Effective Alternatives to Youth Incarceration

Report identifies six alternative to youth incarceration program models that consistently produce better public safety outcomes than incarceration, with far less disruption to young people’s healthy adolescent development at a fraction of the cost.

Related to: Youth Justice, Incarceration

Executive Summary

As The Sentencing Project documented in Why Youth Incarceration Fails: An Updated Review of the Evidence, compelling research proves that incarceration is not necessary or effective in the vast majority of delinquency cases. Rather, incarceration most often increases young people’s likelihood of returning to the justice system. Incarceration also damages young people’s future success in education and employment. Further, it exposes young people, many of whom are already traumatized, to abuse, and it contradicts the clear lessons of adolescent development research. These harms of incarceration are inflicted disproportionately on Black youth and other youth of color.

Reversing America’s continuing overreliance on incarceration will require two sets of complementary reforms. First, it will require far greater use of effective alternative-to-incarceration programs for youth who have committed serious offenses and might otherwise face incarceration. Second, it will require extensive reforms to state and local youth justice systems, most of which continue to employ problematic policies and practices that can undermine the success of alternative programs and often lead to incarceration of youth who pose minimal risk to public safety.

This report addresses the first challenge: What kinds of interventions can youth justice systems offer in lieu of incarceration for youth who pose a significant risk to public safety?1 Specifically, it identifies six program models that consistently produce better results than incarceration, and it details the essential characteristics required for any alternative-to-incarceration program – including homegrown programs developed by local justice system leaders and community partners – to reduce young people’s likelihood of reoffending and steer them to success.

Alternative-to-Incarceration Models That Work

This report will describe six program models that show compelling evidence of effectiveness, and also enjoy the backing of energetic organizations dedicated to supporting replication efforts.

- Credible messenger mentoring programs hire community residents with a history of involvement in the justice system who provide intensive support to youth and their families, typically as one part of a multi-pronged intervention.

- Advocate/Mentor programs, such as Youth Advocate Programs, assign trained community residents to work intensively with young people and their families, providing support to the families and helping young people avoid delinquency and achieve goals delineated in their individualized case plans.

- Family-focused, multidimensional therapy models, such as Multisystemic Therapy (MST) and Functional Family Therapy (FFT) employ specially trained therapists who follow detailed protocols to identify and confront factors that propel a young person toward delinquent conduct, with a heavy focus on working with family members to support youth success.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy plus mentors for youth and young adults at extreme risk, like the programs offered by Roca, Inc., engage youth and young adults living in violence-torn neighborhoods who are at extreme risk for future incarceration. Roca youth workers provide participants with cognitive behavioral therapy and connect them with education, employment, and other relevant services.

- Restorative Justice interventions targeting youth accused of serious offenses provide an alternative to traditional court. These programs typically involve victims, and they culminate in a conference where victims, accused youth, and caring adults in their lives meet to discuss the harm caused by the offense and craft plans for the youth to “make things right” and to avoid subsequent offending and achieve success.

- Wraparound programs assign a care coordinator to develop individualized plans offering an array of services to assist children and adolescents with serious emotional disturbances – sometimes including youth facing serious delinquency charges – who might otherwise be placed into residential facilities.

Homegrown Alternatives

Research also finds that locally designed alternative-to-incarceration programs can produce equal or better outcomes than the six models above. These homegrown programs will achieve maximum success if they connect youth with:

- a trusted mentor, advocate, therapist or care coordinator who provides ongoing support and encouragement;

- rigorous and well-designed cognitive behavioral therapies;

- close cooperation with, and support for, young people’s families; and

- constructive education, employment, and recreational or community service activities.

Also, success is far more likely when interventions are sufficiently intensive, tailored to the individual needs and circumstances of the young person and designed to ease the impact of childhood trauma.

Conclusion

Whether they employ one of the six program models profiled here or a well-designed homegrown approach, effective alternative-to-incarceration programs produce better public safety outcomes than incarceration, at far lower costs, and do far less damage to young people’s futures.

Expanding the use of these programs is necessary for youth justice systems to reduce overreliance on incarceration. However, to make a meaningful difference, these programs must be embedded in youth justice systems that strive to steer youth away from more intensive court supervision at every stage of the process and that explore all available options to keep young people at home and in their communities. Youth justice systems must also make concerted efforts to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in youth confinement.

In the end, the most essential ingredient for reducing overreliance on youth incarceration will be a determination to seize every opportunity to keep young people living safely at home with their parents and families, in their schools and communities.

Karemma Williams: A Youth Advocate Program Success story

When Karemma Williams reached high school in 2006, she was bullied due to an autoimmune disease called alopecia, which caused all her hair, even her eyebrows and eyelashes, to fall out. Karemma wore a wig to hide her condition, but it didn’t stop the taunting.

When Karemma Williams reached high school in 2006, she was bullied due to an autoimmune disease called alopecia, which caused all her hair, even her eyebrows and eyelashes, to fall out. Karemma wore a wig to hide her condition, but it didn’t stop the taunting.

So Karemma did what she knew how to do: she fought, and this fighting landed her in the youth justice system repeatedly as a teen on assault charges. Twice, she spent two-week stints locked in detention, an experience she recalls as frightening and dehumanizing – the opposite of what she needed.

“Nobody there cares about you,” she says today. “Nobody teaches you, and the other kids there are scary. You’re just trying to survive.”

Fortunately, Philadelphia’s youth justice system had another answer for Karemma: an alternative to incarceration program operated by Youth Advocate Programs, Inc. (YAP), where she began spending 20-plus hours every week with YAP advocate Tawaina Reed and a group of other girls also under Reed’s supervision.

Today, Karemma credits the YAP program with turning her life around. “I just needed someone to understand me and to listen to me,” she recalls.

“Karemma was very angry at first,” Reed recalled recently. “She would be snappy for every little thing. That was her defense mechanism. She was always in survival mode. But I could see underneath, she was the sweetest person.”

Karemma and the other girls in the YAP program spent time together doing homework, participating in recreational activities (bowling, fashion shows, cinema, skating, miniature golf, and more), visiting halfway houses and doing community service projects, sharing meals, and talking about their issues and challenges.

Reed created an emotional safe space for the YAP participants. Over time, Karemma let her guard down and lost the impulse to prove herself to kids who teased her, or to fight them.

“I was really comfortable around her,” Karemma recalls. “I started to feel really confident.”

Today, Karemma is a blogger, life coach, and interior designer. Recently she moved away from Philadelphia to begin a new life in Arizona. “I feel like I went from zero to 100,” she says. “I feel very successful.”

Introduction

By now the verdict is clear. Any objective reading of the evidence shows beyond a reasonable doubt that incarceration is neither necessary nor effective in the vast majority of cases of adolescent lawbreaking. On the contrary, as The Sentencing Project documented in Why Youth Incarceration Fails: An Updated Review of the Evidence, removing youth from their homes substantially increases the likelihood that they will return to the justice system on new charges. Incarceration also damages young people’s futures, exposes many already traumatized youth to abuse, and contradicts the clear lessons of adolescent development research. And because of continuing system biases, these harms of incarceration are inflicted disproportionately on Black youth and other youth of color.

This report examines the obvious follow-up question: If not incarceration, what? What programs can be used to safely supervise youth who commit serious offenses and pose a significant risk of reoffending and endangering public safety, and to steer them away from delinquency?

The report begins by reviewing the evidence showing the poor outcomes of youth incarceration, and some of the reasons why youth incarceration fails. Next the report identifies several strategies that have shown a positive impact on adolescent offending – and particularly on reducing reoffending rates of youth who have previously engaged in delinquent conduct. It then documents the evidence supporting six multifaceted intervention models that have demonstrated effectiveness as alternatives to incarceration for youth following adjudication. (See below on why this report focuses less on pre-trial detention.) None of the models highlighted here are guaranteed to prevent reoffending by all youth, or by any particular young person, nor should they be expected to do so. But the evidence shows that all six are significantly more likely than incarceration to reduce reoffending behaviors, enhance public safety, and increase young people’s future success.

Finally, the report briefly touches on state and local justice system reforms that are necessary to support the implementation and widespread utilization of effective alternative-to-incarceration programs, and to minimize the use of incarceration for youth who do not pose a serious or immediate threat to public safety.

