government of Benin. Benin Penal Code Art. 89.

Government of Finland. Electoral Law of Finland, Section 9.

German Electoral Code, Sections 13 and 45(5).; German Criminal Code §§ 92a, 101, 102(2), 108(c), 109(i).

Burundi’s Electoral Code, Article 9.

Constitution of Ghana, Article 42;. Supreme Court of Ghana. (2010). Centre for Human Rights & Civil Liberties v. Attorney-General and Electoral Commission, Civil Appeal No. JI/4/2008 & JI/5/2008).

Presidential Decree of Greece (2012); Government Gazette. (2021). Law 4084; European Parliament. (2024). “‘Prisoners’ Voting Rights in European Parliament Elections”.

Central African Republic, Article 5.

Constitution of Iceland, Article 33.; Elections Act of Iceland, Chapter II, Article 3; Elections Act of Iceland, Article 69.

Government of Indonesia. Indonesia Penal Code, Article 87.

Government of Chile. Constitution of Chile, Article 16(2);. (2020, September). “Sufragio de Personas Privadas de Libertad,” p. 7; Fernández, M.J. and Oberti, A. (2021)., “Voting in Prisons is a Right,” CiperHistoria De La Ley. (1980). Constitucion Politica de la Republica de Chile de 1980., p. 51; Constitution of Chile, Article 16(3); and “Código Electoral. (2009). Publicada en el Alcance 37 a La Gaceta n.° 171. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

Government of Iran. Law for the Elections of the Islamic Consultative Parliament, Iran, chapter 3, article 27; Human Rights Watch. (2021). World Report, Country Chapter: Iran. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

Constitution of Kenya, Article 83. (2010); National Crime Research Center. (2016). Kenya Election Offenses Act of 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

Government of Egypt. Egypt, Law on the Regulation of the Exercise of Political Rights. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

Government of Ireland. Constitution of Ireland, Article 16; Electoral Amendment Act, 2006, Constitution of Ireland (2006). Retrieved May 14, 2024.

Government of Kosovo. Electoral Code of Kosovo, Article 5.; Electoral Rule of Kosovo (2009). Number 04/2008.

Government of France. Penal Code of France, Article 131- 26. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

Knesset Elections Law (Consolidated Version) (originally adopted in 1969), Chapter Two: General Provisions; Hartman, B. (2015). “Incarcerated people of the Election: Thousands of Inmates Line up to Vote at Facilities Across Israel,” The Jerusalem Post.

It is important to note that Israel denies the millions of Palestinians in the Occupied Palestinian Territory living under its rule the right to vote for the authority that exercises primary control over their lives.

Government of Lesotho. Constitution of Lesotho, Article 51.7.; Lesotho National Assembly Electoral Act of 2011, Section 5(2).

Government of Georgia. Constitution of Georgia, Article 24(2). Retrieved May 14, 2024.

Government of Jordan. Election of the House of Representatives, Article 3. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

Government of Malawi. Constitution of Malawi, Article 77(3). Retrieved May 14, 2024.

Government of Latvia. Election Code of Latvia, Article 45.1. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

Government of Moldova. Electoral Code of Moldova, Articles 14 and 78(3)(b); BBC News. (2012). “Prisoner Votes by European Country,” Retrieved May 14, 2024.

Government of Honduras. Penal Code of Honduras, Articles 13, 35, 36, and 42. Criminal Procedure Code of Honduras, Article 445.

Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. (2020). Parliamentary Elections in Lithuania. Retrieved May 14, 2024.; Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. (2020). Needs Assessment Mission Report. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

Government of the Netherlands. Netherlands Penal Code, Article 28. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

Government of Iraq. Iraq Penal Code, Section II, Para. 95 and 96. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

European Commission for Democracy Through Law. (2020); Government of Montenegro. Electoral Code of Montenegro; Official Gazette of the Republic of Montenegro. (2018). Criminal Code of Montenegro, Retrieved May 14, 2024.

