A Matter of Life: The Scope and Impact of Life and Long Term Imprisonment in the United States

One in six people in prison – nearly 200,000 people nationwide – are serving life sentences. This comprehensive 50-state report examines the prevalence and implications of life sentences across the country, highlighting the disproportionate impact of such extreme sentences on people of color and the inefficacy of punitive measures in improving community safety.

Related to: Sentencing Reform, Incarceration, Racial Justice

Overview

In the United States, the federal government and every state enforces sentencing laws that incarcerate people for lengths that will exceed, or likely exceed, the span of a person’s natural life. In 2024, almost 200,000 people, or one in six people in prison, were serving life sentences.1 The criminal legal system’s dependence on life sentences disregards research showing that extreme sentences are not an effective public safety solution.

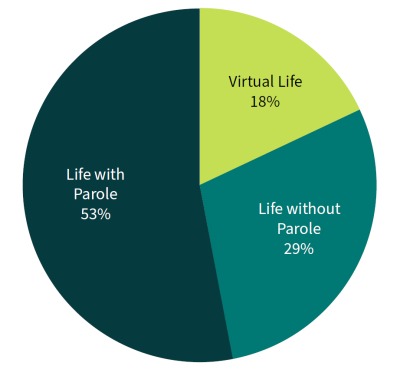

This report represents The Sentencing Project’s sixth national census of people serving life sentences, which includes life with the possibility of parole; life without the possibility of parole; and virtual life sentences (sentences reaching 50 years or longer). The report finds more people were serving life without parole (LWOP) in 2024 than ever before: 56,245 people were serving this “death by incarceration” sentence, a 68% increase since 2003. While the total number of people serving life sentences decreased 4% from 2020 to 2024, this decline trails the 13% downsizing of the total prison population. Moreover, nearly half the states had more people serving a life sentence in 2024 than in 2020.

The large number of people serving life sentences raises critical questions about moral, financial, and justice-related consequences that must be addressed by the nation as well as the states. We believe the findings and recommendations documented in this report will contribute to better criminal legal policy decisions and a more humane and effective criminal legal system.

Key National Findings

- One in six people in U.S. prisons is serving a life sentence (16% of the prison population, or 194,803 people)—a proportion that has reached an all-time high even as crime rates are near record lows.

- The United States makes up roughly 4% of the world population but holds an estimated 40% of the world’s life-sentenced population, including 83% of persons serving LWOP.

- More people are serving life without parole in 2024 than ever: 56,245 people, a 68% increase since 2003.

- Despite a 13% decline in the total reported prison population from 2020 to 2024, the total number of people serving life sentences decreased by only 4%.

- Nearly half of people serving life sentences are Black, and racial disparities are the greatest with respect to people sentenced to life without parole.

- A total of 97,160 people are serving sentences of life with parole.

- Life sentences reaching 50 years or more, referred to as “virtual life sentences,” account for 41,398 people in prison.

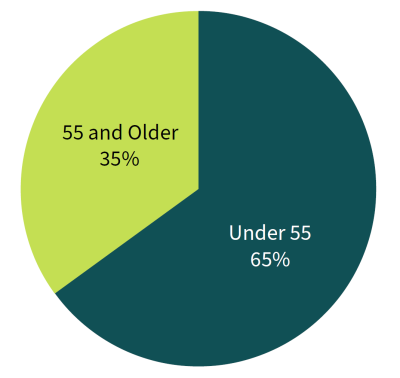

- Persons aged 55 and older account for nearly two-fifths of people serving life.

- One in every 11 women in prison is serving a life sentence.

- Almost 70,000 individuals serving life were under 25—youth and “emerging adults”—at the time of their offense.2 Among these, nearly one-third have no opportunity for parole.

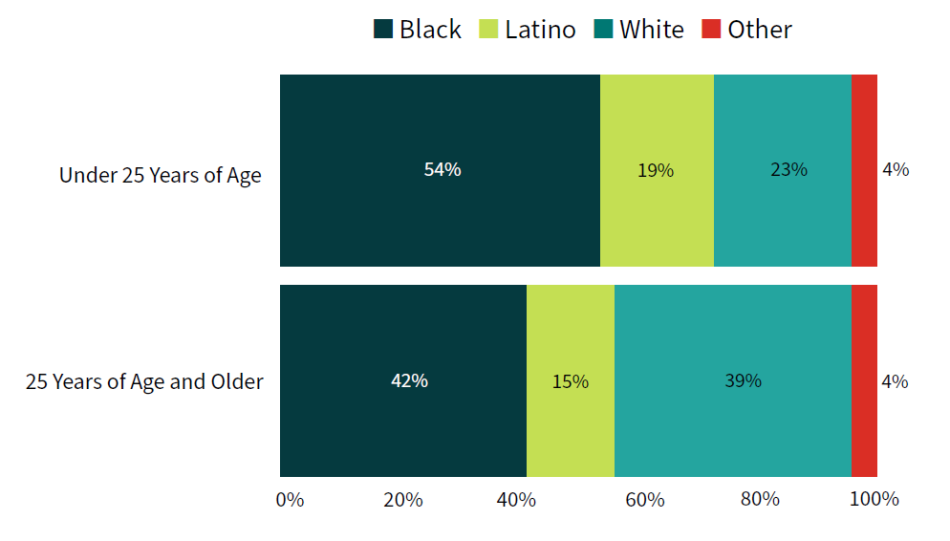

- Racial disparities in life imprisonment are higher among those who were under 25 at the time of their offense compared to those who were 25 and older.

Key Jurisdictional Findings

- More than half the states increased their life without parole (LWOP) populations in the past four years. The number of people serving LWOP is highest in Florida (10,915), California (5,111), Pennsylvania (5,059), Louisiana (3,900), and Michigan (3,551); these five states combined account for half the people serving LWOP nationwide.

- The 1.2% increase in the LWOP population nationally includes notable decreases in the following states and in the federal system:

- Louisiana (⬇ 473 people)

- Michigan (⬇ 331 people)

- Pennsylvania (⬇ 316 people)

- Federal (⬇ 452 people)

- In seven states—Alabama, California, Colorado, Georgia, Massachusetts, Montana, and Utah—more than one in four Black people in prison is serving a life sentence.

- Thirty-five states and the federal government reported fewer people in 2024 serving life with parole (LWP) compared to 2020. Notable decreases in this population occurred in these states:

- California (⬇ 3,765 people)

- New York (⬇ 1,404 people)

- Nevada (⬇ 410 people)

- Michigan (⬇ 401 people)

- States that rely heavily on virtual life sentences are led by Indiana, with 16% of its prison population—nearly 4,000 people—serving virtual life. In Alaska, Montana, Nebraska, and Tennessee, 10% or more of those in prison are serving virtual life terms.

- In Michigan, 56% of the total life-sentenced population are age 55 or older; three-quarters of the 55 and over population are serving LWOP.

Recommendations

- Abolish life without parole (LWOP) sentences. LWOP sentences ignore the rehabilitation of individuals who have changed over time; as such, LWOP sentences deny a person’s humanity and are cruel, in addition to being ineffective.

- Cap imprisonment at 20 years for crimes committed by adults, except for unusual circumstances, and at 15 years for youth and emerging adults.

- Extend juvenile sentencing protections to emerging adults in acknowledgment of their ongoing cognitive development and reduced culpability.

- Institute an automatic sentence review process, or second-look mechanism, within 10 years of imprisonment, which includes a rebuttable presumption of resentencing.

- Revamp parole boards and reform the parole process to accelerate parole reviews for people serving long-term sentences. An increase in transparency and expertise among parole board members will lead to fairer decisions focused on assessing personal transformation and promoting community safety.

- End stacked sentences. Consecutive prison sentences that effectively serve as life terms are as problematic as statutorily defined life sentences. Such sentences can obscure the extensive burden that lengthy imprisonment terms place on the prison system, and contribute to the expansion of mass incarceration and its racial disparities.

Introduction

Life imprisonment in the United States is a deeply flawed and ineffective tool for crime control, one that fails to deliver on promises of community safety while disproportionately harming communities of color, especially Black Americans. Unlike many other nations, where life sentences are rare and of a shorter duration,3 the United States has embraced life sentences at alarming rates over the past four decades with little regard for fairness or justice. Far from reducing crime, life imprisonment reflects a punitive mindset that prioritizes retribution over rehabilitation, with devastating consequences for individuals and for society.4

The central point of life sentences is the idea that making punishments more severe will reduce criminal behavior. But as explained below, the reality is that the mainstream use of life sentences deprives people of dignity, fails as a useful deterrent, incapacitates people who have aged out of criminal activity, and diverts public resources from more effective crime prevention policies. These facts should compel decision-makers to eliminate this punishment entirely.

Today’s responses to crime exploit public fears and rely on harmful, thinly veiled racist stereotypes.5 While crime is a common worry, concerns are often inflated beyond actual risk, and many people believe that crime rates are far higher than is actually the case. Instead of focusing on educating the public and providing accurate information, many policymakers capitalize on these fears, stoking them for political gain. The media also play a critical role in perpetuating a false narrative that communities are largely unsafe, amplifying public anxiety and reinforcing misguided approaches to crime.6

Public policy and scientific knowledge concerning deterrence have long been marching in different directions.7Michael Tonry

There is a tendency to support increasingly harsh punishments to deter others against crime, but evidence proves this impulse wrong. Although one stated rationale for lengthy sentences is to discourage criminal behavior through fear of punishment, research consistently shows that increasing the severity of sentences has minimal impact on crime reduction. Certainty of punishment, rather than its severity, is a more effective deterrent.8

Deterrence fails particularly for individuals who commit crimes in impulsive or emotionally charged situations, where rational decision-making is often in short supply.9

Significant progress has been made in restricting life sentences to people who were under age 18 at the time of their offense. A growing number of states now extend protections to older adolescents based on current research on brain development. This report provides the first state-level data on individuals whose offense occurred before age 25, highlighting the developmental parallels between emerging adults and those under 18.10 Emerging adults and youth share similar cognitive and emotional traits, such as ongoing brain development and impulsivity, which influence culpability.

Reoffending by persons who have been released from long-term or life sentences is rare. The Bureau of Justice Statistics shows that 66% of people released from prison are rearrested within three years.11 However, recidivism rates are very different for those released after long-term incarceration and for individuals who are middle-aged or older at the time of release. Numerous studies have found that individuals released after serving life sentences reoffend at significantly lower rates12

Most people who have served sufficient sentences can succeed on release but some will reoffend. Policymakers and the public must accept that some level of risk is unavoidable. Striking a balance between the goals of a crime-free society and respect for human rights is crucial. Investment in successful reentry will reap far greater outcomes than widespread lifetime imprisonment.