Despite a large drop over the past two decades, the number of youth in correctional custody remains far too large: At last count, fewer than one-third of youth in correctional custody were incarcerated for serious violent felonies. Many significant opportunities remain for state and local youth justice systems to further reduce reliance on incarceration in ways that protect the public and enhance young people’s well-being. Pursuing these opportunities – ending the wasteful, unnecessary, counterproductive, racially unjust, and often abusive confinement of adolescents – should be a top priority of youth justice reform nationwide.

Why This Report Focuses on Minimizing Correctional Incarceration, Not Pre-Trial Detention

This report largely focuses on correctional confinement, after youth have been found delinquent in court, but not on pre-trial detention when youth may be confined pending their hearings in court. Reducing the use of pre-trial detention is critically important because of the long-term damage that even short stays in detention can have on young people’s futures. However, reforming detention practices has been the focus of the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative for the past 30 years.2 Therefore, rather than focusing extensively on detention, the report concentrates on best practices for reducing incarceration following adjudication and for providing effective alternative-to-incarceration programming, which have not received as much attention previously, and have not been as well-documented or widely embraced.

Research Review: Why Not Incarcerate Youth?

Nearly 25 years ago, youth justice scholar Barry Feld wrote: “A century of experience with [youth correctional facilities] demonstrates that they constitute the one extensively evaluated and clearly ineffective method to treat delinquents.”3 Since then, several research findings have been documented even more conclusively.

Incarceration does not reduce delinquent behavior

Youth released from correctional facilities experience high rates of rearrest, new adjudications (in juvenile court), and reincarceration.4 Meanwhile, an alarming share of young people released from correctional facilities are later arrested, convicted, and incarcerated as adults.5 And research controlling for young people’s offending histories and other relevant characteristics typically finds that confinement leads to equal or higher rates of rearrest and reincarceration than probation and other community alternatives to confinement.6

Pre-trial detention increases subsequent involvement in the justice system

Incarcerating youth in secure detention facilities pending their court adjudication hearings (akin to trials in adult criminal court) significantly increases the odds that youth will be placed in residential custody if a court finds them delinquent. Spending time in detention also increases the likelihood that youth will be arrested and punished for subsequent offenses.7

Incarceration impedes young people’s success in education and employment

Incarceration makes it less likely that young people will graduate from high school, reducing college enrollment and completion rates, and lowering employment and earnings in adulthood.8

Incarceration damages young people’s health and well-being

It leads to poorer health in adulthood, thereby exacerbating the serious physical health problems and mental health challenges suffered by many youth who enter juvenile facilities.9

Juvenile facilities are rife with maltreatment and abuse

Systemic or recurring abuses were documented in state-funded youth correctional facilities of 29 states and the District of Columbia between 2000 and 2015,10 and alarming new revelations of pervasive abuse have emerged in several states since 2015.11

Racial and ethnic disparities in incarceration are vast and unjust

Black youth and other youth of color are incarcerated at far higher rates than their white peers.12 Studies consistently find that disparities at detention are driven, at least in part, by biased decision-making. For incarceration after youth are found delinquent, disparities are exacerbated by biased decision-making in detention as well as other early stages of justice system involvement (arrest, formal processing in court).13

Incarceration interferes with healthy adolescent development

The human brain does not fully mature until at least age 25, and this lack of maturity makes lawbreaking and other risky behaviors more common during adolescence.14 Yet, as their brains develop, the vast majority of youth age out of lawbreaking.15 Young people’s ability to desist from delinquency is tied to their progress in learning to control impulses, delay gratification, weigh the consequences of their actions, consider other people’s perspectives, and resist peer pressure.16 New research finds that incarceration slows this maturation process, undermining young people’s abilities to embrace positive behavior change and desist from delinquency.17

Incarceration often backfires by traumatizing already traumatized young people

Youth who become involved in the juvenile justice system are several times more likely than other youth to have suffered traumatic experiences,18

and research finds that exposure to multiple types of trauma can impede children’s healthy brain development, harm their ability to self-regulate, and heighten the risks of delinquent behavior.19 Incarceration is itself a traumatic experience for young people, and it can exacerbate the difficulties faced by youth who have previously been exposed to trauma – and heighten their likelihood of reoffending.20

While there will likely always remain a small population of youth who pose an urgent threat to public safety and therefore have to be incarcerated, the evidence is overwhelming that, in the vast majority of delinquency cases, incarceration is counterproductive.

Sheldon Smith-Gray: Turning His Life Around With Roca, Inc.

Were it not for Roca, Inc., Sheldon Smith-Gray says, “who knows what I might have been?”

Were it not for Roca, Inc., Sheldon Smith-Gray says, “who knows what I might have been?”

Sheldon grew up in Baltimore, graduated from high school and enrolled in some college-level nursing classes. But academic achievement wasn’t his primary interest. Smith-Gray started selling drugs as a teenager, and in a recent interview, he recalled dreams of being the biggest drug dealer in all of Baltimore.

Unlike many of his peers, Smith-Gray somehow managed to avoid getting arrested or prosecuted before age 18. But, he admits, “I did a lot of things I shouldn’t have done.”

Now all that is behind him. Instead, these days Smith-Gray is employed as a youth worker for Roca, the program that he says “changed my life.”

Roca works with many 16- and 17-year-olds, but it wasn’t until Smith-Gray was 20 that Roca youth workers started knocking on his door, just days after he returned home from his second stint in the local jail – this time on a probation violation tied to an earlier gun possession charge.

Initially Smith-Gray resisted, but following the organization’s motto of “relentless outreach,” members of the Roca team kept knocking, and eventually he let them in. Smith-Gray remained skeptical, “But they showed me. Everything they said they would do, they did. Everything they promised, they stood on it.”

The Roca youth workers “came from where I came from,” he recalls, and he started to think, “If they can make themselves into respectable people like this, so can I.”

Through Roca, Smith-Gray received tangible support: employment opportunities, job readiness training, parenting skills, money management, and more. But more important, he says, were the thinking skills that youth workers constantly drilled into him, following Roca’s customized cognitive behavioral therapy curriculum, Rewire CBT.

“The skills give you the ability to step back and think,” he says. “‘Is this worth it?” Do I want to go to jail? How will this affect my family?’”

“It wasn’t until I was 23 that I figured out that those skills work,” he says.

Now as a Roca staff member, Smith-Gray teaches those same skills to many youth caught up in Baltimore’s gun violence epidemic .

“I call this righting my wrongs,” he says.

What Works to Reduce Youth Offending?

Forty years ago, the fields of criminology and adolescent development research offered few practical answers for policymakers on how best to respond to delinquent conduct.21 Since then, however, scholars have uncovered a wealth of new evidence on what works to combat delinquency.22 This new knowledge offers valuable lessons regarding how our society and our justice systems can best respond when youth have engaged in lawbreaking behavior.

The first lesson is that removing young people from their homes and communities, placing them in institutions, is ineffective. The most recent review of juvenile justice research by the National Academies of Science noted that placement in correctional institutions tends to be less effective than multifaceted community-based interventions: “well-designed community-based programs are more likely than institutional confinement to facilitate healthy development and reduce recidivism for most young offenders.” Further, the National Academies found that “these effects can be found even when these interventions are applied in community settings with relatively high-risk adolescents.”23 Indeed, the evidence shows that incarceration usually does more harm than good both for public safety and for young people’s future success and well-being; incarceration should therefore be used only in cases where young people pose an immediate threat to public safety.8

In General, What Works to Reduce Delinquency?

The next lesson emerging from research is that several types of interventions have clearly demonstrated effectiveness in reducing young people’s likelihood of reoffending, while other intervention strategies show significant promise as well. These proven and promising intervention strategies, all of which can be utilized in a successful alternative-to-incarceration program, include:

- Cognitive-behavioral skill-building. A wealth of research finds that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) programs are among the most effective strategies to reduce reoffending for both youth and adults involved in delinquent or criminal conduct, with “significant positive effects on recidivism.”25Delivered either in institutional or community settings, typically in a series of 20 to 30 sessions over a period of up to 20 weeks, these programs offer lessons, role-playing exercises, and other activities to help participants recognize and change unhealthy thinking patterns and embrace alternative behaviors.

