Incarceration and Crime: A Weak Relationship

Nearly 50 U.S. states have reduced both incarceration rates and crime in the last decade. We don’t have to return to a punitive playbook in the face of recent crime upticks.

Related to: Incarceration

Pandemic-Era Crime Upticks Test Commitment to Evidence-Based Policies

A decade after national protests catapulted the Black Lives Matter movement following the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri and four years after a national racial reckoning triggered by Minneapolis police officers killing George Floyd, lawmakers are wavering on their commitment to making the criminal legal system more just and effective.1 Many are reverting to the failed playbook of the 1990s which, as this brief will show, dramatically increased incarceration, particularly among Black Americans, with limited benefits to community safety. The recent move away from evidence-based policymaking includes New York’s reversal of its bail reform law, Louisiana’s expansion of its already draconian prison sentences, and Oregon’s repeal of Measure 110, which had decriminalized the possession of controlled substances in favor of a public health response.2

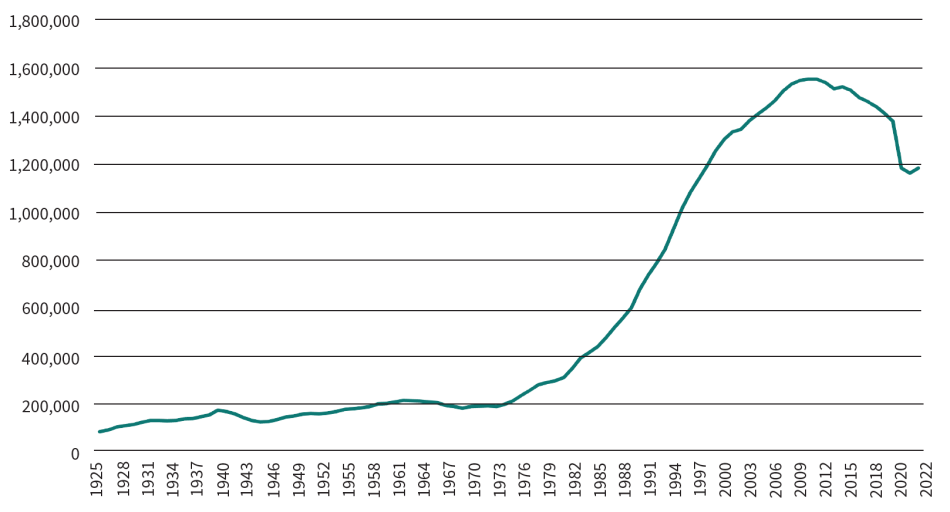

This shift threatens the modest progress made in recent years in reducing U.S. incarceration levels. The United States now ranks sixth globally in its incarceration rate – as much as eight times the rate of industrialized peer countries.3 Following a nearly 700% buildup in imprisonment since 1972, the U.S. prison population downsized by 25% between 2009 and 2021 – falling to under 1.2 million people.4 A significant portion of this decline occurred in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, when reduced prison admissions and expedited releases downsized the prison population by 14%.5 Interventions such as the transfer of approximately 11,000 people from federal prisons to home confinement demonstrated that in some cases, substantial decarceration could accompany extremely low recidivism rates.6 Nevertheless, imprisonment levels increased in 2022.7

Figure 1. State and Federal Prison Population, 1925-2022

Sources: Bureau of Justice Statistics. (1982). Prisoners 1925-81; Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2024, April 2). Sentenced prisoners under the jurisdiction of state or federal correctional authorities, December 31, 1978-2019. Corrections Statistical Analysis Tool (CSAT) – Prisoners. https://csat.bjs.ojp.gov/quick-tables; Carson, E. A., & Kluckow, R. (2023). Prisoners in 2022 – Statistical tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics.

