Still Cruel and Unusual: Extreme Sentences for Youth and Emerging Adults

Despite a wave of reforms across America that reduce the use of juvenile life without parole sentences, thousands of youth and emerging adults have been left behind even though their sentences are essentially the same.

Related to: Sentencing Reform, Youth Justice, Incarceration, Racial Justice

A wave of reforms since 2010 has changed the trajectory of punishment for young people by substantially limiting the use of juvenile life without parole (JLWOP) sentences. At the sentence’s height of prominence in 2012, more than 2,900 people were serving JLWOP, which provided no avenue for review or release.1 Since reforms began, most sentence recipients have at least been afforded a meaningful opportunity for a parole or sentence review. More than 1,000 have come home.2

This progress is remarkable, yet thousands more who have been sentenced to similarly extreme punishments as youth have not been awarded the same opportunity. Our analysis shows that in 2020, prisons held over 8,600 people sentenced for crimes committed when they were under 18 who were serving either life with the possibility of parole (LWP) or “virtual” life sentences of 50 years or longer. This brief argues for extending the sentencing relief available in JLWOP cases to those serving other forms of life imprisonment for crimes committed in their youth.

In addition, The Sentencing Project has estimated that nearly two in five people sentenced to life without parole (LWOP) were 25 or younger at the time of their crime.3 These emerging adults, too, deserve a meaningful opportunity for a second look because their developmental similarities with younger people reduces their culpability in criminal conduct. The evidence provided in this brief supports bold reforms for youth and emerging adults sentenced to extreme punishments.

Supreme Court of the United States Authorizes Second Looks for Young People

A series of landmark U.S. Supreme Court cases beginning in 2010 acknowledged that children under 18 must be viewed as less culpable for criminal conduct compared to adults because they have not yet fully developed. Their reduced culpability stems from the increase in risk-taking and impulsivity during this period of brain development, particularly in emotionally charged situations.4 Beginning with Graham v. Florida in 2010,5 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that individuals under 18 could not receive LWOP in non-homicide crimes. This ruling affected the sentences of less than 200 people,6 but the implications of the ruling set precedence for future cases that elicited the resentencing and subsequent release of many more.7

In 2012, the Court ruled in Miller v. Alabama that individuals under 18 could not be sentenced to LWOP in states that uphold a mandatory LWOP statute for homicide convictions because there could be no guarantee that young age and its attending characteristics had been accounted for.8 The Miller ruling had much broader implications than the Graham ruling. Research conducted by The Sentencing Project confirmed that prior to Miller, the majority of JLWOP sentences were imposed in states where judges did not have another choice.9 This ruling was not explicitly retroactive, however. In 2016 in Montgomery v. Louisiana,((Montgomery v. Louisiana, 577 U.S. 190 (2016). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/577/190/)) the Court affirmed that the Miller ruling applied retroactively, affecting over 2,000 individuals previously sentenced to JLWOP.10 A 2024 study led by researchers at the University of California Los Angeles, found that 87% of the JLWOP population has been resentenced following the rulings in Miller and Montgomery. As of January 2024, 1,070 individuals have been released.11

Legislative Momentum Toward Abolishing Life without Parole for Juveniles

Figure 1. Chronology of State JLWOP Bans

The Supreme Court’s rulings propelled a growing number of states to ban JLWOP sentences altogether, reflecting a significant shift in precedent and interpretation of the Eighth Amendment’s protection against cruel and unusual punishments.12 As depicted in Figure 1, only three states had excluded individuals under 18 from receiving parole-ineligible life sentences when Miller was decided: Alaska, Kansas, and Kentucky. After the Miller ruling, an additional nine states banned JLWOP: Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Nevada, Texas, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming. After the court’s Montgomery v. Louisiana ruling in 2016, an additional 16 states and the District of Columbia banned JLWOP.13 This brought the total of states that ban LWOP for juveniles to 29, including Washington, DC. Several additional states have introduced, but not yet passed, legislation reforms to ban JLWOP as a sentencing option.14 Despite inconsistency and delay by certain states regarding implementation of the supreme court’s mandate, it is rare to observe such rapid reform overall. Even so, there remain thousands of individuals who are serving long or life sentences in states who do not qualify for a second look because their sentence was not technically (i.e., statutorily) life without parole or because they were 18 or older at the time of the offense. This occurs when reforms are limited to narrowing or banning JLWOP specifically, rather than embracing a broader, more accurate, definition of life imprisonment for youth and adolescents.