- Mentoring. Research finds that, in general, mentoring programs which assign adults to spend time with youth at risk of delinquency, or youth already involved in the justice system, tend to have small but positive impacts on reducing delinquent conduct.26 More intensive interventions, employing paid and specially trained mentors (sometimes called “credible messengers” or “advocates”) who hail from the same communities as the youth they serve and who often have personal experience in the justice system, have proven particularly effective in reducing recidivism.27

- Family counseling and support. Overwhelming evidence shows that parents and families continue to exert enormous influence on their adolescent children, and interventions that work with family members and target the family environment are among the most effective intervention types for addressing behavior problems and reducing reoffense rates of court-involved youth.28 Several carefully designed family-focused treatment models have significantly reduced reoffending in many evaluation studies.29

- Positive youth development opportunities. For youth who are not incarcerated, the youth justice system’s responses to delinquent conduct typically emphasize compliance monitoring (probation) and therapeutic treatment to address a young person’s problems or deficits. However, a growing body of research suggests that youth in the justice system can also benefit from constructive activities in the community geared toward building on their strengths, connecting them to caring adults, and teaching them new skills. These programs also help young people develop a sense of belonging, exercise leadership, and contribute to their communities.30 Evaluations measuring the impact of positive youth development programs on delinquency are limited, but several studies show positive effects,31 and a vast body of research shows that positive youth development programs help young people improve their school attachment, academic success, self-esteem, problem-solving skills, and more.32

- Tutoring and other support to boost academic success. Academic failure is a critical risk factor for delinquency.33 To improve academic success and thereby reduce the likelihood that youth will enter the justice system, studies find that two types of interventions are highly effective. Intensive tutoring programs for students at high risk of school failure can significantly boost academic success and reduce the share who drop out; these programs are also associated with lower arrest rates.34 Additionally, legal advocacy on behalf of students with educational disabilities can significantly boost school success rates and lower the likelihood of future arrests.35

- Employment and work readiness. Studies show that providing work experience and job readiness training to youth can boost their odds of success and lower subsequent offending rates, but only if they are carefully designed and well-targeted.36 Indeed, some research has found that adolescent employment programs – especially if they target younger youth or provide too many hours (and therefore conflict with school success) – can actually increase offending rates.37 However, many studies find that better-designed employment programs reduce reoffending.38 For instance, YouthBuild, a year-long program that combines academic education, life-skills instruction, and training in building trades, leads to less recidivism than traditional court processing, and at far lower cost.39

- Wraparound care. Wraparound programs offer coordinated care for children and adolescents with serious emotional disturbances who might otherwise require placement into residential facilities. Funded through a “systems of care” arrangement that blends funding from a variety of public systems (child welfare, juvenile justice, adolescent mental health, education), the wraparound approach has grown increasingly widespread over the past two decades and has demonstrated success in improving youth well-being and preventing out-of-home placements.40 Though wraparound has not been used widely for youth facing serious delinquency charges, several studies show that wraparound programs for youth involved with delinquency courts can lower offending rates and vastly reduce the use of confinement or other out-of-home placements.41

- Restorative justice. Restorative justice programs provide an alternative to traditional court processing, focusing on repairing the harm caused by an offense rather than solely ascertaining guilt and punishing the person responsible. These programs may involve mediation or a conferencing process led by expert facilitators where the youth, victim, and important people in their lives meet to discuss the harm caused by the offense and craft a plan to repair the harm and to provide the young person with support and assistance to reduce the likelihood of reoffending. Meta-analyses of evaluation research show that restorative justice programs for youth produce lower rates of recidivism than traditional court processing.42

While each of these intervention types improve outcomes for justice-involved youth, the evidence does not indicate that any single type of intervention (unless it is comprehensive and multidisciplinary, such as wraparound care or multidimensional family-focused therapy) will likely be sufficient on its own to maximize the odds of success for a young person at high risk of reoffending. Rather, research and practical experience indicate that the most effective strategies for youth at high risk of reoffending will layer or braid together a variety of supports, services, and opportunities tailored to the individual needs and circumstances of each young person.

Research also makes clear that success is far more likely when interventions for youth with serious needs and high risk of reoffense are delivered with sufficient intensity to impact the young person’s behavior,43 “trauma-informed” in ways that ease rather than exacerbate the impact of childhood trauma the young people have experienced,44 and responsive to young people’s learning styles, to maximize the likelihood that youth will fully participate and benefit from the supports and services provided.45

No program model, however comprehensive and well-run, can succeed with all young people all of the time. There are no magic wands. Yet there is powerful evidence to suggest that alternative-to-incarceration programs which include these elements and adhere to these principles produce better public safety outcomes than incarceration and do far less damage to young people’s futures. And they do so at far lower cost than incarceration.

Alternatives to Youth Incarceration: Effective Models and Principles for Success

Many juvenile court jurisdictions operate one or more alternative-to-incarceration programs for youth at risk of being removed from their homes and placed in correctional institutions or other residential facilities. Research shows that, on average, home-based programs yield equal or better recidivism outcomes than incarceration, with far less disruption to young people’s healthy adolescent development, and at a fraction of the cost for taxpayers.46 However, few alternative-to-incarceration programs have been rigorously evaluated, leaving many programs without the evidence needed to prove their positive impact. Still fewer program models have had their methods and protocols documented carefully for other jurisdictions that might be interested in replicating their approaches.

The six models described here have demonstrated compelling evidence of effectiveness, and all have the backing of energetic organizations dedicated to supporting replication efforts.

- Credible messenger mentoring programs, in which community residents with lived experience in the justice system provide intensive support to youth, typically as part of a multifaceted alternative-to-incarceration intervention.

- Advocate/Mentor programs such as Youth Advocate Programs (YAP), especially when combined with advanced cognitive behavioral therapy.

- Family-focused, multidimensional therapy models, such as Multisystemic Therapy (MST) and Functional Family Therapy (FFT).

- Cognitive behavioral therapy along with mentors for youth and young adults at extreme risk, such as Roca, Inc.

- Diversionary restorative justice interventions targeting youth accused of more serious offenses who might otherwise be placed in facilities.

- Wraparound care for youth with serious emotional disturbances, such as Wraparound Milwaukee.

Credible Messenger Mentoring Programs

Overview: This model employs community residents with a history of involvement in the justice system to provide intensive support and assistance to youth and their families. This approach, typically one part of a comprehensive intervention, aims to help young people avoid reoffending while achieving goals important to their personal development and well-being. Two evaluation studies of programs in New York City that employ credible messengers found that the interventions substantially reduced reoffending rates.47 While a similar program in Washington, DC, has not been formally evaluated, its outcomes are favorable and have been a key element of the District’s success in dramatically reducing juvenile incarceration in recent years.48

Core elements and variations on the model: The term “credible messengers” refers to individuals who live in the neighborhoods where the programs operate (often areas with concentrated poverty and high rates of crime); these individuals share many characteristics with participating youth, including a history of involvement in the justice system. Credible messengers often facilitate group activities aimed at teaching youth cognitive behavioral skills. They also spend considerable time individually with the young people and make themselves available 24/7 to help youth build motivation and achieve their personal goals, and to deal with any crises that may arise. In addition, credible messengers advocate for the young people in court and with school and probation personnel, and provide support and encouragement to the young people’s families.49

Clinton Lacey, who developed the two New York City programs as deputy director of the NYC Department of Probation, and who then oversaw the development of the program in Washington, DC, explains that the credible messengers approach (also known as transformative mentoring) is best understood not as a program in itself, but rather as an invaluable extra ingredient – “the glue” – in a comprehensive intervention. In many programs, youth and their families work with the credible messenger to develop an individualized success plan which may include continuing probation or correctional supervision, educational support, employment opportunities and job readiness training, positive youth development programming, substance abuse and mental health treatment, and family counseling.50 While credible messenger programs share these common ingredients, they may differ in important respects.