States and the federal government should implement a 20-year maximum on all prison terms, with exceptions only for rare circumstances. The funds saved by reducing excessive incarceration could be reallocated to disadvantaged communities that lack sufficient economic and public health support to combat crime, thereby improving social outcomes and community safety. The heavy investment in mass incarceration has exacerbated conditions in our poorest communities, making them more susceptible to crime. Strengthening these communities necessitates a robust reinvestment of resources used to sustain mass incarceration.13

Number of People Serving Life Sentences

The year 2024 marked The Sentencing Project’s sixth national census of people serving life sentences.14 In 2024, nearly 200,000 people were serving life sentences with parole (LWP), life without parole (LWOP), or prison sentences reaching 50 years or longer, referred to as virtual life sentences. This total—194,803—means that one of every 6 people in prison, or 16% of the total prison population, is serving a life sentence.

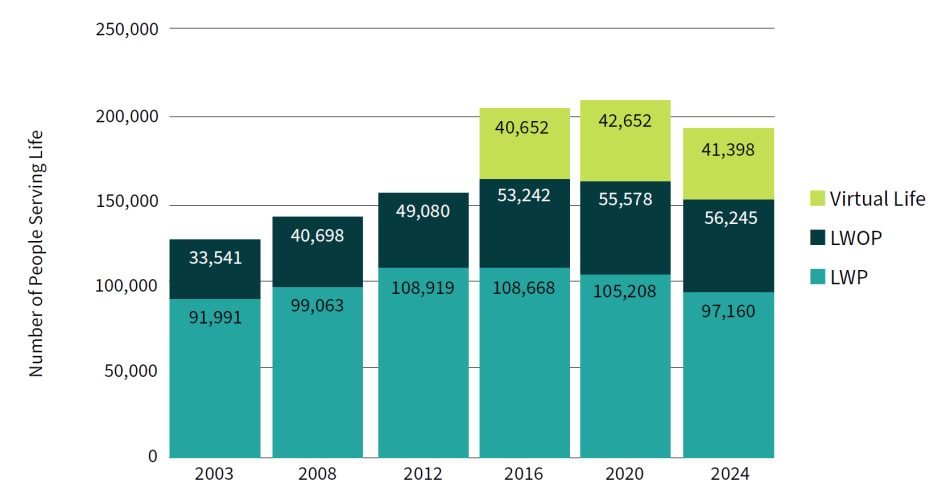

The comparison between The Sentencing Project’s initial count in 2003 and subsequent counts through 2024 shows that LWP sentences have declined by 11% since their peak in 2012, but remain 6% higher than in 2003.

Figure 1. Trends in Life Imprisonment, 2003-2024

Sources: The Sentencing Project has collected data directly from state departments of corrections and the Federal Bureau of Prisons on the number of people serving life sentences in 2003, 2008, 2012, 2016, 2020, and 2024. Note that The Sentencing Project’s count of people serving virtual life sentences began in 2016.

Conversely, there were more people serving LWOP in 2024 than ever, with 56,245 people serving this “death by incarceration” sentence—a 68% increase since 2003.

Though the year 2024 marked an all-time high for the proportion of people in prison who are serving life, it also reflected a drop of over 8,500 in the absolute number of people serving life since 2020. That these statistics trend in opposite directions came about partly because of a decline in the prison population overall. Between 2020 and 2024, state and federal prison populations decreased 13%, from 1.4 million people to 1.2 million people. As sentencing reforms have led to state prisons downsizing by as much as 46% between 2013 and 2022 without increases in crime,15 they have largely excluded reforms for persons convicted of violence, which includes the most common conviction for people sentenced to life. Because the life-sentenced population has decreased far less than the overall prison population, its share of the total population has grown. But mass incarceration will not end without scaling back excessive sentences for people with violent crime convictions.

Table 1 shows the distribution of life sentences across the United States. The states with the largest life-sentenced prison populations are California (37,022), Texas (18,358), and Florida (15,366). As a proportion of each state’s total prison population, the states with the largest rates of life imprisonment are California (39%), Utah (35%), Alabama (29%), and Massachusetts (29%).

| Jurisdiction | Life With Parole | Life Without Parole | Virtual Life | Total Life Population | Percent of Prison Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 3,684 | 1,485 | 781 | 5,950 | 29% |

| Alaska | 0 | 0 | 431 | 431 | 10% |

| Arizona | 1,218 | 634 | 16 | 1,868 | 5% |

| Arkansas | 684 | 552 | 893 | 2,129 | 11% |

| California | 30,102 | 5,111 | 1,809 | 37,022 | 39% |

| Colorado | 1,927 | 878 | 837 | 3,642 | 21% |

| Connecticut | 29 | 62 | 606 | 697 | 7% |

| Delaware | 71 | 371 | 220 | 662 | 16% |

| Florida | 3,138 | 10,915 | 1,313 | 15,366 | 18% |

| Georgia | 7,679 | 1,949 | 764 | 10,392 | 20% |

| Hawaii | 274 | 26 | 19 | 319 | 8% |

| Idaho | 553 | 129 | 46 | 728 | 7% |

| Illinois | 0 | 1,613 | 2,134 | 3,747 | 13% |

| Indiana | 56 | 139 | 3,794 | 3,989 | 17% |

| Iowa | 27 | 967 | 224 | 1,218 | 15% |

| Kansas | 1,286 | 42 | 182 | 1,510 | 17% |

| Kentucky | 709 | 153 | 466 | 1,328 | 7% |

| Louisiana | 246 | 3,900 | 1,400 | 5,546 | 20% |

| Maine | 0 | 65 | 59 | 124 | 7% |

| Maryland | 2,072 | 424 | 1,132 | 3,628 | 23% |

| Massachusetts | 727 | 1,052 | 34 | 1,813 | 29% |

| Michigan | 728 | 3,551 | 561 | 4,840 | 15% |

| Minnesota | 384 | 167 | 21 | 572 | 7% |

| Mississippi | 386 | 1,718 | 222 | 2,326 | 12% |

| Missouri | 1,635 | 1,103 | 584 | 3,322 | 14% |

| Montana | 53 | 50 | 439 | 542 | 19% |

| Nebraska | 101 | 268 | 686 | 1,055 | 18% |

| Nevada | 1,884 | 559 | 67 | 2,510 | 24% |

| New Hampshire | 238 | 78 | 33 | 349 | 18% |

| New Jersey | 832 | 102 | 525 | 1,459 | 11% |

| New Mexico | 762 | 5 | 21 | 788 | 14% |

| New York | 6,299 | 303 | 204 | 6,806 | 21% |

| North Carolina | 1,329 | 1,725 | 886 | 3,940 | 13% |

| North Dakota | 45 | 50 | 11 | 106 | 6% |

| Ohio | 7,130 | 801 | 1,008 | 8,939 | 20% |

| Oklahoma | 1,990 | 958 | 637 | 3,585 | 17% |

| Oregon | 713 | 234 | 4 | 951 | 8% |

| Pennsylvania | 239 | 5,059 | 2,981 | 8,279 | 21% |

| Rhode Island | 198 | 25 | 15 | 238 | 15% |

| South Carolina | 718 | 1,297 | 331 | 2,346 | 14% |

| South Dakota | 0 | 172 | 242 | 414 | 11% |

| Tennessee | 1,812 | 301 | 1,905 | 4,018 | 21% |

| Texas | 7,923 | 1,562 | 8,873 | 18,358 | 14% |

| Utah | 2,182 | 77 | 0 | 2,259 | 35% |

| Vermont | 170 | 14 | 28 | 212 | 11% |

| Virginia | 863 | 1,244 | 1,374 | 3,481 | 16% |

| Washington | 2,240 | 533 | 245 | 3,018 | 22% |

| West Virginia | 284 | 304 | 165 | 753 | 12% |

| Wisconsin | 822 | 381 | 466 | 1,669 | 8% |

| Wyoming | 151 | 53 | 156 | 360 | 16% |

| Federal | 567 | 3,084 | 1,548 | 5,199 | 3% |

| Total | 97,160 | 56,245 | 41,398 | 194,803 | 16% |

Notes: Alaska does not have LWP or LWOP sentences. Parole-eligible life sentences are also not permitted in Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Maine, Pennsylvania, and South Dakota; the federal system no longer issues parole-eligible sentences. Most persons identified as serving LWP sentences in Florida, Iowa, Louisiana, and Pennsylvania had their LWOP sentences commuted resulting from a state or U.S. Supreme Court ruling that LWOP is unconstitutional for juveniles. See Methodology for additional notes on data we received.