The Sentencing Project conducted groundbreaking survey research in 2011 that provided life histories of nearly 1,600 people who were serving JLWOP.15 Trauma and violence accompanied their childhoods; their stories disclosed that before they victimized others, they had been victimized.16 Table 1 provides an overview of these findings. This research served as critical to understanding the commonality of significant trauma experienced by these individuals. While tragic circumstances do not excuse criminal acts, such research illuminates missed opportunities for intervention.

| Topic | Percent “Yes” |

|---|---|

| Witnessed violence at home | 79 |

| Victim of a violent crime | 71 |

| Drugs were sold openly in their neighborhood | 71 |

| Did not consider their neighborhood safe from crime | 63 |

| Saw violence in their neighborhood at least once a week | 54 |

| Experienced physical abuse at home | 47 |

| Experienced sexual abuse at home | 11 |

Maryland’s Juvenile Restoration Act (JRA) represents an innovative approach to JLWOP reform.17 Enacted in 2021, this law authorizes a review of all sentences exceeding 20 years for individuals who were under 18 at the time of their crime, and allows resentencing opportunities for all extreme sentences. At the time of the Montgomery decision, Maryland had reported two dozen people serving JLWOP and 400 individuals serving juvenile life with parole (JLWP) or virtual life sentences.18 By extending the benefits of the reform to all extreme sentences, rather than limiting it to LWOP, the JRA has significantly impacted those serving long and life sentences in Maryland. According to the Maryland Office of the Public Defender’s 2022 report,19 the JRA prompted the release of 23 individuals from prison who were serving long or life sentences in Maryland. The legislation supported the reduction of sentence in four additional cases, but these individuals were required to serve additional time in prison prior to their release.

Life with Parole and Virtual Life Sentences Still Widely Used for Youth Under 18

The Sentencing Project has examined state-level data regarding people serving sentences of life with parole (LWP) and sentences that are as much as 50 years or more before parole review (i.e., virtual life, or VL).20 In 2020, we found a total of 8,632 individuals serving such sentences for crimes committed as minors.21 The populations were especially large in California (2,358), Georgia (900), Texas (1,081), and New York (461). Combined, these four states accounted for over half the total population of people sentenced as youth to parole-eligible life or virtual life sentences. In Georgia, children as young as 14 when they were charged are among the state’s 900 individuals serving these life sentences.22 In this state, a mandatory minimum of 30 years is required in most cases before one’s initial parole consideration.23

Table 2 shows the total number of people serving life with parole (LWP) and virtual life sentences (VL) at the start of 2020 for crimes committed when they were under 18. All but two states report persons serving life and virtual life sentences for crimes as juveniles. In four states—Georgia, Louisiana, Massachusetts, and Mississippi—more than 10% of the total population of people with parole-eligible life or virtual life sentences were under 18 at the time of their crime.

| State | LWP and VL Sentences by Individuals Under 18 | LWP and VL Sentences by Individuals Under 18, as Percent of Total LWP and VL Population |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 55 | 1.30% |