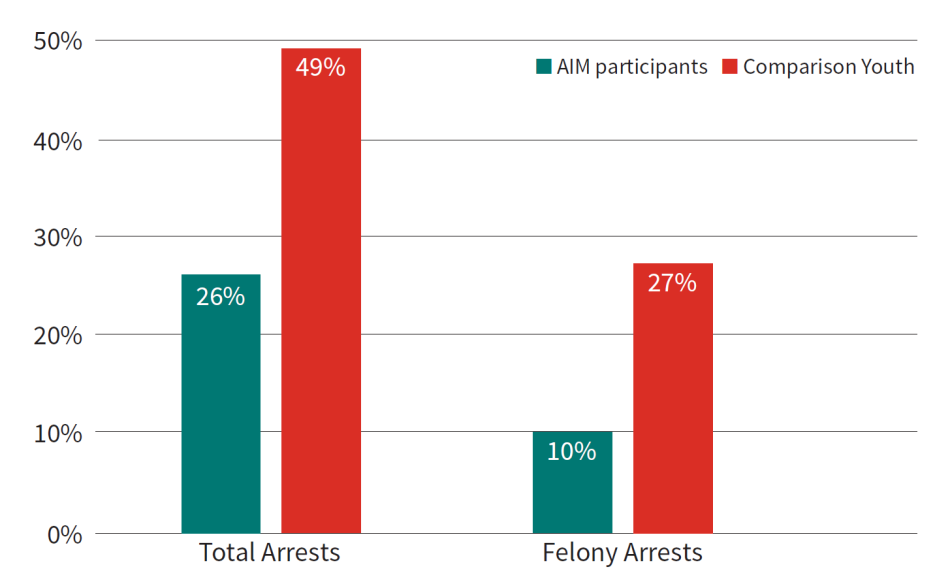

- In New York City, the Advocate, Intervene, Mentor (AIM) program works with 13- to 18-year-old youth on probation who score as high risk for reoffense51 and would otherwise be placed in facilities subsequent to a new felony offense or repeated failures on probation. Once enrolled, a “family team” including the youth, family members, probation officer, and credible messenger develops an individual plan with goals and related action steps for the young person during the 6- to 9-month AIM program period.52

- New York City’s Arches Transformative Mentoring program works with 16- to 24-year-olds on probation. Unlike the AIM program, where mentors’ work with youth is mostly one-to-one, Arches is primarily a group program in which participating youth and young adults attend group mentoring sessions facilitated by credible messengers, following a 48-session curriculum that relies on interactive journaling to develop important cognitive behavioral skills. Participants receive stipends to attend the sessions. In addition to helping facilitate the group journaling sessions, credible messengers also meet individually with participants to reinforce the group lessons and heighten young people’s motivation to avoid further offending and pursue positive goals. Typically, participants complete the program in 6 to 12 months.53

- In Washington, DC, credible messenger mentors provide group and individual activities for youth committed to the District’s Department of Youth Rehabilitation Services (DYRS), including some youth who are permitted by DYRS to remain at home in a community commitment status (an alternative to incarceration).54 Unlike the New York City programs, the DYRS Credible Messenger Initiative assigns two mentors for every youth – one to the young person and another to the family – and the mentors also work with the siblings of program participants to prevent their involvement in delinquency. Also unlike the New York City programs, the credible messengers in Washington, DC, have offices and work alongside correctional agency staff, and they participate in the initial case planning process, family team meetings, and virtually all other meetings between youth and DYRS staff.55

Evidence of effectiveness: An evaluation of New York City’s AIM program found that just 20% of the participants, all of whom would have been incarcerated if not placed into the AIM program, were incarcerated because of a new offense during the program period. In the year after enrolling in AIM, 77% of participants remained arrest-free and just 11% were arrested for a felony.56 The reoffending rates were far lower for AIM participants than for youth released from facilities before the inception of the AIM program.57 The evaluation also found that most AIM participants made significant progress on a range of youth well-being measures, and that success was highly correlated with the amount of time youth spent participating in program activities with their credible messenger mentors.58 An evaluation of New York’s Arches program found that, for the total program population (ages 16 to 24), participants were less than half as likely as a matched comparison group to be convicted of a new felony both 12 months and 24 months after beginning probation. The results were especially strong for younger participants. Compared with youth in a comparison group, Arches participants under age 18 were 68% less likely to be convicted of a new felony within 24 months.59

In Washington, DC, the credible mentor program operated by DYRS for youth at home in community commitment status has not been rigorously evaluated. However, a qualitative study by scholars at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice found that, “without exception,” youth involved in the DC Credible Messenger program spoke positively about the impact of credible messenger mentors, reporting that mentors made a difference in their self-confidence, attitudes toward education, coping skills, relationships with their families, feelings about their communities, and attitudes about the future.60 Parents and other family members also found the credible messengers “extremely helpful.”61 DYRS data show that the addition of credible messengers improved the system’s outcomes. In the six years before credible messengers were introduced in 2015, the recidivism rate for youth committed to DYRS custody averaged 35.8%; since then (fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2021), the recidivism rate averaged 21.5%,62even though the share of youth committed for felony offenses increased.63

FIGURE 1. NYC’s AIM Program Reduced Recidivism

Results after 12 months

Comparison Youth” were placed in locked facilities prior to the launch of the AIM Program.

Status of and support for replication efforts: In March 2021, Clinton Lacey left DYRS to found a new organization, the Credible Messenger Mentoring Movement (CM3), dedicated to replicating the credible messenger model in jurisdictions throughout the U.S. As of early 2023, the CM3 is supporting credible messenger alternative-to-incarceration program replication efforts in Atlanta, GA; Chicago, IL; Houston, TX; New Orleans, LA; Birmingham, AL; Bridgeport, CT; Columbus, OH; Jackson, MS; Jersey City, NJ; Orlando, FL; and multiple sites in Washington State. CM3 is also supporting credible messenger programs within correctional facilities in Los Angeles County, South Carolina, and Oakland, Calif.64 A number of other jurisdictions – including Maine, Milwaukee, and San Diego – are also exploring credible messenger mentoring programs for youth in the justice system.65

Mentor/Advocate Programs

Overview: Founded in 1975, Youth Advocate Programs, Inc. (YAP) is a Pennsylvania-based nonprofit organization that operates programs to prevent out-of-home placements for nearly 18,000 youth and young adults per year in more than 100 jurisdictions nationwide.66 Though YAP programs often work with other populations (those in the child welfare/foster care system, youth with disabilities, youth attending public schools in disinvested communities, and youth in other stages of the justice system), some YAP programs are designed as alternatives to incarceration for youth found delinquent in court. While few of those programs have been evaluated rigorously, the available evidence suggests that they are effective in helping youth remain safely in the community.67 A 2020 study found that a Chicago program combining YAP’s standard program with enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy substantially reduced reoffending rates and improved school attendance and behavior.68

Core elements and variations on the model: At the beginning of the YAP process, program staff work together with the young person and their family to develop an individual plan that identifies goals the young person will seek to accomplish during the program period. YAP then assigns a community resident, recruited and trained by YAP to work intensively with each young person and their family, typically for 10 hours per week or more, to provide guidance and encouragement to support the family and help the young person avoid delinquency and achieve their case plan goals. The advocates make themselves available on a 24/7 basis to address any crises, and YAP makes available flexible funds to address any important needs or opportunities that may arise – anything from a new tire for the family car to new sports equipment or art supplies for an afterschool program. Finally, YAP offers subsidized employment opportunities that enable young people to gain work experience and earn extra money to meet basic needs.69