Recent Trends in Life Imprisonment, 2020-2024

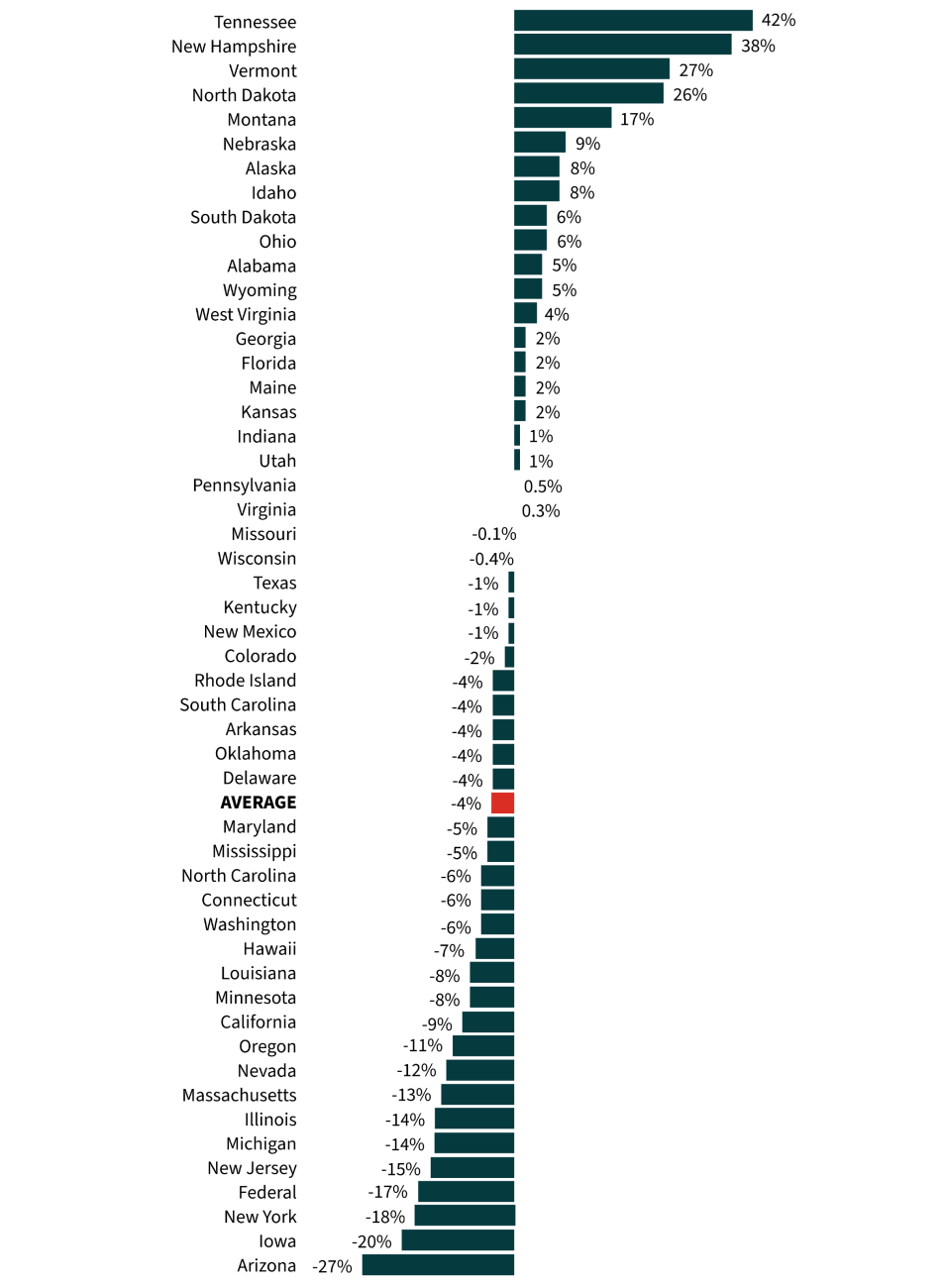

The United States makes up roughly 4% of the world population but holds an estimated 40% of the world’s life-sentenced population, including 83% of persons serving LWOP.16 In 2024, 21 states had more people serving a life sentence than they had in 2020. Between 2020 and 2024, across the country, the population serving life with parole (LWP) dropped by nearly 8%, the proportion of people sentenced to virtual life imprisonment remained approximately the same, and life without parole (LWOP) continued to climb, though at a slower rate than in earlier years.

Between 2020 and 2024, the overall prison population decreased by nearly 13%. However, 15 of the 40 states that reduced their prison population saw increases in the number of individuals serving life sentences.

Life With Parole, 2024

A total of 97,160 people were serving parole-eligible life sentences in 2024. This includes a total reported figure of 567 people in the federal system.17 All states except Alaska, Illinois, Maine, and South Dakota reported persons serving LWP, with the lowest number of persons serving LWP in Iowa (27) and Connecticut (29).

California accounts for nearly a third (31%) of the national population of individuals serving life with parole (LWP). States with the next highest proportions of people with LWP sentences are Georgia (8%), Texas (8%), Ohio (7%), and New York (7%), which collectively amount to an additional 30% of the national LWP population.

A somewhat different picture emerges when considering the proportion of individuals serving LWP in relation to each state’s prison population. Table 2 identifies the five states with the highest percentage of their prison populations serving LWP. In New York and California, for example, the proportion is high because of a substantial drop in the states’ overall prison populations. The state-level data reveal how heavily certain states rely on LWP as a prison sentence, relative to the size of their prison systems.

| State | LWP as Percentage of Prison Population |

|---|---|

| Utah | 34% |

| California | 32% |

| New York | 19% |

| Alabama | 18% |

| Nevada | 19% |

Life With Parole Changes, 2020-2024

Over two-thirds of states and the Federal Bureau of Prisons reported 8,048 fewer people serving life with parole in 2024 than in 2020. This 8% overall drop was driven by substantial declines in California (3,765 fewer people in 2024 compared to 2020), New York (1,404 fewer), and the federal system (458 fewer).

The decline in people serving life with parole since 2020 was likely due to a few co-occurring trends: fewer sentences imposed, more releases to parole, and deaths while awaiting parole. Almost 2,500 people in state and federal prisons died from Covid-19 between March 2020 and February 2021, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Eighty-three percent of these Covid-19 deaths occurred in persons 55 or older.18 We suspect that many of these deaths were among people serving life and long-term prison sentences.

Eleven states reported increases in the number of people serving LWP. These increases can be difficult to interpret. An increased LWP population may reflect resentencing or commutations from LWOP to LWP,19 or could reflect new life sentences added.

Figure 2. Percentage Change Among Life-Sentenced Population From 2020 to 2024

Note: Percentage changes can signify very different impacts depending on the size of the life-sentenced population in each state. In New Hampshire, for instance, the 39% increase represents an additional 97 people. Georgia, by comparison, added a total of 244 people, but the percentage increase is only 2%.

Life Without Parole, 2024

In 2024, there were 56,245 people serving LWOP within state systems and in the Federal Bureau of Prisons, led by Florida (10,915), and followed by California (5,111), Pennsylvania (5,059), Louisiana (3,900), and Michigan (3,551). The Federal Bureau of Prisons reported 3,084 people serving LWOP in 2024. As shown in Table 3, in Massachusetts,20 Louisiana, Pennsylvania, Florida, Iowa, and Michigan, between 10% and 17% of the prison populations were serving life without any chance of parole.

| State | LWOP as Percentage of Prison Population |

|---|---|

| Massachusetts | 17% |

| Louisiana | 14% |

| Pennsylvania | 13% |

| Florida | 13% |

| Iowa | 12% |

| Michigan | 11% |

Note: Massachusetts’s total prison population is disproportionately small in comparison to that of the other states.

A signature element of the “tough-on-crime” movement in the 1980s and 1990s that demanded harsher punishments in response to crime was the abolishment of parole. Following the federal government’s elimination of parole in 1987, nearly a dozen states did the same, including Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, and Washington. In several of these states, we see that the majority of the life-sentenced population is serving LWOP.21 Every state except Alaska allows LWOP, and more than half the states require this sentence upon conviction for some offenses, usually first-degree murder. In states including Louisiana and Pennsylvania, first- and second-degree murder convictions require LWOP.22

Life Without Parole, 2020-2024 Changes

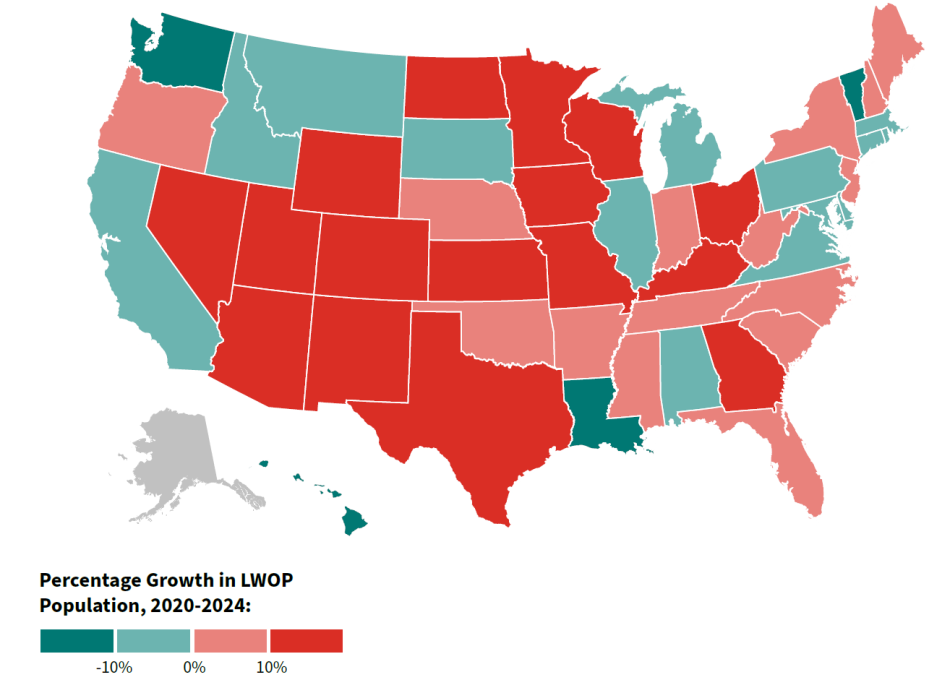

Since 2020, the population serving life without parole (LWOP) has grown by 1.2%, adding 667 individuals over the past four years. Figure 3 indicates the growth in the LWOP population from 2020 to 2024. In 2024, 30 states imprisoned more people sentenced to LWOP than they did in 2020. In 16 states, the population of people serving LWOP increased by more than 10% in just the last four years.

Following a series of U.S. Supreme Court rulings restricting the use of LWOP for youth, efforts to reduce or eliminate LWOP sentences for a broader cohort have spread. As a result of continued reforms, there are sizable decreases in the number of people serving LWOP over the past four years in some jurisdictions. In Louisiana, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and the federal system—each with several thousand individuals serving LWOP—there are far fewer people serving “death by incarceration” sentences than in the past. In Louisiana, for example, hundreds of individuals who were under 18 at the time of their offense were resentenced to life with the possibility of parole due to legal reforms. Additionally, before he left office, Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards commuted the LWOP sentences of more than 100 people.23 Sentencing reforms that introduced parole eligibility for lifers convicted of nonviolent offenses have also contributed to the decrease in this population. Alas, the LWOP population also decreases as people pass away while serving this sentence.

Figure 3. Growth of LWOP Population, 2020-2024

Note: Alaska does not have LWOP (or LWP) sentences.

Virtual Life, 2024

The Sentencing Project defines life sentences more broadly than just those officially labeled in statutes as life with parole or life without parole. For this research, we classify any sentence that results in the individual serving a significant portion or the remainder of their natural life in prison as a form of life imprisonment, even if it is not explicitly categorized as such by statute. These sentences functionally amount to life sentences due to their length and the limited opportunities for release.24 Virtual life sentences refer to term-of-years sentences that can amount to a maximum of 50 years or more before release.