| Alaska | 2 | 0.50% |

| Arizona | 136 | 6.70% |

| Arkansas* | 95 | 5.70% |

| California* | 2,358 | 6.60% |

| Colorado* | 86 | 2.90% |

| Connecticut* | 46 | 6.80% |

| Delaware | 13 | 4.10% |

| Florida | 341 | 7.30% |

| Georgia | 900 | 10.60% |

| Hawaii | 4 | 1.30% |

| Idaho | 8 | 1.50% |

| Illinois* | 16 | 0.60% |

| Indiana | 77 | 2.00% |

| Iowa | 74 | 9.10% |

| Kansas | 77 | 5.30% |

| Kentucky | 16 | 1.30% |

| Louisiana* | 200 | 12.30% |

| Maryland* | 314 | 9.30% |

| Massachusetts* | 139 | 13.40% |

| Michigan | 137 | 7.70% |

| Minnesota* | 34 | 7.10% |

| Mississippi | 92 | 10.70% |

| Missouri* | 145 | 6.20% |

| Montana | 3 | 2.80% |

| Nebraska | 59 | 8.30% |

| Nevada* | 114 | 4.80% |

| New Hampshire | 11 | 6.30% |

| New Jersey | 19 | 1.20% |

| New Mexico* | 39 | 4.90% |

| New York | 461 | 5.80% |

| North Carolina | 250 | 9.60% |

| North Dakota | 3 | 6.10% |

| Ohio* | 331 | 4.30% |

| Oklahoma | 49 | 1.80% |

| Oregon* | 16 | 1.90% |

| Pennsylvania | 115 | 4.00% |

| Rhode Island* | 3 | 1.40% |

| South Carolina | 103 | 8.40% |

| South Dakota | 8 | 3.70% |

| Tennessee | 238 | 9.40% |

| Texas | 1,081 | 6.30% |

| Utah* | 63 | 2.90% |

| Vermont | 1 | 0.70% |

| Virginia** | 85 | 3.30% |

| Washington* | 69 | 2.70% |

| Wisconsin | 140 | 9.90% |

| Wyoming | 6 | 2.00% |

| Total | 8,632 | 5.90% |

Source: Data were obtained from individual state departments of corrections in 2020. Maine and West Virginia do not report any individuals serving LWP or virtual life for crimes committed when under 18.

* = These states have recently enacted reforms that extend JLWOP bans to other extreme sentences which affect some or all LWP or VL sentences, depending on the statute. For instance, in 2021, Virginia enacted a law to allow parole review for all persons who were under 18 at the time of their crime and have served 20 years. The state’s legislative analysis predicts that a total 720 individuals, including those noted in the table above, qualify for reforms under this Act. For a complete list, see Feldman, B. (2024). The second look movement: A review of the nation’s sentence review laws. The Sentencing Project. Appendix I. The Sentencing Project.

Despite the reality that people “age out” of criminal activity as they approach adulthood,24 jurisdictions impose lengthy and life sentences for young people under the misconception that long sentences serve a deterrent, rehabilitative, or retributive function. Yet recidivism among those resentenced and released from life sentences is rare.25

Many of the 8,600 individuals identified in Table 2 have already served decades in prison beyond their risk to public safety. In most instances, the underlying crimes were serious: over three quarters were convicted of a homicide and 8% were convicted of a rape or sexual assault. Twelve percent of those serving parole-eligible life or a virtual life sentence were convicted for assaults and robberies. Drug and property crimes were among the least represented offenses, but 57 individuals were serving life with parole or virtual life sentences for these nonviolent crimes.

Race

An abundance of evidence shows that Black Americans receive harsher sentencing outcomes than whites across the sentencing spectrum, from the initial decision of whether to incarcerate to the length of sentence imposed.26 Recent research has noted that racial disparities are especially extreme for lengthier sentences.27 Black people make up 53% of young people sentenced to LWP and virtual life sentences. In the following states, at least 80% of people serving these sentences are Black: Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, and Mississippi. Disproportionality is not limited to states in the south: in Indiana, all five people serving life with the possibility of parole are Black. In Wisconsin half of the youth serving life with parole are Black.