Government of Norway. (2017). The main features of the Norwegian electoral system. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

Government of Liberia. Constitution of Liberia. (1986). Liberia New Elections Law, Section 5.1. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

Government of Mozambique. (2007) Constitution of Mozambique, Article 61. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Panama. (2007). Electoral Code of Panama, Article 9. Retrieved May 14, 2024. Government of Panama. Panama Electoral Code, Art. 521. Retrieved May 14, 2024; Redacción Digital La Estrella. (2009). “Incarcerated People Vote for the First Time” La Estrella de Panamá; Panamá América; Redacción Panamá América. (2018). “More than 800 Inmates Receive Ballots to Vote in 2019 Elections.” Panamá América.

Government of Malaysia. (2007). Malaysian Constitution, Article 119(3); In 2016, Malaysia’s High Court held that the Constitution permits individuals to vote who had registered before their conviction. Astro Aswani, A. (2016). “Court Dismisses Anwar’s Suit over Right to Vote.”

Legal Assistance Centre of Namibia, “Proving Citizenship for Voting.” Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Poland. (2011). Election Code of Poland, Article 10. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of New Zealand. (1993). New Zealand Elections Act of 1993 (as amended), Section 80(d). Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Nepal. (2016). Constitution of Nepal, Articles 84, 176, 222 and 223; Post Report. (2022). “Top court orders government to make arrangements for prisoners to vote.” The Kathmandu Post.

Government of Portugal. (2007). Criminal Code of Portugal, Articles 246, 346. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

Government of Ethiopia. (2004). Electoral Law of Ethiopia Amendment Proclamation, 1162/2019, Part III, Chapter 1, Paragraph 18.3(b). Retrieved March 5, 2024.

Government of Nigeria. (2022). Electoral Act of Nigeria. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Romania. Law 33/2017 of Romania, Article 5(6). Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of North Macedonia. North Macedonia Electoral Code, Article 113(1);. Balkan Insight. (2009). “Displaced, Incarcerated people Vote in Macedonia Poll,” Retrieved May 15, 2024; Inside Time. (2015). “Prisoner Voting in Europe,” Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Tunisia. (2022). Electoral Law of Tunisia (Decree No. 55 of 2022), Article 6; Government of Tunisia. (1913). Tunisia’s Criminal Code, Article 5, Article 62. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Pakistan. Constitution of Pakistan, Section 106. Retrieved May 15, 2024.; Government of Pakistan. (2020). Pakistan Election Act, Section 93(d). Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Uzbekistan. Electoral Code of Uzbekistan, Article 5. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Serbia. (2006). Constitution of Serbia, Article 52. Retrieved May 15, 2024; BBC News. (2022). “Prisoner Votes by European Country”. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

European Commission for Democracy Through Law (Venice Commission). (2020). “Report on Electoral Law and Electoral Administration in Europe,” para. 66. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

European Parliament. (2024). “Prisoners’ voting rights in European Parliament elections.” Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of South Africa. The Constitution of South Africa, Section 19(3)(a). Retrieved May 15, 2024.; Constitutional Court of South Africa. (2004). Minister of Home Affairs v. National Institute for Crime Prevention and the Re-Integration of Offenders (NICRO) and Others, para. 80. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Spain. (1985). General Electoral Law of Spain, Organic Law 5/1985, Third Article 1(a). Retrieved May 15, 2024; Government of Spain. (1995). Penal Code of Spain (as amended), Organic Law 10/1995, November 23, 2995. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

Government of Sudan. (2019). Constitution of Sudan, 2019. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Orr, G. (1998). “Ballotless and Behind Bars: Denial of the Franchise to Incarcerated People,” Federal Law Review, Vol. 26.

Government of Switzerland. (2014). Federal Constitution of Switzerland, Article 136. Retrieved May 15, 2024; BBC News. (2022). “Prisoner Votes by European Country”. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Taiwan. Penal Code of Taiwan, Article 36. Retrieved May 15, 2024.; Jono Thomson, J. (2023). “Taipei court rules in favor of prisoner’s right to vote.”