Virtual life sentences—de facto life sentences often intended to keep individuals incarcerated for the rest of their lives—made up 21% of the total life-sentenced population in 2024, with states and the Federal Bureau of Prisons reporting 41,398 people serving virtual life sentences. This total is led by populations in Texas (8,873), Indiana (3,794), Pennsylvania (2,981), Illinois (2,134), and Tennessee (1,905). In Texas, nearly half of the state’s life-sentenced population was serving a virtual life sentence. Table 4 highlights the five states with the highest percentage of their prison population serving a virtual life sentence.

| State | Virtual Life as Percentage of Prison Population |

|---|---|

| Indiana | 16% |

| Montana | 15% |

| Nebraska | 12% |

| Tennessee | 10% |

| Alaska | 10% |

Virtual Life Changes, 2020-2024

From 2020 to 2024, the overall number of people serving virtual life sentences dropped by 1,254 individuals. While the federal government and many states collectively reduced the virtual life population, several states significantly increased the number of individuals serving sentences reaching 50 years or more, as shown in Table 5.

| State | Population Increase | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|

| Tennessee | 1,215 | 176% |

| Pennsylvania | 174 | 6% |

| Montana | 83 | 23% |

| Nebraska | 73 | 12% |

| Indiana | 70 | 2% |

Frederick Page

In 1989, at age 29, Frederick Page was sentenced to a virtual life sentence of 42 ½ to 102 years in Philadelphia, PA for seventeen misdemeanor burglaries — a sentence with the potential to exceed his life. Over three decades in prison, Page has worked hard to make amends for his past and is focused on a positive path forward. Among his accomplishments is a Bachelor’s Degree and a journeyman’s license in plumbing with a certificate in carpentry. In addition, Page is the co-founder of the Community Forgiveness & Restoration re-entry program.

Page’s case has been assigned for review by Philadelphia’s Conviction Integrity Unit — a unit which has expanded efforts at investigating bias and sentencing inequities in recent years. Hopeful about this new opportunity for sentencing review, Page continues to reckon with the challenges and inadequacies of the criminal legal system: “Rehabilitation is more than just a word, it is a force in action/motion — which has been one of the critical missing ingredients from the criminal justice system.”25

Page’s lengthy prison sentence is no longer doing the work of justice, and his situation is not unique. He is one of 2,981 Pennsylvanians serving a virtual life sentence in the state.

Characteristics of People Serving Life

Race and Ethnicity

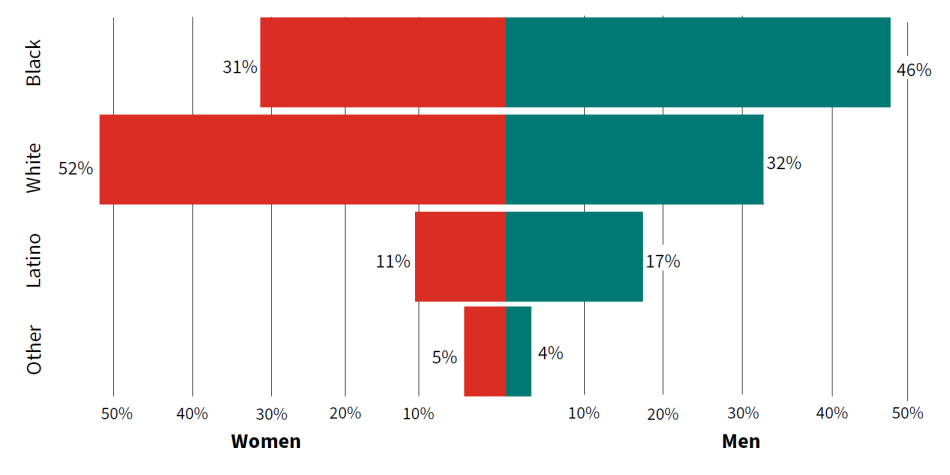

People of color, particularly Black Americans, experience disproportionately higher rates of arrest, conviction, and sentencing, due to the forces of both implicit and explicit bias.26 They also experience higher rates of both committing and being victims of homicide 27 Racial disparities are especially pronounced among people serving life sentences. More than two-thirds (67%) of all people serving life sentences are people of color; nearly 17% are Latino.28 Within the three types of life sentences— life without parole, life with parole, and virtual life sentences—the greatest racial imbalance is seen among individuals sentenced to LWOP, the harshest of the three. More than half (55%) of persons serving LWOP are Black.

Table 6 offers a closer look at the racial and ethnic composition of the life-sentenced population in each state. Across all 50 states, one in five Black individuals in prison is serving a life sentence. In seven states—Alabama, California, Colorado, Georgia, Massachusetts, Montana, and Utah—more than one in four Black people in prison is serving a life sentence.29 This trend reflects broader racial injustices contributing to differential patterns of criminal offending, and the fact that Black Americans are more likely to receive harsher sentences, even when controlling for the type of crime committed.30

| State | Life Pop. | % Black | % White | % Latino | % Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 5,950 | 66% | 33% | NA | 0% |

| Alaska | 431 | 12% | 46% | 2% | 40% |

| Arizona | 1,868 | 19% | 40% | 35% | 6% |

| Arkansas | 2,129 | 53% | 44% | 2% | 1% |

| California | 37,022 | 31% | 20% | 41% | 8% |

| Colorado | 3,642 | 24% | 44% | 26% | 6% |

| Connecticut | 697 | 54% | 29% | 17% | 0% |

| Delaware | 662 | 62% | 38% | NA | 0% |

| Florida | 15,366 | 53% | 35% | 12% | 1% |

| Georgia | 10,392 | 71% | 25% | 3% | 1% |

| Hawaii | 319 | 7% | 24% | 4% | 61% |

| Idaho | 728 | 3% | 78% | 13% | 6% |

| Illinois | 3,747 | 66% | 24% | 10% | 1% |

| Indiana | 3,989 | 48% | 46% | 4% | 2% |

| Iowa | 1,218 | 27% | 62% | 7% | 3% |

| Kansas | 1,510 | 37% | 49% | 10% | 3% |

| Kentucky | 1,328 | 29% | 68% | 2% | 1% |

| Louisiana | 5,546 | 72% | 27% | NA | 0% |

| Maine | 124 | 10% | 81% | 0% | 10% |

| Maryland | 3,628 | 76% | 19% | 3% | 2% |

| Massachusetts | 1,813 | 34% | 41% | 22% | 4% |

| Michigan | 4,840 | 66% | 30% | 2% | 3% |

| Minnesota | 572 | 40% | 45% | 6% | 10% |

| Mississippi | 2,326 | 72% | 27% | 1% | 0% |

| Missouri | 3,322 | 48% | 48% | 2% | 1% |

| Montana | 542 | 5% | 83% | 1% | 11% |

| Nebraska | 1,055 | 31% | 49% | 15% | 6% |

| Nevada | 2,510 | 25% | 45% | 26% | 5% |

| New Hampshire | 349 | 7% | 83% | 6% | 4% |

| New Jersey | 1,459 | 60% | 17% | 13% | 10% |

| New Mexico | 788 | 9% | 31% | 52% | 8% |

| New York | 6,806 | 55% | 18% | 24% | 3% |

| North Carolina | 3,940 | 59% | 34% | 3% | 3% |

| North Dakota | 106 | 14% | 66% | 7% | 13% |

| Ohio | 8,939 | 51% | 45% | 2% | 1% |

| Oklahoma | 3,585 | 35% | 49% | 6% | 9% |

| Oregon | 951 | 11% | 71% | 13% | 5% |

| Pennsylvania | 8,279 | 61% | 27% | 9% | 1% |

| Rhode Island | 238 | 39% | 36% | 24% | 5% |

| South Carolina | 2,346 | 67% | 31% | 1% | 1% |

| South Dakota | 414 | 9% | 64% | 4% | 22% |

| Tennessee | 4,018 | 56% | 41% | 2% | 0% |

| Texas | 18,358 | 39% | 32% | 27% | 1% |

| Utah | 2,259 | 7% | 57% | 21% | 14% |

| Vermont | 212 | 6% | 90% | 0% | 3% |

| Virginia | 3,481 | 61% | 38% | NA | 1% |

| Washington | 3,018 | 15% | 60% | 15% | 10% |

| West Virginia | 753 | 16% | 84% | 0% | 1% |

| Wisconsin | 1,669 | 47% | 39% | 10% | 4% |

| Wyoming | 360 | 6% | 77% | 8% | 8% |

| Total | 194,803 | 45% | 32% | 16% | 3% |

Notes: The Federal Bureau of Prisons did not provide any demographic information for people serving life. Due to rounding, percentages may not add up to 100 in every case.

NA=not available; race / ethnicity was not provided.

Sex

The overwhelming majority of people sentenced to life in prison are men. Table 7 provides a state-by-state breakdown of women serving a life sentence. The 6,829 women who were serving life sentences in 2024 represent less than 4% of the overall life-sentenced population.

Though that percentage seems small, it amounts to one in every 11 women in prison serving a life sentence. In eight states—Alabama, Alaska, California, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Hampshire, Vermont—more than one in six women in prison are serving a life sentence.31

| State | LWP | LWOP | Virtual | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 133 | 63 | 39 | 235 |

| Alaska | 0 | 0 | 18 | 18 |

| Arizona | 50 | 40 | 0 | 90 |

| Arkansas | 37 | 25 | 25 | 87 |

| California | 869 | 178 | 7 | 1,054 |

| Colorado | 20 | 31 | 23 | 74 |

| Connecticut | 0 | 2 | 16 | 18 |

| Delaware | 0 | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| Florida | 82 | 243 | 26 | 351 |

| Georgia | 385 | 67 | 35 | 487 |

| Hawaii | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Idaho | 30 | 6 | 1 | 37 |

| Illinois | 0 | 41 | 56 | 97 |

| Indiana | 2 | 5 | 140 | 147 |

| Iowa | 1 | 38 | 13 | 52 |

| Kansas | 65 | 2 | 1 | 68 |

| Kentucky | 41 | 11 | 9 | 61 |

| Louisiana | 23 | 111 | 21 | 155 |

| Maine | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Maryland | 56 | 14 | 24 | 94 |

| Massachusetts | 26 | 27 | 0 | 53 |

| Michigan | 22 | 145 | 6 | 173 |

| Minnesota | 12 | 8 | 0 | 20 |

| Mississippi | 9 | 103 | 6 | 118 |

| Missouri | 65 | 47 | 10 | 122 |

| Montana | 5 | 1 | 16 | 22 |

| Nebraska | 2 | 14 | 27 | 43 |

| Nevada | 99 | 40 | 7 | 146 |

| New Hampshire | 20 | 4 | 2 | 26 |

| New Jersey | 15 | 3 | 12 | 30 |

| New Mexico | 29 | 0 | 1 | 30 |

| New York | 158 | 10 | 2 | 170 |

| North Carolina | 25 | 90 | 11 | 126 |

| North Dakota | 4 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Ohio | 361 | 34 | 12 | 407 |

| Oklahoma | 146 | 63 | 16 | 225 |

| Oregon | 52 | 11 | 0 | 63 |

| Pennsylvania | 7 | 189 | 79 | 275 |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| South Carolina | 26 | 46 | 7 | 79 |

| South Dakota | 0 | 3 | 10 | 13 |

| Tennessee | 127 | 14 | 129 | 270 |

| Texas | 301 | 83 | 326 | 710 |

| Utah | 64 | 2 | 0 | 66 |

| Vermont | 6 | 3 | 2 | 11 |

| Virginia | 17 | 25 | 261 | 303 |

| Washington | 25 | 18 | 6 | 49 |

| West Virginia | 23 | 29 | 8 | 60 |

| Wisconsin | 37 | 9 | 4 | 50 |

| Wyoming | 7 | 0 | 8 | 15 |

| Total | 3,494 | 1,909 | 1,426 | 6,829 |

Note: The Federal Bureau of Prisons did not provide any demographic information for people serving life.