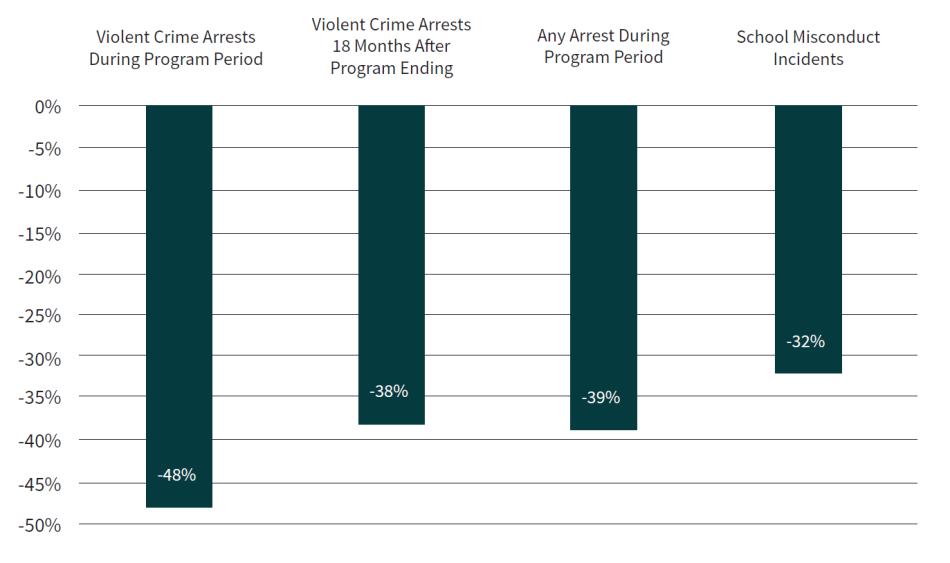

In 2015, YAP began working on a new hybrid program in Chicago called Choose to Change, which combines YAP’s standard model with a series of 16 trauma-informed cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) sessions delivered by trained therapists employed by Children’s Home & Aid, a community-based social service organization. YAP advocates participate in the CBT sessions and then reinforce the lessons in their regular interactions with participants.70

Evidence of effectiveness: In a 2014 study, scholars at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice examined YAP’s impact on over 3,500 adolescents referred from the justice system, of whom 30% had been adjudicated for felonies and 21% had been removed from their homes at least once prior to entering the YAP program. The study found that 86% of these youth were not arrested during their time in the program, and 7% were removed from their homes while participating in YAP.71 In four Alabama counties where YAP operated alternative-to-incarceration programs, 87% of the 220 youth completing the program from 2011 through 2013 remained arrest-free during the program; just 35% remained under court supervision at the end of the program (whereas 79% had been under court supervision upon entering YAP).72

FIGURE 2. YAP Participants Reduced Recidivism, Improved School Outcomes Results

during program vs Control Group

Choose to Change participants receive usual YAP services combined with intensive cognitive behavioral therapy.

More recently, a study evaluated six new YAP alternative-to-incarceration programs serving youth with significant offending histories: roughly half of the youth had previously been adjudicated for a felony offense or faced new felony charges, and in most sites a majority of participants had experienced previous out-of-home placements. Most participants (83%) remained at home at the end of their participation in YAP, and less than 10 percent were adjudicated for a new offense while participating in the program. In addition, YAP increased the share of youth who were on track in school, and the share of youth working in paid jobs, internships, or community service rose by 50 percent.73

Finally, a preliminary evaluation found that the Choose to Change program in Chicago reduced violent crime arrests by 48% during the program period, and most of this difference persisted in the 18 months after discharge from the program. The study, which involved random assignment (the gold standard for this type of research), also found that participants were one-third less likely than a control group to suffer any arrest two-and-a-half years after leaving the program. After beginning the program, participants attended more school days than control group youth did, and they were less likely to be cited for misconduct at school.74

Status of and support for replication efforts: Nearly 40 years after its founding, YAP continues to vigorously promote its model and work to expand the program’s reach. This includes a continuing commitment to support local YAP programs that serve as alternatives to both pre-trial detention and long-term placement following adjudication. YAP programs that serve as alternatives to long-term custody now operate in over 100 sites nationwide.75

Evidence-Based, Family-Focused, Multidimensional Therapy Models

Overview: In family-focused therapy models such as Multisystemic Therapy (MST) and Functional Family Therapy (FFT), as well as several other models that are less widely replicated, therapists work closely with the family and strive to identify and address the multitude of factors that propel the young person toward delinquent conduct.76 Both MST and FFT have been found to be highly effective in many evaluation studies,77 and both are used by dozens of jurisdictions across the nation as an alternative to placement in facilities for youth with significant offending histories.78

Core elements and variations on the models: In MST, specially trained therapists typically meet with youth and their families at their homes, or in the community, and maintain frequent contact as they seek to identify problems in the family, peer group, school, and neighborhood that might be causing behavior problems. To address the identified problems, MST therapists work with the youth and family to develop and test individualized intervention strategies to promote the young person’s success. MST involves family members closely in all interventions and seeks to help build the family’s motivation and capacity to support the young person’s success. Treatment is usually completed in three to five months.79 By contrast, FFT is typically delivered in an office setting, supplemented by home visits, with the young person and at least one parent or guardian, usually in 12–16 sessions over three or four months. The therapy process involves five phases: engagement, motivation, relational assessment, behavior change, and finally, generalization to sustain progress and forge connections with helpful resources in the community.80

Evidence of effectiveness: FFT has been evaluated in 75 research studies dating back to 1973, many of which show that it produced far lower recidivism than probation or other justice system interventions.81 MST has been the subject of 96 evaluation studies, including 19 studies measuring MST’s effectiveness for court-involved youth with serious offenses and 19 more for youth with serious conduct problems.82 The studies found that MST programs for youth with serious offenses reduced long-term rearrest rates by 42% on average, compared with probation, residential confinement, and other alternatives.83 Across outcomes studies of MST with all high-risk youth populations (including youth with mental health conditions, youth who were victims of neglect and abuse, and youth involved in sexual offenses), studies found that MST reduced out-of-home placements by 54%.84

Some have challenged the research on MST and FFT by noting that, in many studies, the programs under study were supervised by the models’ developers rather than by state and local agencies or community providers in typical real-world conditions, and that many studies were conducted by the scholars associated with the model’s development and replication.85 However, several organizations have identified both FFT and MST as evidence-based interventions.86 For instance, FFT and MST (as well as a specialized version of MST focused on youth with problematic sexual behavior[s]) are among the only juvenile justice interventions to meet the exacting standards required to be named as a model program under the University of Colorado’s highly regarded Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development initiative.87

Status of and support for replication efforts: Both FFT and MST have dedicated organizations working to support replication efforts throughout the US and around the world. FFT LLC employs several dozen trainers to support FFT replication efforts, and it reports that FFT programs currently operate in 45 states and 10 foreign countries, with 310 treatment teams serving 40,000 youth per year.88 MST Services employs more than three dozen trainers and other staff members, and it lists nearly 600 program sites worldwide operating in more than 35 states and 16 other nations.89 Both organizations offer training, support, quality assurance, and coaching for local entities seeking to develop new programs and to ensure that the therapies are replicated with fidelity to the original models.

Roca, Inc. – Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Mentors for Youth and Young Adults at Extreme Risk

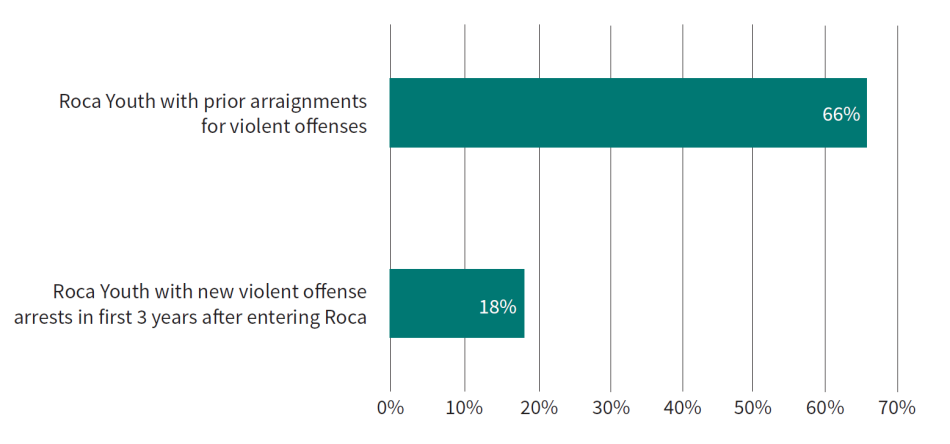

Overview: Unlike the other models highlighted here, Roca, Inc. (Roca) does not primarily serve youth referred from the justice system as part of the court process. Rather, Roca intervenes on its own initiative in the lives of youth living in violence-torn neighborhoods who are at extreme risk for future incarceration. Through a four-phase intervention that can last up to four years, Roca youth workers go into the community and engage participants, train them using Roca’s tailored cognitive behavioral therapy treatment model, and connect them with education, employment, and other relevant services. Available data and evaluation research show that, through this unique model, Roca is successfully engaging youth and young adults at the center of urban violence, many of them gang-involved, and substantially reducing their likelihood of arrest and incarceration.