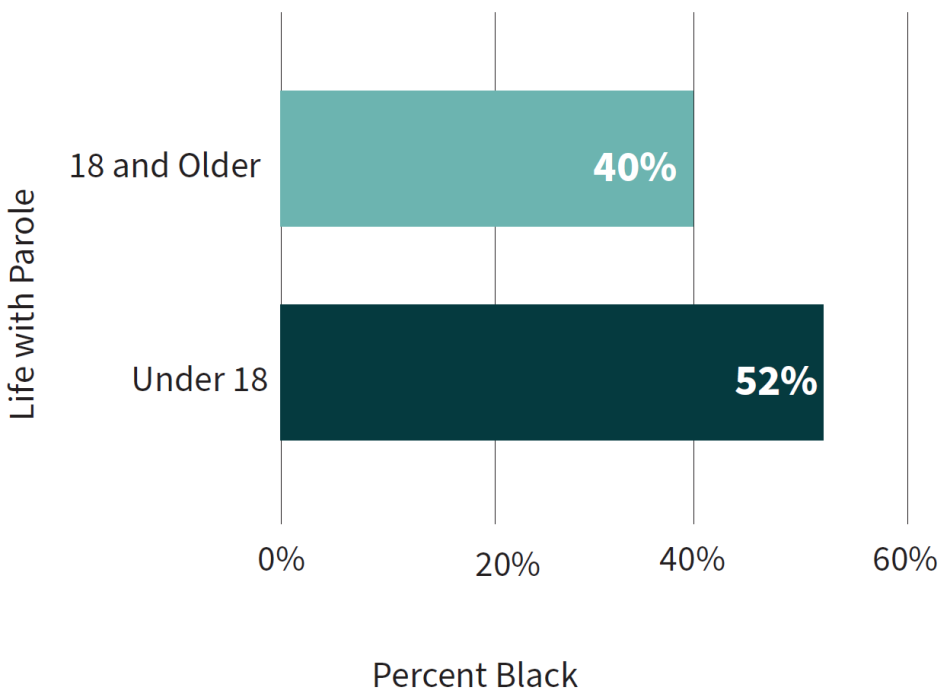

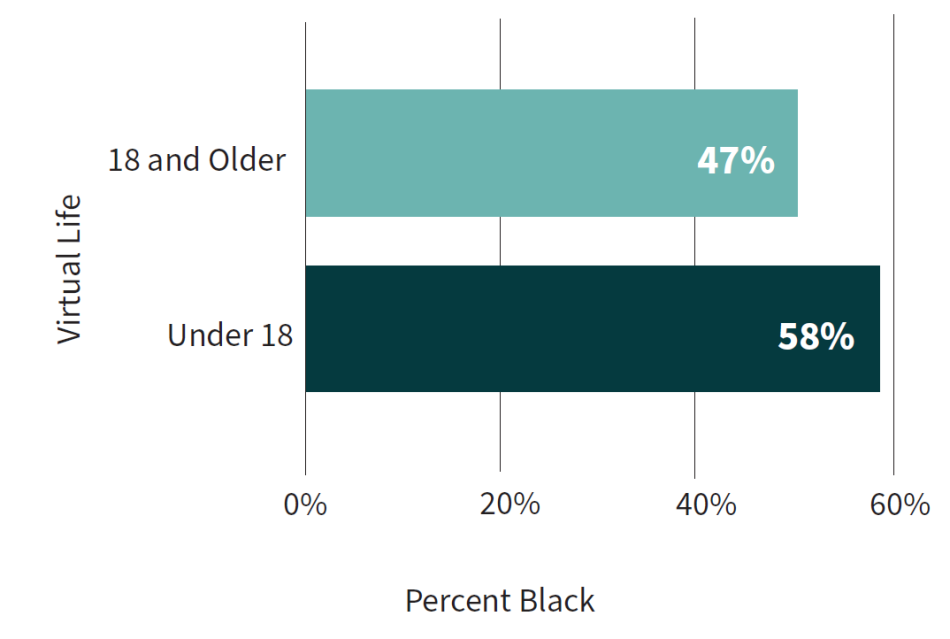

When looking at the racial composition of people serving LWP and virtual life sentences, these statistics reveal that Black youth are disproportionately represented in the population of those serving these severe sentences, compared to Black adults. Figures 2 and 3 show that 40% of adults serving life-with-parole sentences are Black, compared with 52% juveniles who are Black. Similarly, while 47% of people 18 and older who are serving virtual life sentences are Black, 58% of juveniles serving virtual life sentences are Black.

Figure 2. Race, Juvenile Status, and Life with Parole Sentences

Figure 3. Race, Juvenile Status, and Virtual Life Sentences

Life Sentences Still Widely Imposed on Emerging Adults

A broad range of experts across the fields of neuroscience, sociology, and psychology agree that juvenile and emerging adult defendants share similarities in their reduced culpability and developmental immaturity.28 Cognitive, emotional, and physical developments occurring between the ages of 18 and 25 or even later are consequential to behavior. As such, emerging adults have maturity levels more like individuals under 18 than those who have fully developed into adulthood.29

To explore the population of emerging adults further, The Sentencing Project examined state-level sentencing data of 30,000 individuals sentenced to life without parole (LWOP) between 1995 and 2017.30 Here we found that two in five individuals sentenced to LWOP had been 25 or younger at the time of their conviction. In Pennsylvania and Michigan, half of the LWOP population falls in the category of emerging adults. Overall, the peak age at conviction for people sentenced to LWOP is 23 years old. This is a critical finding, since this age falls well within the standard boundaries of emerging adulthood.