Government of Tanzania. Constitution of Tanzania. Retrieved December 4, 2023; Government of Tanzania. (2023). National Elections Act of the United Republic of Tanzania. Retrieved December 4, 2023; High Court of Tanzania. (2022). Civil Cause Number 3 of 2022. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

Ugandan High Court. (2020). Kalali v Attorney General & Anor (Miscellaneous Cause No. 35 of 2018) [2020] UGHCCD 172. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Ukraine. Constitution of Ukraine, Article 71. Retrieved May 15, 2024; BBC News. (2022). “Prisoner Votes by European Country”. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Africa Criminal Justice Reform. (2020). “The Right of Incarcerated people to Vote in Africa,”[Fact Sheet]. Retrieved May 15, 2024; Muyatwa Legal Partners. (2020). “The right of incarcerated people to vote under current Zambian Law,” Legal News. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Source: Legal research and analysis performed by Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton for Human Rights Watch, 2023-2024 and by researchers in the five regional divisions of Human Rights Watch.

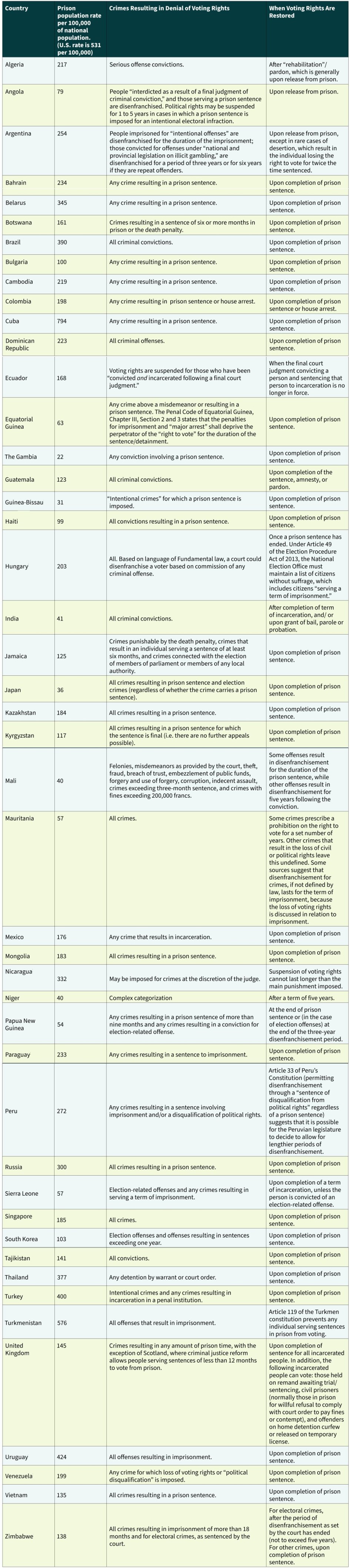

Countries that restrict the right to vote only while a person is in prison

The 46 countries in Table III disenfranchise people for a wider set of offenses than those in Table II but during incarceration only, which is similar to the disenfranchisement laws in 23 U.S. states.177

Table III. Forty-six Countries Deny Voting Rights Only During Term of Imprisonment

All country incarceration rates: World Prison Brief. “World Prison Brief Data”. Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research (ICPR), at Birkbeck, University of London. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

Government of Algeria. (2021). Electoral Law of Algeria, Article 52, 59, and 284. Retrieved May 10, 2024.

Government of Angola. (2004). Electoral Law of Angola, Articles 11, 12, and 178. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

Government of Argentina. (2021). Electoral Code of Argentina, Articles 3 and 5. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Bahrain. Bahrain Penal Code, Part III, Chapter 1, Articles 49 and 50, 1976. Bahrain, Law 14 of 2002 (“A person is prohibited from practicing political rights if he is sentenced for a crime or incarcerated, until he finishes his sentence.”).