Compared to the racial and ethnic demographics for men, a larger share of women serving life sentences are white, as shown in Figure 4. This tracks with prison populations generally, which consistently show that white women are a significant and growing share of the female prison population.32

Figure 4. Population Serving Life by Sex and Race, 2024

Note: This figure excludes data from Montana, Virginia, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons. These jurisdictions did not provide a race/ethnicity breakdown of women and men serving life sentences.

Elderly Status

Aging is a universal experience that carries additional significant challenges for those who are incarcerated. Aging occurs more rapidly in prison, with health and longevity negatively impacted. Many incarcerated individuals entered prison with poor health, and the conditions of imprisonment worsen chronic and age-related ailments. Studies show that compared to nonincarcerated individuals, incarcerated people experience worse health outcomes, including higher rates of chronic illness, infectious diseases, and psychological disorders.33

In 2024, a reported 69,142 people aged 55 and older were serving life sentences, making up more than a third (35%) of the life-sentenced population (see Figure 5 and Table 8). In four states—Connecticut, Hawaii, Michigan, New Jersey—half or more of the life-sentenced populations are elderly.

There has also been a 13% increase since 2020 in people 55 and older serving life. We can attribute this to a share of life-sentenced people aging into the elderly category over the four-year period, as well as a slight increase in new life sentences added. Regardless of cause, this growth highlights the inadequate policy and administrative efforts to release elderly individuals who have served lengthy sentences, and who pose minimal risk of reoffending. Particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic (which occurred between the 2020 and 2024 periods of data collection), when this population faced the highest risk of illness and death, officials did far too little to protect this vulnerable population.34

Figure 5. Elderly Status of Life-Sentenced People in Prison, 2024

Note: This figure excludes data from Iowa, Virginia, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons. These jurisdictions did not provide data on the number of life-sentenced individuals over the age of 55.

| State | LWP | LWOP | Virtual | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 1,697 | 697 | 274 | 2,668 |

| Alaska | 0 | 0 | 163 | 163 |

| Arizona | 511 | 21 | 10 | 542 |

| Arkansas | 391 | 212 | 216 | 819 |

| California | 10,814 | 1,642 | 636 | 13,092 |

| Colorado | 765 | 316 | 261 | 1,342 |

| Connecticut | 29 | 21 | 313 | 363 |

| Delaware | 67 | 164 | 76 | 307 |

| Florida | 2,705 | 3,405 | 679 | 6,789 |

| Georgia | 2,369 | 460 | 224 | 3,053 |

| Hawaii | 144 | 14 | 10 | 168 |

| Idaho | 220 | 69 | 9 | 298 |

| Illinois | 0 | 898 | 551 | 1,449 |

| Indiana | 56 | 46 | 1,093 | 1,195 |

| Kansas | 342 | 9 | 75 | 426 |

| Kentucky | 345 | 40 | 200 | 585 |

| Louisiana | 97 | 1,773 | 399 | 2,269 |

| Maine | 0 | 32 | 28 | 60 |

| Maryland | 907 | 150 | 257 | 1,314 |

| Massachusetts | 288 | 453 | 23 | 764 |

| Michigan | 500 | 2,027 | 196 | 2,723 |

| Minnesota | 157 | 34 | 4 | 195 |

| Mississippi | 249 | 478 | 37 | 764 |

| Missouri | 605 | 441 | 249 | 1,295 |

| Montana | 17 | 24 | 164 | 205 |

| Nebraska | 28 | 104 | 146 | 278 |

| Nevada | 603 | 263 | 6 | 872 |

| New Hampshire | 105 | 46 | 12 | 163 |

| New Jersey | 493 | 41 | 206 | 740 |

| New Mexico | 274 | 1 | 1 | 276 |

| New York | 2,143 | 85 | 122 | 2,350 |

| North Carolina | 997 | 440 | 396 | 1,833 |

| North Dakota | 15 | 14 | 4 | 33 |

| Ohio | 2,276 | 195 | 694 | 3,165 |

| Oklahoma | 766 | 317 | 298 | 1,381 |

| Oregon | 276 | 106 | 4 | 386 |

| Pennsylvania | 25 | 2,149 | 876 | 3,050 |

| Rhode Island | 59 | 14 | 7 | 80 |

| South Carolina | 549 | 432 | 88 | 1,069 |

| South Dakota | 0 | 103 | 66 | 169 |

| Tennessee | 536 | 95 | 486 | 1,117 |

| Texas | 3,209 | 256 | 3,224 | 6,689 |

| Utah | 558 | 23 | 0 | 581 |

| Vermont | 69 | 6 | 12 | 87 |

| Washington | 604 | 298 | 76 | 978 |

| West Virginia | 70 | 140 | 42 | 252 |

| Wisconsin | 294 | 113 | 182 | 589 |

| Wyoming | 82 | 19 | 55 | 156 |

| Total | 37,306 | 16,686 | 13,150 | 69,142 |

Note: Iowa, Virginia, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons did not provide data on life-sentenced individuals over the age of 55.

Crime of Conviction

Homicide and Other Crimes of Violence

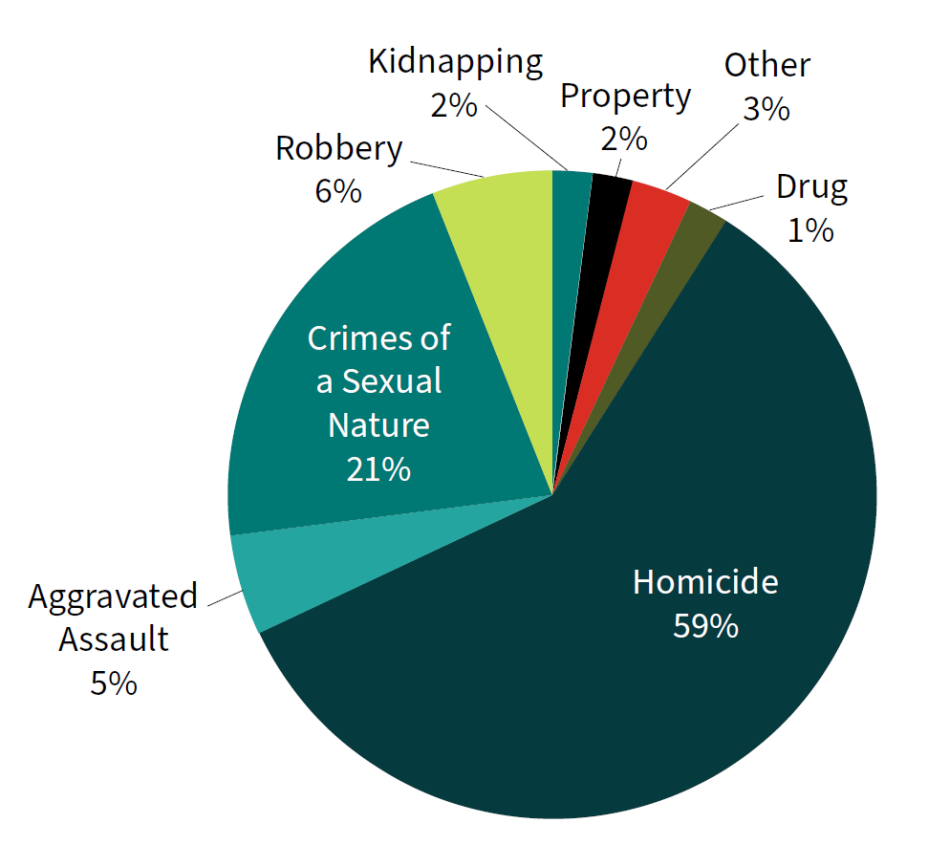

Most individuals serving life sentences have been convicted of a violent crime. Homicide convictions—primarily for first-degree murder—accounted for 59% of the life-sentenced population in 2024. In most states, LWOP is the mandatory sentence for first-degree murder convictions, and in states with capital punishment, LWOP is typically required if a death sentence is not imposed.

In states such as Pennsylvania and Michigan, substantial proportions of people serving life sentences for murder were convicted of “felony murder.” This category of offense applies in cases in which someone was killed during the commission of a felony; this charge can apply to people who neither intended to kill nor anticipated a death, and can even apply to persons who did not participate in the killing.35

In 2024, 25,395 people—a total of 14% of people serving life—had been convicted of aggravated assault, robbery, or kidnapping (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Distribution of Crime of Conviction Among People Serving Life Sentences, 2024

Note: This figure excludes data from Virginia and the Federal Bureau of Prisons. These jurisdictions did not provide full crime of conviction data on life-sentenced populations. Category totals do not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Crimes of a Sexual Nature

One in five people serving life sentences in 2024 had been convicted of a crime of a sexual nature (CSN). Recidivism rates for CSN have declined by 45% since the 1970s, and sexual assault victimization has decreased by roughly 65% across the last three decades.36 Still, since the 1990s, responses to CSN have become increasingly punitive, with individuals receiving longer sentences and, on average, serving a greater percentage of their sentences relative to persons incarcerated for other violent crimes, even murder.37

Nonviolent Offenses

Individuals serving life sentences as a result of being convicted of nonviolent crimes comprise 3% of all people serving life sentences in 2024, or 6,199 people. There are 1,945 people serving life sentences for drug-related offenses. Of the 49 states that provided offense data, 11 reported not imprisoning anyone with a life sentence for this offense.40 Within the federal system, 939 people are serving a life sentence for a drug-related crime. Over 4,000 individuals are serving a life sentence for property crimes—another nonviolent offense. Eleven states reported not imprisoning anyone with a life sentence for this offense—it is worth noting these are not the exact same states which report zero life-sentences for drug offenses.41

The high incarceration rates in Louisiana and Mississippi can be partly attributed to their “habitual offender” laws. Under these laws, someone can be sentenced to life or a virtual life sentence upon a second or third conviction, regardless of how far in the past the previous crimes occurred. Habitual offender laws are a tool used by prosecutors to ensure a life sentence.