Additionally, being Black and young produced a substantially larger share of LWOP sentences than being Black alone: two thirds (66%) of emerging adults sentenced to LWOP were Black. Among people sentenced to LWOP in adulthood, 51% are Black. Though we cannot make causal connections from these data alone, racism clearly plays a role in Black people’s experience of the criminal legal system from start to end.

Expanding Reforms to Emerging Adults

As awareness of the diminished psychological capacity of emerging adults increases, more than a dozen states have introduced or implemented reforms to protect emerging adults from some punishments that would be unduly harsh given their stage of development.31 Some reforms extend to those serving life sentences. In 2019, the Illinois legislature voted to allow parole review at 10 or 20 years into a sentence for most crimes, exclusive of LWOP sentences, if the individual was under 21 at the time of the offense.32 Those going before a parole board now have a right to an attorney and at least one member of the board must hold expertise on the issue of adolescent development. In its review process, the parole board is required to give great weight to the hallmark features of youth and subsequent growth in making its parole decision. Unfortunately, the law does not apply retroactively.

Also in Illinois, the legislature moved to end LWOP for individuals under 21 years old in most instances, permitting review after 40 years. Though the law is not retroactively applied, reforms are underway to remedy this. If successful, the reform would allow the possibility of eventual release of as many as 3,000 people.

In January 2024, the supreme court of Massachusetts ruled in Mattis v. Commonwealth that life without parole sentences for those who were between 18 and 20 would violate the state’s constitutional protections against cruel or unusual punishments.33 This ruling extended the court’s previous decision in Diatchenko v. Massachusetts, which banned LWOP for persons who were under 18 at the time of the crime. Basing arguments on the latest understanding of emerging adulthood, lawyers for Mr. Mattis successfully argued that older adolescents share markers of neurobiological maturity more like younger adolescents rather than adults.

In California, individuals whose crime occurred when they were between 18 and 26 are classified as “youthful offenders” and, with the exception of LWOP sentences, are afforded a specialized parole review within 15-25 years, depending on age at offense.

In 2024, Washington’s highest court rendered a favorable ruling in State v. Monschke.34 This case tested whether LWOP was appropriate for persons under 20 years old. The court determined that mitigating qualities of youthfulness for people under 20 demanded a new sentence.35

In 2022, a Michigan appellate court ruled, in the case of People v. Parks, that it is unconstitutional to sentence 18-year-old defendants convicted of first-degree murder to life without parole. Citing neurological research in its ruling, the court held that the state constitution “prohibits imposing sentences of mandatory life without parole for 18-year-old defendants convicted of first-degree murder, given that their neurological characteristics are identical to those of juveniles.”36

Conclusion

The Sentencing Project continues to advocate for the resentencing of youth and emerging adults with LWOP sentences, understanding that lengthy prison sentences ignore the fact that most people who commit crime, even those who have committed a series of crimes, age out of criminal conduct. Dozens of empirical studies reflect the fact that people are most at-risk for committing crime in the late teenage years to their mid-twenties, which is consistent with neurodevelopmental brain science.37

The Sentencing Project plays a crucial role in educating the public and policymakers about the alarming trend of extreme sentences for crimes committed in youth. As policymakers design reforms for the criminal justice system, these changes should align with neurobiological research and encompass all forms of life imprisonment and extreme sentences. Youth and emerging adults who committed crimes during adolescence should receive a sentence review within the first ten years, with a rebuttable presumption of release after fifteen years.38 This recommendation stems from decades of observing the ineffectiveness of severe punishments, as social science consistently shows that extreme penalties offer little public safety benefit.