Government of Belarus. Constitution of Belarus, Article 64. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Botswana. (2016). Botswana Constitution, Section 67(5) Retrieved May 15, 2024.; Botswana Elections Act, Sections 6(1)b and 6(2) Retrieved May 15, 2024.; Government of Botswana. (1986). Botswana Penal Code. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Brazil. (2017). Constitution of Brazil, Chapter IV, Article 15. Retrieved February 9, 2024; Brazil Supreme Electoral Court. Tribunal Superior Eleitoral. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

Government of Bulgaria. (1991). Constitution of Bulgaria, Article 42(1). Retrieved May 15, 2024.; Convention on Human Rights. (2016). The case of Kulinski & Sabev v Bulgaria. European Court of Human Rights. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Cambodia. (1997). Cambodia Law on Elections for Members of the Assembly, Article 50. United Nations Refugee Agency. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Colombia. (1986). The Electoral Code of Colombia. Article 70. Retrieved May 15, 2024.; CNN Español. (2022). “Pueden Votar Presos Elecciones Colombia,” CNN Latin America.

Cuba Constitution, Article 205; Electoral Law of Cuba, Article 8 (2019).

Government of Ecuador. (2021). Constitution of Ecuador, Article 64, Paragraph 2, 2008. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Equatorial Guinea. Penal Code of Equatorial Guinea, Chapter III, Section 2 and 3. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

Government of The Gambia. (1996). Electoral Act of The Gambia, Article 13(b). Retrieved May 17, 2024.

Government of Guatemala. Electoral Code of Guatemala, Articles 4 and 5. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

Government of Guinea-Bissau. (2019). Electoral Law of Guinea-Bissau, Article 9. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

Government of Haiti. (1985). Haiti Penal Code, Articles 9, 17, 18. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

Government of Hungary. The Fundamental Law of Hungary, Article XXXIII (6).

Government of India. The Representation of the People Act 1951, Section 62(5); Government of India. (1997). Anukul Chandra Pradhan vs Union of India & Ors., Supreme Court of India. Supreme Court of India.

Government of Jamaica.(2015). Constitution of Jamaica, Article 37(2). Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Japan. Public Offices Election Act of Japan, Article 11. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Kazakhstan. (1913). Kazakhstan Electoral Code, Article 4(a). Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Kyrgyzstan. (2011). Kyrgyzstan Electoral Code, Article 3(3). Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Mali. (2001). Penal Code of Mali, Article 6, Section 2, Article 8, Section 1. Retrieved May 15, 2024.; Government of Mali. (2013). Electoral Guide of Mali. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Mauritania. Penal Code of Mauritania, Articles 23 and 27.

Government of Mexico. (2015). Constitution of Mexico of 1917 with amendments, Article 38. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Mongolia. (2015). Electoral Code for the Election of President, Article 11.5. Retrieved May 15, 2024; Government of Mongolia. (2020). Electoral Code for the Election of the Legislature, Article 5.3. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Nicaragua. (2011). Penal Law of Nicaragua, Article 55 and 56. Retrieved May 15, 2024.; Government of Nicaragua. Constitution of Nicaragua, Art. 47. Retrieved May 15, 2024

Government of Niger. Electoral Code of Niger, Article 8; Penal Code of Niger, Articles 12, 38-40.

Government of Papua New Guinea. (2016). Constitution of Papua New Guinea, Article 50(1). Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Paraguay. (1996). Electoral Code, Article 91 (Law 834). Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Peru. (2021). Constitution of Peru, Article 33. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of the Russian Federation. Constitution of the Russian Federation, Chapter 2, Article 32.3. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Sierra Leone. (2022). Public Elections Act, Section 17(b)-(c), 2022. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Singapore. (1954). Singapore Parliamentary Elections Act (1954), Section 6(1A). Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of the Republic of Korea. (2016). Republic of Korea Public Official Elections Act, Article 18. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Tajikistan. Electoral Code of Tajikistan, Article 2.