Core elements of the model: Roca operates programs for young men in five Massachusetts locations and in Baltimore. The programs target 16- to 24-year-olds who have a history of arrest, incarceration, violent behavior, gang involvement, or disconnection from education and work and who, in Roca’s words, are “not ready, willing, or able to participate” in more traditional programs or services.90 Roca also operates programs for young mothers in several Massachusetts locations and in Hartford, CT. Roca operates its programs with a mix of public and private funding, and participation in the program is voluntary, not mandated. Participants are referred from a wide variety of partner organizations including police, probation, corrections, and other public agencies, or through Roca’s own street outreach.91

The first of the four phases in the Roca model, “Building Trust,” involves what the organization calls “relentless outreach” by trained youth workers to engage the identified young people in their homes and communities – continually knocking on the young people’s doors, and those of their friends and families, until the youth agree to participate. The second phase, “Behavior Change,” focuses on teaching cognitive behavioral therapy skills using Rewire CBT, a curriculum specially designed by Roca and Massachusetts General Hospital, which can be taught individually, on an ad hoc basis, rather than in scheduled group lessons (as is done in most CBT programs). Roca youth workers also mentor participants and connect them to education, workforce readiness training, and subsidized work in Roca’s transitional employment program.92

A final noteworthy element of Roca’s model is the unusual financing mechanism – “social impact bonds” – used to support Roca programs in Massachusetts. In this “Pay for Success” initiative, private investors have contributed money to support Roca’s program costs, and the state has agreed first to have criminal justice agencies refer high-risk participants to Roca and second to reimburse Roca and its investors based on the program’s success in reducing participants’ incarceration rates. Specifically, the state agreed to refer 1,300 youth to Roca for the period from 2014 to 2023, and to pay Roca up to $32 million based on the savings achieved by reducing the time participants spend in correctional facilities, which cost $55,000 per individual per year.93

Evidence of effectiveness: In Massachusetts, 80% of the young men participating in Roca’s programs from 2018 to 2020 had been arrested for felonies. Most had been incarcerated, and half or more were involved in gangs or selling drugs. Yet just 29% of these young men were incarcerated within three years of beginning Roca94 – a rate far lower than the three-year reincarceration rates for similar young adults released from the state’s jails (52%) and prisons (56%).95 Also, whereas two-thirds of Massachusetts participants had been arrested for violent offenses before entering the Roca program, fewer than one in five recidivated for a violent offense within three years.96 In Baltimore, of the 352 young people Roca served in 2022, 98% had a history of prior arrests, but only 28% were arrested during their first two years in the Roca program; and 95% of participants were not incarcerated for a new offense during their first two years.97

Status of and support for replication efforts: The Roca Impact Institute, the intensive coaching arm of Roca, provides support to community violence intervention efforts, probation agencies, corrections departments, law enforcement agencies, and community-based organizations across the country.98 Though the organization’s leadership originally sought to help other jurisdictions replicate Roca’s full intervention model, it found that, in the words of Roca Executive Vice President Jennifer Clammer, who oversees the Impact Institute, supporting full replication “turned out to be very difficult to do from afar.”99 As a result, the Roca Impact Institute now focuses most of its efforts on teaching personnel in interested sites to master Roca’s Rewire CBT curriculum. The Impact Institute also supports some sites in adapting other elements of the Roca model in ways that suit local circumstances.100

FIGURE 3. Roca Gets Results in Massachusetts

Youth Far Less Likely to be Arrested for Violent Offenses After Enrolling

Diversionary Restorative Justice Conferencing

Overview: Restorative justice provides an alternative to traditional court processing that focuses on repairing the harm caused by an offense rather than solely ascertaining guilt and punishing the person responsible. The process typically involves the person(s) harmed and the youth who committed the offense, as well as other important people in the lives of both youth and victim. The process culminates in a conference where the victim and the youth meet, discuss the harm caused by the offense, and then craft a plan for the youth to “make things right” and to support the young person in avoiding subsequent offending and achieving success.

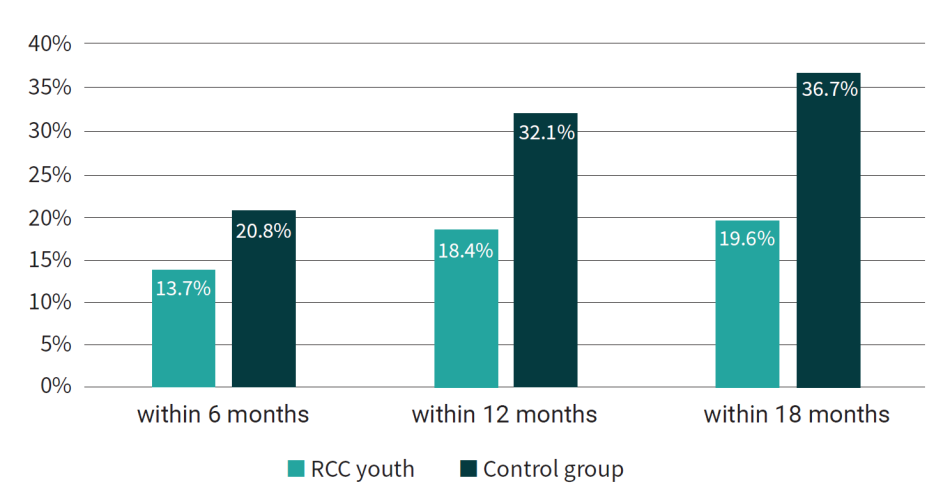

Though most restorative justice programs to date have focused on youth and adults accused of minor offenses, some jurisdictions have employed restorative justice as an alternative to incarceration for youth and young adults accused of serious offenses. Recent studies find that these programs – which divert participants from the court process entirely – can reduce the reoffending rates of youth accused of more serious offenses while keeping them at home, and also enhance victims’ satisfaction with the justice process.

Core elements and variations on the model: Impact Justice, a justice reform organization with offices in Oakland, Calif., and Washington, DC, leads a network of restorative justice conferencing programs across the nation that work with youth involved in felony offenses and high-level misdemeanors that might otherwise result in confinement.101 Impact Justice’s online toolkit explains that restorative justice conferencing is best suited to cases involving a serious offense where a person has been harmed and where there is no question about who is responsible.102 (The process is not appropriate in cases where the young person denies responsibility.)

The Impact Justice toolkit describes three stages of the restorative justice conferencing process.103

- In the Preparation Stage, program staff reach out and build relationships with the victim(s) and with the young person responsible, as well as their family members, and other people in the young person’s life (caregivers, mentors, supporters) whom the young person wishes to participate in the restorative justice conference. The youth is asked to reflect on the harms caused by the offense and to write a letter of apology to the victim. Staff ask the victim(s) to reflect on the harms caused by the offense, and they also engage family members and other people whom the victim wishes to participate. In a series of meetings that may take several months, the program staff familiarize all participants with the goals of the process that will be followed during the restorative justice conference.

- At the Conference, the young person reads the apology letter aloud, and the victim(s) describes their experience and the harms caused by the offense. The youth responds to the victim(s) and answers questions posed by other conference participants. After other participants offer their perspectives, everyone present works together to craft a restorative plan for the youth to repair the harm caused by the offense, and to identify and secure whatever support the young person needs to succeed and avoid repeating the problematic behaviors.

- In the Plan Completion Stage, program staff outline steps the youth will follow to complete the plan, to ensure that the youth has ongoing support from family and other supporters, and to identify any resources and additional assistance that might be needed. Staff follow up with the youth as necessary, and then convene a closing meeting with the youth and their family and supporters to celebrate the conclusion of the process.