| 1. | Bennett, J.Z., Brydon, D.M., Jeffrey T. Ward, J.T., Jackson, D.B., Ouellet, L., Turner, R., & Abrams, L. (2024). In the wake of Miller and Montgomery: A national view of people sentenced to juvenile life without parole. Journal of Criminal Justice, 93, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2024.102199. This research draws from The Sentencing Project’s existing research including a national tracking effort of those sentenced to JLWOP prior to the 2012 Miller and 2016 Montgomery rulings. |

|---|---|

| 2. | 2 Bennett, J.Z., Brydon, D.M., Jeffrey T. Ward, J.T., Jackson, D.B., Ouellet, L., Turner, R., & Abrams, L. (2024), see note 1. |

| 3. | Nellis, A. & Monazzam, N. (2023). Left to die in prison: Emerging adults 25 and younger sentenced to life without parole. The Sentencing Project. This study examined sentences in 20 states between 1995 and 2017, representing nearly 30,000 individuals sentenced to LWOP, 11,600 of whom were under 26 years old at sentencing. |

| 4. | Bigler, E. (2021). Charting brain development in graphs, diagrams, and figures from childhood, adolescence, to early adulthood: Neuroimaging implications for neuropsychology. Journal of Pediatric Neuropsychology, 7(1-2), 27–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40817-021-00099-6. |

| 5. | Graham v. Florida, 560 U.S. 48 (2010). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/560/48/ |

| 6. | Schab, E., Annino, P., & Nellis, A. (2014) Miller resentencing project report: Florida juveniles sentenced to mandatory life without parole. FSU College of Law, Public Law Research Paper No. 662.https://ssrn.com/abstract=2374429. |

| 7. | Feldman, B. (2024). The second look movement: A review of the nation’s sentence review laws. The Sentencing Project. |

| 8. | Miller v. Alabama, 567 U.S. 460 (2012).https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/567/460/ |

| 9. | Nellis, A. (2015). A return to justice: Rethinking our approach to juveniles in the system. Rowman & Littlefield. |

| 10. | Bennett, J.Z., Brydon, D.M., Jeffrey T. Ward, J.T., Jackson, D.B., Ouellet, L., Turner, R., & Abrams, L. (2024), see note 1. |

| 11. | Bennett, J.Z., Brydon, D.M., Jeffrey T. Ward, J.T., Jackson, D.B., Ouellet, L., Turner, R., & Abrams, L. (2024), see note 1. |

| 12. | Rovner, J. (2023). Juvenile life without parole: An overview. The Sentencing Project. |

| 13. | The 16 states are: Arkansas (2017), California (2017), Colorado (2016), Iowa (2016), Illinois (2023), Maryland (2021), Minnesota (2023), New Jersey (2017), New Mexico (2023), North Dakota (2017), Ohio (2021), Oregon (2019), South Dakota (2016), Utah (2016), Virginia (2020), Washington (2018). Washington DC also banned JLWOP (2017). |

| 14. | In 2024, such bills were introduced in Georgia, Michigan, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Wisconsin. |

| 15. | Nellis, A. (2012). The lives of juvenile lifers: Findings from a national survey. The Sentencing Project. |

| 16. | Nellis, A. (2012), see note 16. |

| 17. | Maryland Juvenile Restoration Act, https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/2021RS/bills/sb/sb0494E.pdf. |

| 18. | Nellis, A. (2021). No end in sight: America’s enduring reliance on life imprisonment. The Sentencing Project. |

| 19. | Maryland Office of the Public Defender. (2022). The juvenile restoration act: Year one – October 1, 2021 to September 30, 2022. https://opd.state.md.us/_files/ugd/868471_e5999fc44e87471baca9aa9ca10180fb.pdf |

| 20. | We obtained data from individual departments of corrections through public records requests to produce this analysis. |

| 21. | Nellis, A. (2021), see note 19. |

| 22. | Nellis, A. (2021), see note 19. |

| 23. | Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles (n.d.) Life Sentences | State Board of Pardons and Paroles. Georgia’s “seven deadly sins” that require 30 years before consideration include: armed robbery, kidnapping, rape, murder, aggravated sodomy, aggravated sexual battery, and aggravated child molestation. See, Ghandnoosh, N. (2017). Delaying a second chance: The declining prospects for parole on life sentences. The Sentencing Project. |