Government of Thailand. (2017). Constitution of Thailand, Section 96. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Turkey. (2017). Criminal Code, Article 53. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Turkmenistan. (2016). Constitution of Turkmenistan, Article 119. Retrieved May 15, 2024.; Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. (2023). Parliamentary Elections in Turkmenistan, 2023. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of the United Kingdom. (1983). Representation of the People Act, United Kingdom, Section 3. Retrieved May 15, 2024; Johnston, N. (2023). Prisoners’ Voting Rights Research Briefing. United Kingdom Parliament. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Uruguay. Constitution of Uruguay, Article 80.

Government of Venezuela. (2015). Venezuela Penal Code, Articles 10, 16, 24. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Vietnam. (2015). Vietnam’s Law on Election of Deputies to the National Assembly and People’s Councils, Article 30, Section 1, 2. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

Government of Zimbabwe. (2013). Constitution of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe’s Constitution of 2013, Fourth Schedule. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Source: Legal research and analysis performed by Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton for Human Rights Watch, 2023-2024 and by researchers in the five regional divisions of Human Rights Watch. All country incarceration rates come from The World Prison Brief hosted by the Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research (ICPR), at Birkbeck, University of London, https://www.prisonstudies.org/world-prison-brief-data.

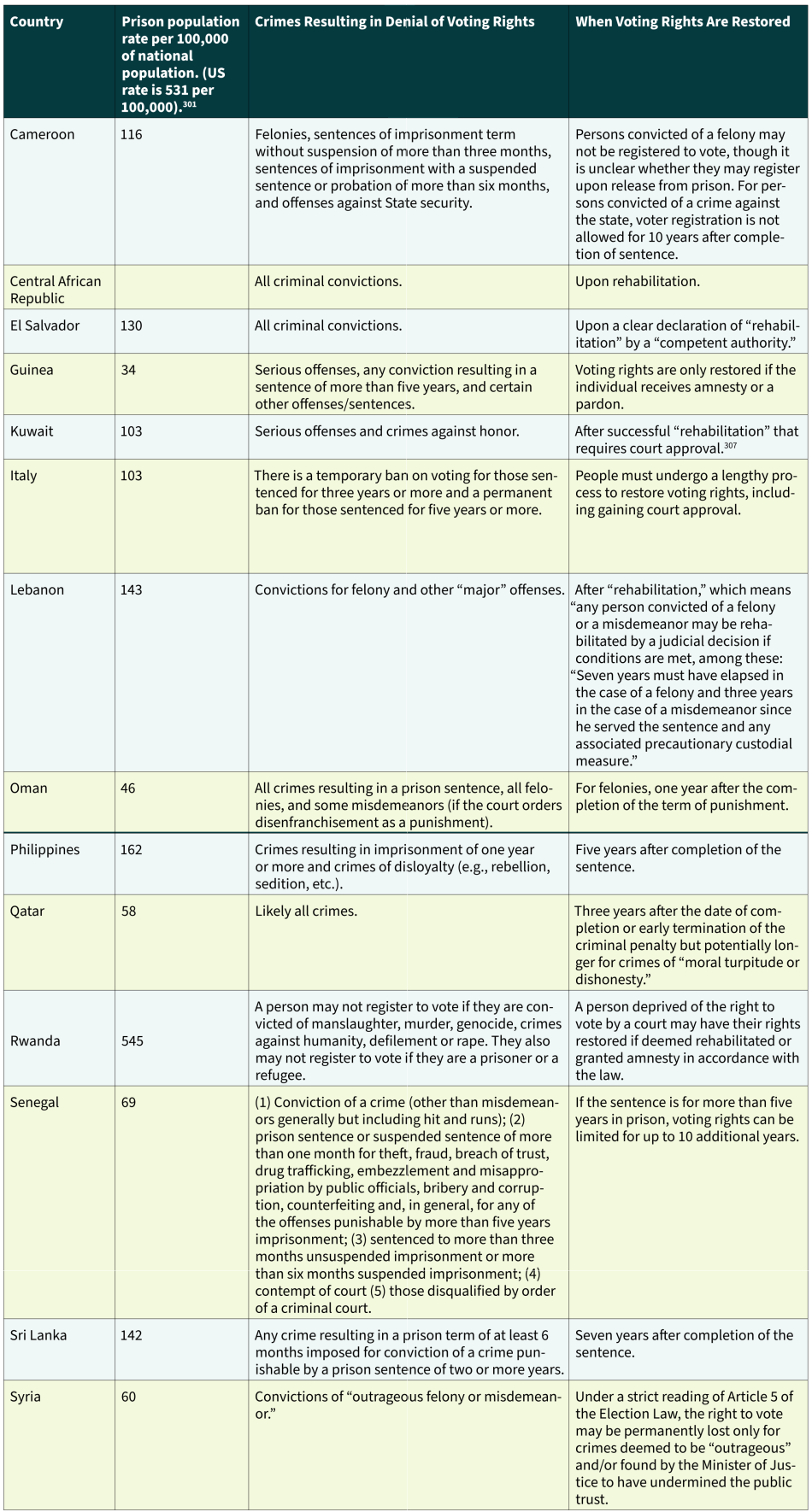

Countries that impose more far-reaching restrictions on voting rights

The 14 countries in Table IV disenfranchise people for a wider set of offenses than those in Table III, and the loss of voting rights continues for some period after incarceration – much like the disenfranchisement laws in 14 U.S. states.178

Table IV. Fourteen Countries Deny Voting Rights During Term of Imprisonment and Some Period Thereafter

All country incarceration rates: World Prison Brief. “World Prison Brief Data”. Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research (ICPR), at Birkbeck, University of London. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