Impact Justice identifies eight core elements that underlie its model: (1) oriented around the person harmed; (2) focused on ending disparities by targeting offenses where arrests disproportionately involve youth of color; (3) structured as a diversion with no formal charges in court; (4) limited to youth whose offenses are serious and would otherwise be charged in court; (5) strengths-based, meaning it is aimed at helping build on young people’s strengths, not fixing what’s wrong with them; (6) rooted in relationships; (7) confidential, so that nothing said in the conference process can be used against youth in court; and (8) community-based, so that the process is overseen by community organizations, rather than the court.104

Evidence of effectiveness: While the research is not entirely consistent, most studies find that restorative justice approaches lead to lower reoffending rates than traditional prosecution in court. For instance, a 2016 meta-analysis of restorative conferencing programs for youth and adults found that these programs lead to “a modest but highly cost-effective reduction in repeat offending.”105 A review of restorative justice research conducted by the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Justice found that restorative justice led to significantly lower reconviction rates than standard court processing.106

Two recent studies found that restorative justice conferencing programs for youth accused of serious offenses reduced recidivism. A 2017 evaluation of a program operated by Community Works West in Alameda County (Oakland), Calif., found that youth who were diverted from court and participated in restorative conferencing were 47% less likely to be found delinquent within 18 months than a randomly assigned control group who were prosecuted in juvenile court. This program worked with youth accused of serious crimes (62% were accused of felonies) that caused harm to an identifiable victim. More than 90% of victims reported satisfaction with the restorative conferencing process, saying they would participate again and recommend it to a friend, as did the vast majority of participating youth and their parents.107 A 2021 study of the “Make it Right” restorative conferencing diversion project in San Francisco, which worked with 13- to 17-year-olds accused of felonies such as burglary and assault, found that restorative justice conferencing reduced participants’ rearrest rate by 33% in the year after enrollment, compared to peers in a randomly assigned control group who were prosecuted in court.108

Status of and support for replication efforts: Through its national Restorative Justice Project, Impact Justice provides extensive training and assistance to a network of 11 restorative justice diversion programs nationwide as of March 2023.109 For these sites, and for any other jurisdictions interested in creating new restorative justice diversion programs for youth accused of serious offenses, Impact Justice provides a series of introductory online webinars110 and an online toolkit.111 Finally, Impact Justice offers both live and virtual training and access to national and regional meetings, as well as opportunities for stakeholders (community-based organizations, court and probation officials, funders, and others) to exchange ideas with peers across jurisdictions.112

FIGURE 4. Diverting Youth to Restorative Justice Works — Even for Serious Offenses

Restorative Community Conferencing (RCC) Program cuts recidivism in Alameda County, CA.

Wraparound Care

Overview: Wraparound programs offer coordinated care for children and adolescents diagnosed with serious emotional disturbances who might otherwise require placement in residential facilities. Though wraparound programs have become increasingly widespread over the past two decades, wraparound’s use for youth facing serious delinquency charges, and who might otherwise be incarcerated, remains limited. However, some jurisdictions do use wraparound widely for youth involved with delinquency courts, and several studies show that these programs can lower offending rates and vastly reduce the use of correctional confinement or other out-of-home placements.

Core elements and variations on the model: Wraparound programs provide integrated and coordinated care for youth with serious emotional disturbances who are at risk of being removed from their homes. The programs are characterized by two core features: (1) they are supported by blended funding arrangements, known as “systems of care,” that combine funds from a variety of public systems (e.g., Medicaid, child welfare, juvenile justice, adolescent mental health, education, and more) to create a vast menu of treatment services and other supports; and (2) they are overseen by care coordinators who work with families to assess needs, create individualized plans tailored to the needs of each young person, and connect children and their families to needed services.113 As the U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention has described it, this process “involves ‘wrapping’ a comprehensive array of individualized services and support networks ‘around’ young people in the community, rather than forcing them to enroll in predetermined, inflexible treatment programs.”114

In Wisconsin, Wraparound Milwaukee operates a robust program serving more than 1,000 children and adolescents each year, many of whom are involved in the justice system. On an average day in 2014, Wraparound Milwaukee served 425 youth involved in the youth justice system.115 Wraparound Milwaukee had a total budget in 2020 of $43 million from multiple funding streams; it used those funds to contract with a vast provider network, covering everything from mental health and substance abuse treatment, to camps and afterschool programs, to emergency food and clothing and housing assistance.116 Wraparound Milwaukee also funds local social services organizations to provide care coordinators who create a child and family team for every young person they serve, and then work with those teams to create individualized service plans and connect youth to relevant services and opportunities.

Evidence of effectiveness: One study found that a wraparound care program in Clark County, WA, reduced participants’ recidivism rates by a third, both for felonies and for all offenses, relative to comparable youth whose cases occurred before the program began.117 A study in Alabama found that the likelihood of subsequent juvenile justice system involvement fell sharply for court-involved youth served by a wraparound program in Birmingham, but rose slightly for comparable youth in Montgomery who received usual treatment (not wraparound services) in the juvenile court and mental health systems.118 In the Wraparound Milwaukee program, participants have shown substantial improvements in mental health and school attendance, and fewer placements into foster care or residential treatment programs.119 As regards reoffending, just 14% of court-involved youth participating in Wraparound Milwaukee from 2012-2014 were rearrested, far lower than the 41% rearrest rate for the youth on juvenile probation who did not participate in wraparound.120

Status of and support for replication efforts: In addition to Milwaukee, wraparound programs specifically targeting youth in the juvenile justice system operate in Georgia121 and in several Illinois counties,122 among other jurisdictions. In 2013, the federal government’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration issued a guidance document formally endorsing states’ use of the wraparound approach to caring for children and youth with serious emotional disturbances,123 thus helping to accelerate a rapid expansion of wraparound programs throughout the US.124 A National Wraparound Initiative supports wraparound replication efforts, providing training and workforce development, technical assistance, and evaluation assistance.125

Homegrown Alternatives

While the six models described above offer solid evidence of effectiveness and strong readiness for replication, they are not the only – or necessarily the best – approaches for every jurisdiction. Indeed, considerable research finds that homegrown programs which do not follow the specific protocols of any pre-established model may produce equal or better outcomes.126

Therefore, in considering which alternative-to-incarceration programming to develop in their jurisdictions, local justice system leaders should convene a stakeholder group to examine the resources available in their communities, brainstorm possible approaches to providing home-based care and supervision for youth at high risk for incarceration, and weigh the merits of homegrown options against the six existing models highlighted in this report.

If they choose to develop a homegrown program, local leaders should recognize that the first key to success lies in heeding the evidence of what works by creating a model that combines several key elements.

- Limit participation to youth at high risk for reoffense who might otherwise be incarcerated.

- Work closely with families to craft and follow individualized plans tailored to the interests, needs, and circumstances of the youth being served.

- Include intensive mentoring, ideally with credible messengers who come from similar backgrounds and reside in neighborhoods where many court-involved youth live.

- Offer evidence-based cognitive behavioral therapy to help youth develop thinking skills necessary to avoid further delinquency.

- Connect youth with employment or other positive youth development activities, plus any needed mental health care, substance abuse treatment, family counseling, and other indicated services.

Finally, in order to succeed, alternative-to-incarceration programs must have strong leadership, and they must hire and adequately train highly motivated staff.

Complementary System Reforms to Minimize Incarceration

Effective alternative-to-incarceration programs are essential for youth justice systems to reduce overreliance on incarceration. However, such programs are only part of the answer. Even the best-designed interventions will yield little benefit if they operate within dysfunctional justice systems that ignore important evidence and are prone to making bad decisions rooted in a punitive rather than rehabilitative mindset.

As The Sentencing Project will explore in a forthcoming companion report, this is true for two reasons. First, problematic policies and practices at the system level can undermine the effectiveness of even the best alternative-to-incarceration program models. To make a measurable difference, alternative programs must be reserved for youth with serious offending histories who pose an immediate risk to public safety. If instead courts use these rigorous alternative programs for youth who pose lesser risk, their impact on incarceration rates will be far lower. In fact, they may even worsen young people’s outcomes.