Investigative reporting by The Appeal of the laws in Louisiana and Mississippi found that close to 2,000 people were serving life and long-term sentences in these two states because of these sentencing “enhancements.”42

Youth and Emerging Adulthood

In 2024, a total of 68,429 people—more than one-third of all life-sentenced individuals—were under the age of 25 when they committed their crime. This report provides the first-ever state-by-state totals of persons serving life sentences for crimes that occurred before age 25 (see Table 10).43 Given emerging neuroscience on brain development and culpability, The Sentencing Project highlights this population as more states reevaluate the appropriate age for holding individuals fully accountable for crimes. States must confront this data, particularly where young individuals—whose cognitive and emotional development are still ongoing—are disproportionately serving life sentences. This information is crucial for evidence-based policy reform aimed at balancing justice with evolving understandings of human development.

Judicial and legislative recognition of emerging adults, typically defined as individuals from 18 up to 25 years of age, has resulted in significant reforms in states addressing the treatment of emerging adults within the justice system.44 These reforms often center on recognizing the developmental differences between adults and youth, especially given the advancements in adolescent neuroscience. For instance, Washington, DC allows for resentencing opportunities for individuals who were under age 25 when they committed their offense.45 Judges in Washington, DC are required to consider factors such as young age, childhood abuse, and rehabilitation efforts. Similarly, Vermont and Illinois have implemented reforms that either extend juvenile court jurisdiction or prohibit life without parole (LWOP) sentences for those under 21. California allows accelerated parole review for life-sentenced individuals younger than 26 at the time of their crime.46

An increasing number of judicial rulings support late adolescence, marked by impulsivity and risk-taking, as a critical developmental stage that warrants more moderate sentencing considerations. Courts in Massachusetts, Michigan, and Washington have recognized that 18-year-olds are still not fully developed and thereby ruled mandatory LWOP for these teens unconstitutional under their state constitutions.47

The data presented here cover individuals serving life with parole, life without parole, and virtual life sentences for crimes committed before their twenty-fifth birthday (see Figure 7). These figures help to describe the broader spectrum of individuals who could benefit from reforms that align with recent advances in adolescent and emerging adult neuroscience. As more research indicates the reality of reduced culpability and the considerable potential for change among young adults, there is growing pressure to extend legal protections and reconsider extreme sentencing for this population.

Figure 7. People Sentenced as Youth and Emerging Adults, by Type of Life Sentence, 2024

Note: This figure excludes data from Missouri and the Federal Bureau of Prisons. These jurisdictions did not provide data on the age at sentencing for life-sentenced individuals.

Race and Young Age

Black people disproportionately represent those serving life sentences, and this racial disparity is even more pronounced among youth and emerging adults (see Figure 8). While Black individuals comprise 37% of adults sentenced to life with the possibility of parole (LWP) in 2024, they account for 48% of those sentenced to LWP who were under 25 at the time of their crime. Similarly, Black Americans aged 25 and older make up 50% of those serving life without the possibility of parole (LWOP), but that figure rises to 62% for those who were younger than 25 at the time of their crime.

As The Sentencing Project has highlighted in its previous analyses,48 the intersection of being young and Black leads to disproportionately higher rates of life sentences, suggesting that age exacerbates racial disparities in sentencing.

Figure 8. Racial and Ethnic Composition of Those Sentenced to Life as Youth and Emerging Adults Compared to Individuals 25 and Older, 2024

Table 11 highlights states where the share of Black individuals is 70% or greater within the population of individuals whose offense occurred prior to their 25th birthday. Although The Sentencing Project’s data alone cannot definitively prove causality, there is strong evidence that racism significantly affects the experiences of Black individuals in the criminal legal system, from initial system contact, to sentencing, and beyond. Research shows that Black children as young as age 10 are often perceived as older than they are, which affects how they are treated compared to white or Latino youth.49 Black children are less likely to be given the benefit of the doubt and are seen as more culpable for similar actions than their white and Latino peers. Such biased perceptions contribute to disparities in arrests, convictions, and sentencing outcomes. By the age of 23, 30% of Black males in America have been arrested, compared to 22% of non-Black males.50 It is possible that these factors contribute to the racial disparities we observe among those sentenced to LWOP as well.

Crime of Conviction Among Youth and Emerging Adults

Like the broader population of life-sentenced individuals, most people sentenced to life for crimes committed before age 25 were convicted of violent offenses, particularly homicide. However, when categorizing convictions according to age group, homicide is disproportionately common among those under 25, and life sentences among adults reflect a wider range of crimes: 74% of life sentences for emerging adults and youth (under 25) were for homicide, yet for adults (age 25 and older), 49% of life sentences were for homicide, based on 2024 data.

Why Life Sentences Fail

Historically, sentences of life imprisonment were reserved for the most severe crimes, with actual time served often ranging from 10 to 12 years.51 The justice system employed a balance of incentives and penalties, encouraging rehabilitation through mechanisms like early release and good behavior credits. However, in the past 40 years, this approach has shifted dramatically. Lawmakers have expanded the use of life sentences, applying them to a wider range of offenses, and increased the mandatory time people must serve before becoming eligible for parole.52 Opportunities for early release based on good behavior have diminished, and wait times for parole review have lengthened substantially. Today, the focus of life imprisonment has shifted from a balanced model of punishment and rehabilitation to one primarily centered on punishment, with little consideration for reform or second chances.

Extensive research has demonstrated that life sentences fail to achieve the primary objectives of imprisonment, which include deterrence, incapacitation, retribution, and rehabilitation.

The purported broad deterrent value of lengthening prison sentences is not supported by the evidence.53 People do not engage in the rational cost-benefit analysis that deterrence theory requires before they engage in crime. Many violent crimes are impulsive, emotionally driven, and committed without awareness of the gravity of the legal consequences. Yet claims of the benefits of “teaching people a lesson,” popularized as “tough on crime”, have supported harmful policies like three strike laws, mandatory minimum sentences, and habitual offender laws.54

Incapacitation as a goal of life sentences also fails. Most people age out of criminal conduct within a decade or so, and are usually “aged out” by their 30s.55 Imprisoning people for years or even decades beyond the point of dangerousness does not prevent crime.

The retributive principle of “an eye for an eye” often serves as the rationale for supporting life and long prison sentences, but upon closer examination, this logic falters. Francis Cullen, distinguished research professor emeritus at the University of Cincinnati’s School of Criminal Justice, argues that such punishments frequently become grossly disproportionate to the crimes committed given the wide variance in surrounding circumstances and culpability. These factors mean that the punishment rendered by life sentences far exceeds the balance intended by retributive justice. Additionally, these sentences are deeply affected by racial bias, further distorting any sense of fairness. Rather than ensuring justice, life sentences often impose far more punishment than is warranted by the offense, resulting in a system where the idea of proportionality is lost.56

Rehabilitation has often been unfairly stigmatized, but when implemented effectively, it produces meaningful results.57 Unfortunately, many life-sentenced individuals and people serving long-term sentences are excluded from rehabilitative programs. Because persons with shorter sentences receive priority access to rehabilitation opportunities, life-sentenced individuals can be left out completely or subjected to extremely long program waitlists.

Despite these barriers, peer-driven initiatives have emerged organically within prisons across states such as California, Louisiana, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. Lifer groups in these states have created supportive peer-to-peer rehabilitation communities that help imprisoned people work through their challenges, find friendship and acceptance, and contribute to personal transformation. Many released lifers credit these groups for their successful reintegration into society, underscoring the importance of community-driven recovery and rehabilitation efforts for those serving long sentences.58

By expanding access to these programs, particularly for people with long-term imprisonment, prisons can better fulfill the promise of rehabilitation.

| State | Percentage of Life-Sentenced Population Convicted of a Crime of a Sexual Nature |

|---|---|

| Washington | 72% |

| Utah | 58% |

| Colorado | 48% |

| Vermont | 46% |

| Idaho | 39% |

| State | LWP | LWOP | Virtual | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 1,109 | 404 | 255 | 1,768 |

| Alaska | 145 | 145 | ||

| Arizona | 513 | 211 | 16 | 740 |

| Arkansas | 239 | 272 | 238 | 749 |

| California | 11,119 | 2,380 | 540 | 14,489 |

| Colorado | 455 | 347 | 254 | 1,056 |

| Connecticut | 18 | 29 | 289 | 336 |

| Delaware | 30 | 130 | 62 | 222 |

| Florida | 1,431 | 3,854 | 484 | 5,769 |

| Georgia | 3,622 | 572 | 203 | 4,397 |

| Hawaii | 72 | 10 | 4 | 86 |

| Idaho | 116 | 22 | 11 | 149 |

| Illinois | 0 | 551 | 985 | 1,536 |

| Indiana | 19 | 49 | 1,092 | 1,160 |

| Iowa | 27 | 373 | 54 | 454 |

| Kansas | 477 | 10 | 42 | 529 |

| Kentucky | 223 | 29 | 141 | 393 |

| Louisiana | 178 | 1,647 | 540 | 2,365 |

| Maine | 0 | 15 | 19 | 34 |

| Maryland | 1,003 | 159 | 279 | 1,441 |

| Massachusetts | 360 | 471 | 8 | 839 |

| Michigan | 267 | 1,750 | 258 | 2,275 |

| Minnesota | 191 | 57 | 4 | 252 |

| Mississippi | 240 | 628 | 88 | 956 |

| Montana | 12 | 6 | 81 | 99 |

| Nebraska | 36 | 97 | 182 | 315 |

| Nevada | 659 | 110 | 6 | 775 |

| New Hampshire | 92 | 20 | 14 | 126 |

| New Jersey | 294 | 29 | 203 | 526 |

| New Mexico | 291 | 1 | 6 | 298 |

| New York | 2,204 | 97 | 48 | 2,349 |

| North Carolina | 681 | 679 | 285 | 1,645 |

| North Dakota | 13 | 5 | 0 | 18 |

| Ohio | 2,614 | 185 | 218 | 3,017 |

| Oklahoma | 615 | 251 | 58 | 924 |

| Oregon | 251 | 74 | 0 | 325 |

| Pennsylvania | 221 | 2,323 | 926 | 3,470 |

| Rhode Island | 66 | 7 | 6 | 79 |

| South Carolina | 388 | 398 | 154 | 940 |

| South Dakota | 0 | 54 | 68 | 122 |

| Tennessee | 921 | 112 | 748 | 1,781 |

| Texas | 3,092 | 514 | 2,759 | 6,365 |

| Utah | 559 | 26 | 0 | 585 |

| Vermont | 67 | 5 | 11 | 83 |

| Virginia | 211 | 304 | 335 | 850 |

| Washington | 591 | 108 | 90 | 789 |

| West Virginia | 5 | 2 | 2 | 9 |

| Wisconsin | 448 | 92 | 165 | 705 |

| Wyoming | 55 | 11 | 28 | 94 |

| Total | 36,095 | 19,930 | 12,404 | 68,429 |

Next Steps

Reforms such as abolishing LWOP, capping sentences at 20 years, taking a second look at lengthy sentences that have already been imposed, and broadening juvenile sentencing restrictions to include emerging adults are essential for an effective and humane punishment system. Parole boards and sentence review processes can be strengthened by improving transparency and due process for parole candidates. Sentences that have the same effect as statutorily defined life sentences should be marked for reforms as well. We offer specific guidance on each of these below.