Government of Cameroon. (2012). Electoral Code of Cameroon, Section 47. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of the Central African Republic. Electoral Code of the Central African Republic, Article 5.

Government of El Salvador. (1983, Amended 2003). Constitution of El Salvador, Articles 75 and 77. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Guinea. (2010). Electoral Code of Guinea, Article 7. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Kuwait News Agency. (2008). “Rehabilitation Is a Prerequisite for Exercising the Right to Vote for Convicts”.

European Court of Human Rights. (2012). Scopolla v. Italy,, Case Number 126/05. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Lebanon. (2017). Electoral Law of Lebanon, (Law Number 44), Article 4, 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Oman. Penal Act of Oman, Omani Penal Act, 2018, Article 58.

Government of Philippines. (1985). Omnibus Elections Code of Philippines, Section 118. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Qatar. Qatar Electoral Law, Article 3; Qatar Penal Code, Article 66.

Government of Rwanda. (2019). Rwanda Electoral Code, 2019, Articles 7 and 8. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Senegal. Penal Code, Article 29, Article 31, Article 34.

Government of Sri Lanka. (2023). Constitution of Sri Lanka, Article 89. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Government of Syria. (2014). General Elections Law of Syria, Article 5. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

Source: Legal research and analysis performed by Cleary, Gottlieb for Human Rights Watch, 2023-2024. All country incarceration rates come from The World Prison Brief hosted by the Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research (ICPR), at Birkbeck, University of London, https://www.prisonstudies.org/world-prison-brief-data.

Five countries impose permanent disenfranchisement

In five countries—the Republic of the Congo,179 Côte d’Ivoire,180 Madagascar,181 Morocco,182 and Togo183—people whose convictions fall in certain categories are disenfranchised permanently. These five countries are in the same category with the 11 U.S. states that permanently disenfranchise at least some people convicted of felonies.