A consistent lesson of youth justice research, known as the “risk principle,” finds that interventions work best when the intensity of service is matched to the risk level of the young person: whereas higher-risk youth achieve better outcomes with intensive supports and services, youth with limited offending histories actually do better when they receive minimal interventions.127 To maximize the success of alternative-to-incarceration programs, youth justice systems must also implement the programs carefully, adhering to the essential core elements of the models and ensuring that staff are well-qualified, highly motivated, well-trained, and adequately paid.128

Second, youth incarceration rates will remain too high unless state and local justice systems break their continuing harmful practice of incarcerating youth who pose minimal risks to public safety. Specifically, reforms are required in the following areas:

- Youth justice systems must adopt policies and practices that steer youth away from further involvement in the justice system as often as possible at every stage of the court process, particularly by reducing arrests,129 expanding the share of youth diverted from formal court processing,130 and minimizing the use of pre-trial detention.131

- Juvenile courts and probation agencies must work closely with families and community organizations to explore all available options to keep young people home – only placing youth into institutions as a last resort for those who pose an immediate threat to public safety.

- States must incentivize the use of effective alternative-to-incarceration program models.132

- States and localities must ensure access to rigorous treatment to prevent incarceration of youth who have mental illnesses.133

- Youth justice systems must shift the focus of juvenile probation away from monitoring compliance with court rules and toward helping young people grow out of problematic behaviors.134

- Courts must abandon the practice of incarcerating youth solely for probation-rule violations.135

At the same time, state and local youth justice systems must make concerted, determined efforts to reduce the longstanding biases that have perpetuated the glaring racial and ethnic disparities in confinement that remain the youth justice system’s most prominent and troubling characteristic.

Conclusion

Leaders of youth justice systems nationwide, as well as legislators who enact the laws and approve their budgets, must heed the compelling evidence showing that incarceration is a failed strategy for reversing delinquent behavior. They must recognize that incarceration should be imposed only on young people who present a serious immediate threat to other people’s safety, and they must fund and deliver effective alternative-to-incarceration programs to keep many of the youth who are currently being incarcerated at home, safely.

In the end, the most essential ingredient for reducing overreliance on youth incarceration is the determination to explore every option to keep young people at home safely, providing youth with the support and assistance they require to avoid further offending, participate in the age-appropriate rites of adolescence, and mature toward a healthy adulthood.

| 1. | The second challenge, addressing the need for system reforms, will be the focus of a companion report by The Sentencing Project, to be released in the summer of 2023. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Information about the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative is available on the Foundation’s website, at https://www.aecf.org/work/juvenile-justice/jdai. |

| 3. | Feld, B. (1999). Bad Kids: Race and the Transformation of the Juvenile Court (pp. 280). Oxford University Press. |

| 4. | Mendel, R. (2011). No Place for Kids: The Case For Reducing Juvenile Incarceration. Annie E. Casey Foundation; Mendel, R. (2023). Why youth incarceration fails: An Updated Review of the Evidence. The Sentencing Project. |

| 5. | Mendel (2011 & 2023), see note 4. |

| 6. | Mendel (2011 & 2023), see note 4. |

| 7. | Mendel (2023), see note 4; Mendel, R. (2014). Juvenile detention alternatives initiative progress report. Annie E. Casey Foundation. |

| 8. | Mendel (2023), see note 4. |

| 9. | Mendel (2023), see note 4. |

| 10. | Mendel, R. (2015). Maltreatment in U.S. juvenile correctional facilities. Annie E. Casey Foundation. |

| 11. | Mendel (2023), see note 4. |

| 12. | Rovner, J. (2021). Black disparities in youth incarceration. The Sentencing Project. |

| 13. | Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2022). Increase successful diversion for youth of color; Spinney, E., Cohen, M., Feyerherm, W., Stephenson, R., Yeide, M., & Shreve, T. (2018). Disproportionate minority contact in the US juvenile justice system: a review of the DMC literature, 2001–2014, part I. Journal of Crime and Justice, 41(5), 573-595. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.2018.1516155; Rodriguez, N. (2010). The cumulative effect of race and ethnicity in juvenile court outcomes and why pre adjudication detention matters. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 47(3), 391-413. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427810365905 |

| 14. | Puzzanchera, C., & Hockenberry, S. (2022). Patterns of juvenile court referrals of youth born in 2000. Juvenile Justice Statistics: National Report Series Bulletin; Steinberg, L. (2009). Adolescent development and juvenile justice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5, 459-85. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153603 |

| 15. | Mulvey, E. (2011). Highlights from pathways to desistance: A longitudinal study of serious adolescent offenders. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention |

| 16. | Steinberg, L. D., Cauffman, E., & Monahan, K. (2015). Psychosocial maturity and desistance from crime in a sample of serious juvenile offenders. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. |

| 17. | Schaefer, S. & Erickson,G. (2019) Context matters: juvenile correctional confinement and psychosocial development. Journal of Criminal Psychology, Vol. 9 Issue: 1, pp. 44-59. Dmitrieva, J., Monahan, K.C., Cauffman, E. & Steinberg, L. (2012). Arrested development: The effects of incarceration on the development of psychosocial maturity. Development and Psychopathology 24(3), 1073–1090. |

| 18. | Baglivio, M. T., Epps, N., Swartz, K., Huq, M. S., Sheer, A., & Hardt, N. S. (2014). The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) in the lives of juvenile offenders. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 3(2). |

| 19. | Baglivio et al. (2014), see note 18. |

| 20. | Crosby, S. D. (2016). Trauma-informed approaches to juvenile justice: A critical race perspective. Juvenile and Family Court Journal, 67(1), 5-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfcj.12052 |

| 21. | National Research Council. (2013). Reforming juvenile justice: A developmental approach. National Academies Press. |

| 22. | National Research Council (2013), see note 21. |

| 23. | National Research Council (2013), see note 21. |

| 24. | Mendel (2023), see note 4. |

| 25. | Lipsey, M., Landenberger, N., & Wilson, S. (2007), Effects of cognitive-behavioral programs for criminal offenders. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 3, 1-27. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2007.6 |

| 26. | Raposa, E., Rhodes, J., Stams, G., et al. (2019). The effects of youth mentoring programs: A Meta-analysis of outcome studies. J Youth Adolescence, 48, 423–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-00982-8; Christensen, K. M., Hagler, M. A., Stams, G. J., Raposa, E. B., Burton, S., & Rhodes, J. E. (2020). Non-specific versus targeted approaches to youth mentoring: A follow-up meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49, 959-972. |

| 27. | Lynch, M., Astone, NM., Collazos, J., Lipman, M., & Esthappan, S. (2018). Arches transformative mentoring program. Urban Institute; Cramer, L., Lynch, M., Lipman, M., Yu, L., & Astone, N. M. (2018). Evaluation report on New York City’s advocate, intervene, mentor program. Urban Institute. |

| 28. | Fagan, A. (2013). Family-focused interventions to prevent juvenile delinquency: A case where science and policy can find common ground. Criminology & Public Policy, 12, 617–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12029. Henggeler, S. (2015). See note 28. |

| 29. | Henggeler (2015), see note 28. |

| 30. | Barton, W., & Butts, J. (2008). Building on strength: Positive youth development in juvenile justice programs. Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago; Butts, J., Bazemore, G., & Meroe, A. (2010). Positive youth justice–framing justice interventions using the concepts of positive youth development. Coalition for Juvenile Justice. |

| 31. | Development Services Group. (2014). Positive youth development literature review. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. |

| 32. | Durlak, J., & Weissberg, R., & Pachan, M. (2010). A meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45, 294-309. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2007.6; Development Services Group. (2014). Positive youth development literature review. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. |

| 33. | Katsiyannis, A., Ryan, J., Zhang, D., & Spann, A. (2008) Juvenile delinquency and recidivism: The impact of academic achievement. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 24(2), 177-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560701808460; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Education and delinquency: Summary of a workshop. (2000). The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9972 |

| 34. | Guryan, et al. (2021). Not too late: Improving sentencing outcomes among adolescents. National Bureau of Economic Research; The Education Trust & MDRC staff. (2021). Targeted intensive tutoring as a strategy to solve unfinished learning. The Education Trust. |

| 35. | Norrbin et al (2004). Using civil representation to reduce delinquency among troubled youth. Evaluation Review, 28(3), 201-217. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X03262587 |

| 36. | Butts et al. (2010), see note 30. |

| 37. | Butts et al. (2010), see note 30. |

| 38. | Butts et al. (2010), see note #30. Young, S., Greer, B., & Church, R. (2017). Juvenile delinquency, welfare, justice and therapeutic interventions: a global perspective. BJPsych bulletin, 41(1), 21-29. |