Abolish LWOP. LWOP condemns individuals to die in prison without considering their capacity for change over time. Research shows that people—especially youth and emerging adults—possess significant potential for growth and rehabilitation, but LWOP sentences are indifferent to any such prospects. Furthermore, the racial disparities in LWOP sentencing disproportionately affect Black and Brown communities, exacerbating systemic racial injustice in the criminal legal system.

Cap imprisonment at 20 years, with rare exceptions, and for people under 25 years of age, limit maximum sentences to 15 years at most. This aligns with findings that long-term imprisonment does little to improve community safety. Studies indicate that recidivism rates drop significantly as individuals age, meaning that the deterrent effect of long sentences diminishes over time. For younger individuals, a sentence cap of 15 years acknowledges the developmental science showing that emerging adults (ages 18-25) are more capable of rehabilitation than older individuals are, and therefore warrant shorter sentences that allow for second chances. States should institute an automatic sentence review process within 10 years of imprisonment at most, with a rebuttable presumption of resentencing.

Expand current sentencing restrictions in light of the scientific evidence of similarities between youth and emerging adults. The growing consensus is that people under 25 are still undergoing significant cognitive development, so that their decision-making and impulse control can be negatively affected. The Sentencing Project advocates for reforms in this sphere because treating emerging adults as fully mature older adults fails to account for their diminished culpability. Expanding juvenile sentencing protections to cover emerging adults would allow for more developmentally appropriate responses to their crimes and would emphasize rehabilitation over punishment.

Strengthen parole boards and accelerate release. Parole boards can better respond to public safety concerns by focusing on rehabilitation of parole candidates while they are imprisoned and assessing their current risk, rather than concentrating on just the crime they committed. Establishing clear guidelines and providing detailed explanations for denials would improve board accountability and consistency. At review hearings, parole decisions should give added weight in favor of parole to advanced age. Advanced-age considerations should begin at age 50, in light of the accelerating aging process that accompanies imprisonment. Boards should also integrate the latest research on criminal behavior and human development to inform their decisions. And, while victim impact is important, it should be weighed alongside broader considerations of rehabilitation. Parole boards should take responsibility for enhancing post-release support by partnering with reentry programs to reduce recidivism and aid reintegration. Addressing racial disparities through bias training and increasing diversity within parole boards may lead to more equitable outcomes, focusing on fairness and long-term rehabilitation rather than punitive measures.

End stacked sentences that are longer than 20 years cumulatively. Stacked sentences, which consist of independent sentences levied for multiple charges that are to be applied consecutively instead of concurrently, also contribute to lengthy imprisonment. Stacked sentences often lead to punishments that far exceed the severity of the offenses, particularly in cases involving youth and emerging adults who may have engaged in impulsive or reckless behavior as a result of their still-developing brains. Reforms here would promote proportionality in sentencing, ensure that punishments are fair and just, and reduce reliance on extreme sentences.

Michael Montalvo

Michael Montalvo, a Vietnam War veteran, was convicted of a non-violent federal drug trafficking offense and sentenced to life without parole nearly four decades ago. He is serving a sentence far longer than he would receive today and far longer than the 15-year plea deal that he was offered before trial. Although two wardens have recommended granting Montalvo compassionate release, he is categorically ineligible for compassionate release as someone serving an “old law” sentence—having been convicted of an offense that occurred prior to the effective date of the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, November 1, 1987. His only path home is through presidential clemency.

Montalvo’s record while incarcerated has been exemplary. He has completed over 120 Bureau of Prisons programs, has earned four university degrees, has tutored numerous individuals over thirty years, earned excellent work reports, and is a devoted advocate for all “old law” individuals. The Sentencing Project continues to drive advocacy efforts fighting for legislative reforms that would make “old law” elderly individuals eligible for compassionate release.60

Conclusion

The Sentencing Project’s sixth national census of life sentences reveals that one in six individuals in U.S. prisons was serving a life sentence in 2024. Given the reduced overall prison population, this is a record high proportion of life sentences. A surge in life without parole (LWOP) sentences means that 56,245 people were serving LWOP in 2024, marking a 68% increase since 2003. Racial disparities remain stark, as nearly half of people serving life sentences in 2024 were Black, with younger Black individuals disproportionately affected. Additionally, 35% of those serving life were aged 55 or older, and nearly one-third of people sentenced to life for offenses that were committed before they were 25 will have no chance of parole. Moreover, one in 11 women in prison was serving a life sentence, underscoring the widespread use of this severe punishment across diverse demographics.

Life imprisonment in the United States has proven to be a deeply flawed crime control method that disproportionately impacts communities of color, particularly Black Americans. Unlike other economically advanced nations where life sentences are rare and more narrowly applied, the U.S. has embraced life sentences over the past four decades at alarming rates, often without apparent regard for fairness or justice.

States and the federal government should limit prison terms to a maximum of 20 years, except in rare cases, and redirect resources toward improving economically disadvantaged communities. Such reinvestment, rather than perpetuating mass incarceration, will be a more effective way to combat crime and promote long-term community safety.

Kimonti Carter

In 1998, the State of Washington sentenced Kimonti Carter to a mandatory life sentence without the possibility of parole for an offense he committed in 1997 at the age of 18. In 2022, after 25 years of incarceration, he gained release with time-served under the authority of the Washington Supreme Court’s 2021 decision in Monschke, which held that mandatory LWOP sentences for individuals under 21 violated the state’s constitution. The Pierce County Prosecutor appealed his release on the basis that any sentence less than life without parole was not authorized by the legislature. In 2024, the State Supreme Court rejected this position and the request to reinstate Carter’s sentence, noting the heightened capacity for change among those under 21 years old. Since his release, Carter has become a prominent advocate for justice reform. He is featured in the award-winning documentary Since I Been Down, works as a Community Outreach Specialist at the Washington State Office of Public Defense, serves as Community Mobilization Director for Participatory Justice, and is President of The Black Prisoners Caucus. Committed to fighting mass incarceration, Kimonti continues to inspire and organize communities for change.61

Methodology

Data Collection and Analysis

The data collection process for this research report follows the same method The Sentencing Project used in previous years when gathering information about people serving life sentences.

Every state was initially contacted by email in January 2024 to request that they complete our survey instrument (see Appendix). By September 1, 2024, all states and the federal government responded with their completed survey instrument or provided the necessary data for us to complete it.

Forty-six states provided responses to all sections of the survey. Six additional states (Iowa, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, and Virginia) and the federal government provided data for at least some portion of the survey. When possible, we estimated 2024 numbers for these jurisdictions based on data they supplied in previous years.

As in past years, when we reached out to states for data, we invited them to review their previous submission to check for accuracy and compare it to their current submission. States were able to submit corrections to us until the time that they submitted their current numbers.

Definitions

We think it useful to describe our decision-making process with respect to defining certain terms, beginning with our characterization of elderly lifers as 55 or older. There is no universally agreed-upon age at which imprisoned individuals are deemed elderly; however, people who are incarcerated begin to develop health concerns at an earlier age than those who are not in prison. While there is not yet consensus in the literature about the age at which an incarcerated individual should be classified as elderly, we frequently see 50 or 55 used as the cutoff. In an effort to be conservative, we asked states to report certain data for incarcerated people aged 55 and older.

Virtual life imprisonment is another term without a set definition. Though the mention of “virtual life” or “de facto” life sentences has become more frequent in scholarly and policy discussions of life imprisonment, the exact number of years that equate to “virtual life” is not yet settled. Montclair University legal scholar, Jessica Henry, noted the difficulty in setting a term of years to define virtual life because the age of an individual at the time of prison admission is critical to that calculation.62 The courts have diverged on where to draw the line.

Again, we conservatively selected 50 years as the threshold for a virtual life sentence based on the following rationale: The life expectancy of a 33-year-old male (the typical age and sex for someone entering prison with a homicide conviction) serving a long-term or life sentence would be about 40 additional years. This suggests that to survive a lengthy sentence, one must be released before the age of 73. Add to this the increased probability of a premature death for those who are incarcerated and a maximum sentence of 50 years or more as equivalent to “virtual life” is reasonable.

Departments of corrections provided data on incarcerated people who could be released before serving their maximum sentence through “good-time” credits, earned release, and/or parole; alternatively, at the discretion of paroling authorities, these individuals

could remain in prison until serving their full terms. Incarcerated persons included in these counts of people with virtual life sentences are:

A. Persons who have been sentenced to 60 years with a parole eligibility after 25 years;

B. Persons who have been sentenced to two separate terms of 25 years, to be served consecutively (i.e., a stacked sentence); or

C. Persons who have been sentenced to a prison term from 40 to 50 years.

Regarding prison populations, states provided us with their prison population as of January 1 in each year. Unlike data provided to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, which requests counts of people held under each jurisdiction and of those sentenced, we requested only a count without specification. The prison population data provided here concerning prison counts allow a reliable comparison to The Sentencing Project data reporting in previous years, but may differ slightly from official statistics offered by the Bureau of Justice Statistics in its Prisoners Series.