Recent Global Trends to Expand and Protect Voting Rights

Several US states have enacted important reforms to protect voting rights, yet too many state legal systems still retain draconian disenfranchisement provisions that leave millions of people unable to vote. They are also lagging behind global trends. As reflected in the tables in the previous chapter of this report, many countries have taken significant steps in recent years to restore voting rights for people with criminal convictions. Even countries with legal systems that share an English common law heritage with the United States (such as Australia, Kenya, New Zealand, Uganda, and South Africa) have more comprehensively reformed their disenfranchisement laws than have the 50 US states when viewed as a whole. Although governments of some of the countries named below violate political rights in other ways or undermine free and fair elections—issues we are not addressing here–the countries are part of a discernible trend toward increased availability of voting rights for individuals with convictions in particular.

Ending criminal disenfranchisement

The Ugandan High Court in 2020 affirmed the constitutional right of all Ugandan citizens aged 18 and above, including incarcerated people, to vote. In reaching this conclusion, the Ugandan High Court cited reasoning expressed in a 1999 South African constitutional court ruling upholding the right to vote for all incarcerated people:

Universal adult suffrage on a common voter roll is one of the foundational values of our entire constitutional order…The universality of the franchise is important not only for nationhood and democracy. The vote of each and every citizen is a badge of dignity and personhood. Quite literally, it says that everybody counts. In a country of great disparities of wealth and power it declares that whoever we are, whether rich or poor, exalted or disgraced, we all belong to the same democratic South African nation; that our destinies are intertwined in a single interactive polity. Rights may not be limited without justification and legislation dealing with the franchise must be interpreted in favour of enfranchisement rather than disenfranchisement.184

In reliance in part on this reasoning, the Ugandan High Court ruled that all Ugandans can vote, regardless of conviction status.185 Uganda has not, however, consistently or fully implemented this directive.186

The pre-2016 constitution of Zambia had allowed its parliament to pass legislation that disqualified incarcerated people from voting. A landmark case (Godfrey Malembeka v. The Attorney-General and the Electoral of Zambia) in 2017 clarified that “the voting franchise is only restricted to age and not to the fact that a person is in lawful custody or has their freedom of movement restricted.”187 Though there are logistical impediments to voting in prison, many incarcerated people do exercise their right to vote in Zambia.188

Limiting the amount of time individuals are deprived of the right to vote

Some countries have changed their laws to limit the amount of time any individual is deprived of the right to vote.

For example, in 2014 Egypt repealed a sweeping law banning every person convicted of an offense from voting without time restrictions. The new law enacted in its place still enumerates a wide range of criminal convictions, among them: serious offenses, crimes of “moral turpitude,” and crimes of “corruption of political life,” that entail loss of voting rights for a set period of five years, irrespective of the sentence imposed. Nevertheless, the reform is in alignment with the view articulated by Egyptian human rights defender Negad El-Borai that the blanket denial of voting rights for every person was extreme: “I think prison [in terms of punishment] is enough.”189

The Philippines used to permanently disenfranchise individuals sentenced to a prison sentence of one year or longer, but in a series of amendments since the early-2000s has amended the law to allow for the reinstatement of voting rights five years following the completion of an individual’s sentence.

Since 1994, judges in France may impose a maximum 5-year limit on the right to vote for “délit” (roughly equivalent to misdemeanors in US law) convictions, while “crime” (roughly equivalent to felonies in US law) convictions may result in a maximum ten-year ban. According to France’s justice ministry, in the 2022 presidential election, more than 10,000 incarcerated people voted under new rules allowing incarcerated people in France to vote by mail.190

Narrowing the types of convictions that can lead to disenfranchisement

Still other countries have narrowed the categories of criminal convictions or sentences that can trigger disenfranchisement. For example, in the Netherlands, voting rights for people with criminal system contacts have been expansive for some time. A legal change in 1983 narrowed the ability of judges to sentence individuals to loss of voting rights only when they are convicted of crimes against the state and election-related crimes. As of 2017, according to media reports, only fifty-six individuals lost their right to vote due to criminal convictions.191