| 24. | Dozens of studies find that the typical ages at which people are most likely to engage in violence climb from the late teenage years to one’s twenties before dramatically falling throughout one’s mid-to late-twenties. The “age-crime” curve refers to the rapidly declining likelihood to commit crime, including violent crime, with age. |

| 25. | Daftary-Kapur, T., & Zottoli, T. (2020). Resentencing of juvenile lifers: The Philadelphia experience. https://digitalcommons.montclair.edu/justice-studies-facpubs/84. Research conducted by Montclair University’s Tarika Daftary-Kapur and Tina Zottoli found that recidivism rates were 1.14% for individuals resentenced and released from original JLWOP sentences in Philadelphia, an area that once housed the largest population of juveniles sentenced to LWOP. See also, Nellis, A., Bishop, B., & Liston, S. (2021). A New Lease on Life. The Sentencing Project. |

| 26. | Ghandnoosh, N., Berry, C., & Trinka, L. (2023). One in five: Racial disparity in imprisonment, causes and remedies. The Sentencing Project. |

| 27. | Ghandnoosh, N., Berry, C., & Trinka, L. (2023), see note 27; Ghandnoosh, N., Nellis, A. (2022). How many people are spending over a decade in prison? The Sentencing Project; Muhammad, K. G., Western, B., Negussie, Y., & Backes, E. (Eds.) (2022). Reducing racial inequality in crime and justice: science, practice, and policy. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26705/reducing-racial-inequality-in-crime-and-justice-science-practice-and |

| 28. | Hannan, K. R., Cullen, F. T., Graham, A., Lero Jonson, C., Pickett, J. T., Haner, M., & Sloan, M. M. (2023). Public support for second look sentencing: Is there a Shawshank redemption effect? Criminology and Public Policy, 22(2), 263-292. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12616. |

| 29. | Bigler, E. (2021). Charting brain development in graphs, diagrams, and figures from childhood, adolescence, to early adulthood: Neuroimaging implications for neuropsychology. Journal of Pediatric Neuropsychology, 7(1-2), 27–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40817-021-00099-6; Tabashneck, S., Shen, F. X, Edershim, J. G., & Kinscherff, R. T. (2022). The science of late adolescence: A guide for judges, attorneys and policy makers. Center for Law, Brain & Behavior at Massachusetts General Hospital. https://clbb.mgh.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/CLBB-White-Paper-on-the-Science-of-Late-Adolescence-3.pdf; Aamodt, S., & Wang, S. (2011). Welcome to your child’s brain: how the mind grows from conception to college. American Psychological Association. |

| 30. | Nellis, A. & Monazzam, N. (2023), see note 3. |

| 31. | Feldman, B. (2024), see note 7. |

| 32. | H.B. 531, 102nd Gen. Assembly, (Illinois, 2019) (enacted). |

| 33. | Commonwealth v. Mattis, 28 U.S.C. § 2254 (Mass. 2023). https://caselaw.findlaw.com/court/ma-supreme-judicial-court/115703895.html. |

| 34. | State v. Monschke, 133 Wn. App. 313, 318 (Wash. Ct. App. 2006). https://caselaw.findlaw.com/court/wa-court-of-appeals/1197904.html |

| 35. | Kimonti Carter was convicted of aggravated murder at 18 years old and sentenced to mandatory life without parole. The Monschke ruling, invalidating mandatory LWOP sentences for individuals under 21 years old, created a pathway for Carter to be resentenced. In 2022 he was sentenced to 280 months and released after 25 years in prison. The state appealed his release, arguing that the court did not have the authority to resentence him and that life with the possibility of parole would have been the correct result of Carter’s resentencing. On May 23, 2024, the Washington State Supreme Court rejected an effort to send Carter back to prison. |

| 36. | People v. Parks, 510 Mich. 225, 233 (Mich. 2022). https://casetext.com/case/people-v-parks-2073. |

| 37. | Nellis, A., Bishop, B., & Liston, S. (2021). See Note 28. The Sentencing Project. |

| 38. | Komar, L., Nellis, A., & Budd, K. (2023). Counting down: Paths to a 20-year maximum prison sentence. The Sentencing Project. |