Appendix – Survey Instrument

| 1. | In this report, “life” encompasses all three types of life sentences examined in our research: life with the possibility of parole, life without parole, and virtual life sentences, the name given to sentences reaching 50 years or more. When referring to a specific type, we use the precise term. Otherwise, “life” refers collectively to all three. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Some states provided sentence dates instead of offense dates. |

| 3. | Kazemian, L. (2022). Long sentences: An international perspective. Council on Criminal Justice. |

| 4. | Mauer, M. & Nellis A. (2018). The meaning of life: The case for abolishing life sentences. The New Press; Tonry, M. (2008). Learning from the limitations of deterrence research. Crime and Justice, 37(1), 279-311. https://doi.org/10.1086/524825 |

| 5. | Eberhardt, J. L., Goff, P. A., Purdie, V. J., & Davies, P. G. (2004). Seeing Black: Race, crime, and visual processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(6), 876–893. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.6.876; Entman, R. M., & Rojecki, A. (2000). The Black image in the white mind: Media and race in America. University of Chicago Press. |

| 6. | Ghandnoosh, N. (2024). Media guide: 10 crime coverage dos and don’ts. The Sentencing Project. |

| 7. | Tonry, M. (2008). Learning from the limitations of deterrence |

| 8. | Nagin, D. S. (2013). Deterrence in the twenty-first century. Crime and Justice, 42(1), 199–263. https://doi.org/10.1086/670398. |

| 9. | Mauer, M. & Nellis A. (2018). The meaning of life: The case for abolishing life sentences. The New Press; Tonry, M. (2008). Learning from the limitations of deterrence research. Crime and Justice, 37(1), 279-311. https://doi.org/10.1086/524825. |

| 10. | This report uses the terms “juvenile” and “youth” to refer to individuals under the age of 18. |

| 11. | 11 Antenangeli, L., & Durose, M. R. (2021). Recidivism of prisoners released in 24 states in 2008: A 10-year follow-up period (2008–2018). Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 12. | Baay, P. E., Liem, M., & Nieuwbeerta, P. (2012). “Ex-imprisoned homicide offenders: Once bitten, twice shy?” The effect of the length of imprisonment on recidivism for homicide offenders. Homicide Studies, 16(3), 259-279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767912450012; Rhodes, W., Gaes, G., Luallen, J., Kling, R., Rich, T., & Shively, M. (2014). Following incarceration, most released offenders never return to prison. Crime & Delinquency, 62(8), 1003–1025. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128714549655; Roberts, A. R., Zgoba, K. M., & Shahidullah, S. M. (2007). Recidivism among four types of homicide offenders: An exploratory analysis of 336 homicide offenders in New Jersey. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 12(5), 493–507. DOI:10.1016/j.avb.2007.02.012; Shihadeh, E. S., Nordyke, K., & Reed, A.(2014). Recidivism in the state of Louisiana: An analysis of 3- and 5-year recidivism rates among long-serving inmates. Louisiana State University; Liem, M. (2013). Homicide offenders recidivism: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18(1), 19- 25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.08.001; Langan, P.A., & Levin, D.J. (1994). Recidivism of prisoners released in 1994. Bureau of Justice Statistics; Laub, J. H. & Sampson, R. J. (2006). Shared beginnings, divergent lives: Delinquent boys to age 70. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1q3z28f. |

| 13. | Porter, N. & Komar, L. (2023). Ending mass incarceration: Safety beyond sentencing. The Sentencing Project. |

| 14. | Mauer, M. (2003). The meaning of life: Long prison sentences in context. The Sentencing Project; Nellis, A. & King, R. (2009). No exit: The expanding use of life sentences in America. The Sentencing Project; Nellis, A. (2013). Life goes on: The historic rise in life sentences in America. The Sentencing Project; Nellis, A. (2017). Still life: America’s increasing use of life and long-term sentences. The Sentencing Project; Nellis, A. (2021). No end in sight: America’s enduring reliance on life imprisonment. The Sentencing Project. |

| 15. | Ghandnoosh, N. & Budd, K. (2024). Incarceration and crime: A weak relationship. The Sentencing Project. |

| 16. | Van Zyl Smit, D. & Appleton, C. (2019). Life imprisonment: A global human rights analysis. Harvard University Press. |

| 17. | The U.S. Parole Commission estimated having under 150 people serving a parole-eligible sentence in 2023, which is far from the 567 LWP figure provided to us by the Bureau of Prisons for 2024. An explanation for this difference was not available. Caution should be used in interpreting any federal data on persons serving life with parole. See: United States Parole Commission. (2023). Congressional Report FY 2022. |

| 18. | 18 Carson, E. A., Nadel, M., & Gaes, G. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 on state and federal prisons, March 2020 February 2021. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 19. | In Pennsylvania, for instance there has been a large increase in life with parole, from 60 reported people to 239 in 2024. Pennsylvania officials explained that this increase reflects the commutation of persons who were under 18 at the time of their crime, and originally sentenced to LWOP. U.S. Supreme Court rulings invalidated their original sentence (Miller v. Alabama and Montgomery v. Louisiana). Since then, some people have been released and others have been re-categorized as LWP. |

| 20. | Massachusetts’s prison population is disproportionately small in comparison to others. This is because although individuals convicted of felonies are generally sentenced to state prison, not county jail, those with shorter felony sentences (up to 2.5 years) in Massachusetts could serve their time in a county jail. In most states, people with prison terms longer than one year serve their sentences in prison. |

| 21. | In 2024, Iowa, Louisiana, Michigan, and Pennsylvania reported small numbers of individuals serving life with parole sentences, which likely include those whose life without parole sentences were commuted due to recent legal changes regarding their juvenile status at the time of their offenses. |

| 22. | Ghandnoosh, N., Stamen, E., & Budaci, C. (2022). Felony murder: An on-ramp for extreme sentencing. The Sentencing Project. |

| 23. | Simerman, J. & Finn, J. (2023, December 30). On way out, Gov. John Bel Edwards ramps up relief for life prisoners. NOLA. |

| 24. | See Methodology for detailed definition. |

| 25. | Vkiebala & Page, F. (2022, March 23). Virtual life sentences: The least discussed form of death by incarceration. Straight Ahead; F. Page, personal communication, August 28, 2024. |

| 26. | Ghandnoosh, N., Barry, C., & Trinka, L. (2023). One in five: Racial disparity in imprisonment—causes and remedies. The Sentencing Project. |

| 27. | Ghandnoosh, N., Barry, C., & Trinka, L. (2023). One in five: Racial disparity in imprisonment—causes and remedies. The Sentencing Project. |

| 28. | State departments of correction are significantly lagging in separating race from ethnicity within their data. The Sentencing Project mirrors their reporting in an effort to provide a best estimate of Latino people, but acknowledges this is most likely a substantial undercount. |

| 29. | This figure is calculated using the total number of Black individuals serving a life sentence in 2024 and the total number of Black individuals in prison in 2022 (the most recent available year). See: Carson, E. A. & Kluckow, R. (2024). Prisoners in 2022 – Statistical Tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 30. | Spohn, C. (2000). Thirty years of sentencing reform: The quest for a racially neutral sentencing process. Criminal Justice, 3(1), 427-501; Mitchell, O. (2005). A meta-analysis of race and sentencing research: Explaining the inconsistencies. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 21(4), 439-466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-005-7362-7; Steffensmeier, D., Ulmer, J., & Kramer, J. (2006). The interaction of race, gender, and age in criminal sentencing: The punishment cost of being young, black, and male. Criminology, 36(4), 763-797. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1998.tb01265.x; Tonry, M. (2010). The social, psychological, and political causes of racial disparities in the American criminal justice system. Crime and Justice, 39(1), 273-312. https://doi.org/10.1086/653045. |

| 31. | This figure is calculated using the total number of women serving a life sentence in 2024 and the total number of women in prison in 2022 (the most recent year this data was available). See: Carson, E. A. & Kluckow, R. (2023). Prisoners in 2022 – Statistical Tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 32. | Budd, K. (2024). Incarcerated women and girls. The Sentencing Project. |

| 33. | Nellis, A. (2022). Nothing but time: Elderly Americans serving life without parole. The Sentencing Project; Williams B.A., Stern M.F., Mellow J., Safer Guardino M., & Greifinger, R.B. (2012). Aging in correctional custody: setting a policy agenda for older prisoner health care. American Journal of Public Health, 102(8), 1475-81. DOI:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300704. |

| 34. | Franco-Paredes et al. (2021). Decarceration and Community Reentry in the Covid Era. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 21(1), 11-16. |

| 35. | Ghandnoosh, N., Stamen, E., & Budaci, C. (2022). Felony murder: An on-ramp for extreme sentencing. The Sentencing Project. |

| 36. | Lussier, P., McCuish, E., & Jeglic, E.L. (2023). Against all odds: The unexplained sexual recidivism drop in the United States and Canada. Crime and Justice, 52, 1-71. https://doi.org/10.1086/727028; Bureau of Justice Statistics, National crime victimization survey (NCVS), 1993-2021. |

| 37. | Budd, K. (2024). Responding to crimes of a sexual nature: What we really want is no more victims. The Sentencing Project; Cochran, J. C., Toman, E. L., Shields, R., & Mears, D. (2021). A uniquely punitive turn? Sex offenders and the persistence of punitive sanctioning. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 58(1), 74–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427820941172; Kaeble, D. (2021). Time served in state prison, 2018. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 38. | Washington State Legislature. (2002). S. 6151-S, 2nd special session, c. 12, § 320. |

| 39. | Stenberg, R. (2022). A call to abolish determinate-plus sentencing in Washington, Washington Law Review, 97(4), 1219-1282. |

| 40. | Connecticut, Kansas, Maine, Minnesota, Nevada, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Wyoming reported zero individuals serving a life sentence for a drug crime. Virginia did not report offense data. |

| 41. | Alaska, Connecticut, Kansas, Maine, Minnesota, Missouri, Nevada, North Dakota, Ohio, Rhode Island, and West Virginia reported zero individuals serving a life sentence for a property crime. The Federal Bureau of Prisons and Virginia did not provide data on the number of individuals serving a life sentence for a property crime. |

| 42. | Ganeva, T. (2022, September 26). ‘Habitual offender’ laws imprison thousands for small crimes—sometimes for life. The Appeal. |

| 43. | Though most departments of corrections provided age data at time of the offense, some provided age data at time of sentencing. We estimate a one- to two-year difference between these figures, accounted for by the time it takes for a case to move from arrest to conviction. |

| 44. | Nellis, A. & Monazzam, N. (2023). Left to die in prison: Emerging adults 25 and younger sentenced to life without parole. The Sentencing Project. |

| 45. | Feldman, B. (2024). The Second Look Movement: A Review of the Nation’s Sentence Review Laws. The Sentencing Project. |

| 46. | Note: this does not extend to those sentenced to LWOP; Feldman, B. (2024). The second look movement: A review of the nation’s second review mechanisms. The Sentencing Project. |