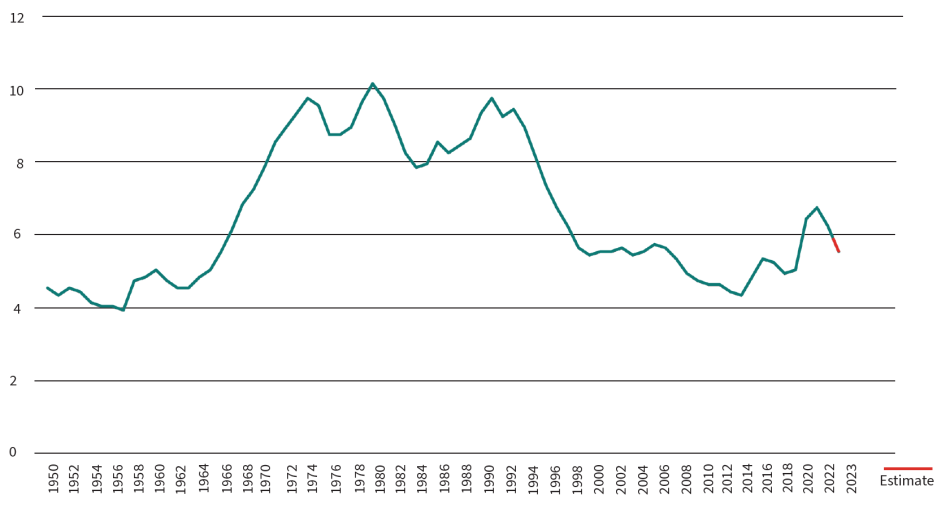

Rates of crimes reported to U.S. law enforcement reached peak levels in the 1990s, and fell roughly 50% by year end 2019.8 However, the uptick in the 2022 prison population – following eight years of modest decline – occurred in the midst of growing concern about crime. The economic, social, and psychological turbulence of the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to a seismic shift for the most serious crime: homicide. Homicides spiked up 27% in 2020 and remained at elevated rates until declining substantially in 2023.9 Reported rates of violent and property crime exhibited typical fluctuations amidst the pandemic, although household surveys of violent victimization showed a more dramatic increase across the country.10 Motor vehicle thefts, which were at near-historic lows by 2019, also increased in the subsequent years, as did carjackings.11 These facts, combined with bouts of misleading media coverage have heightened public concern about crime.12 When combined with a growing sense of disorder and the persistence of the drug/opioid overdose crisis, the result has been eroded policy debates about how to create community safety.

Figure 2. U.S. Homicide Rate per 100,000 Residents

Sources: Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2024, April 2). Crime data explorer. https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend; Cooper, A. D., & Smith, E. L. (2011). Homicide trends in the United States, 1980-2008. Bureau of Justice Statistics; Asher, J. (2024, April 2). It’s early, but murder is falling even faster so far in 2024. Jeff-alytics

The growing punitive shift threatens to reverse the success of recent decarceration and erode the “generational shift” that scholars have identified in reducing the lifetime likelihood of imprisonment for Black men – which still remains far above their white counterparts.15 Instead of reverting to a failed political playbook, policymakers must effectively respond to the recent uptick in lethal violence, the overdose crisis, and concerns about unhoused populations through evidence-based responses.16 In tandem, they must correct the counterproductive, costly, and cruel response of mass incarceration.

Lessons From the Historic Crime Drop

Understanding mass incarceration’s limited contribution to the historic crime drop, which began in the 1990s, strengthens the case for pursuing substantial decarceration. Rates of crime reported to the police in the United States grew dramatically beginning in the 1960s, reached their peak in the early 1990s, and then plummeted over the subsequent two and a half decades.24 The reported violent crime rate, for example, peaked at 758 per 100,000 residents in 1991 and fell to a low of 362 per 100,000 in 2014 – a 52% drop.8 In 2022, the most recent year for which national data are available, the reported violent crime rate was 381 per 100,000 – still 50% lower than its peak rate in 1991.13 Several studies have established that the increased confinement of people in prisons, from about nearly 200,000 in 1972 to a peak of nearly 1.6 million in 2009, accounted only modestly for this crime drop.27

Over two dozen countries experienced crime waves and drops comparable to that of the United States but most did not expand imprisonment anywhere close to the scale of the United States.28 In contrast, incarceration levels in the United States exploded, quadrupling the prison population between 1972 and 1991, the period of the crime wave. Imprisonment levels then doubled again between 1991 and 2009, while crime rates were falling.29 The prison population finally began its modest decline in 2010, entering a nearly decade-long period when both crime and incarceration levels declined in unison.30

Scholars examining state imprisonment trends during the period of extreme growth conclude that incarceration contributed only modestly to the crime drop. They find that in the 1990s mass incarceration accounted for as much as 35% or as little as 6% of the crime drop.31 These estimates depend on the type of crime under investigation as well as the methodology and assumptions used by analysts. Since the turn of the century, mass incarceration appears to have made almost no contribution to the crime drop.32 Reviewing the four-decade period when incarceration levels increased without any consistent relationship with crime rates, the National Research Council has concluded that “the increase in incarceration may have caused a decrease in crime, but the magnitude of the reduction is highly uncertain and the results of most studies suggest it was unlikely to have been large.”33

Some of the reasons that mass incarceration has contributed so little to community safety are:

- The War on Drugs has failed to mitigate the harms of drug use by incarcerating drug sellers who are easily replaced, and by failing to treat substance use disorders, while diverting resources from more effective interventions;34

- Incarceration often fails to offer adequate rehabilitative services that can address factors such as economic disadvantage and/or trauma that contribute to crime, and sometimes exacerbates these problems through the experience of incarceration and its associated collateral consequences;35 and

- Increasing sentence lengths does not deter crime, and thus does not promote community safety as shown by an abundance of criminological research.36

Why Longer Sentences Don’t Work

A key part of mass incarceration has been the rise of lengthy sentences. More Americans are serving life sentences today than the total prison population in 1970.37 In addition, 19% of the prison population has already served at least 10 years.38 Yet, research has shown that lengthy prison terms often incarcerate people long after they have aged out of crime:39

- Recidivism rates drop dramatically among people who have served longer than six to 10 years compared to those who have served shorter sentences.40

- “Criminal careers” typically end within approximately 10 years.41

- Research on the age-crime curve, which measures the proportion of individuals in various age groups who engage in crime based on arrest trends, shows that for a range of offenses, including robbery and murder, criminal offending peaks around the late teenage years or early 20s, then begins a gradual decline in the early 20s.42

Longer sentences also fail to deter others from criminal activity. As Daniel Nagin, professor of public policy and statistics at Carnegie Mellon University and a leading national expert on deterrence, writes: “Increases in already long prison sentences, say from 20 years to life, do not have material deterrent effects on crime.”43 Long sentences are limited in deterring future crimes because most people do not expect to be apprehended for a crime, are not familiar with relevant legal penalties, or commit crime with their judgment compromised by substance use or mental health problems.44

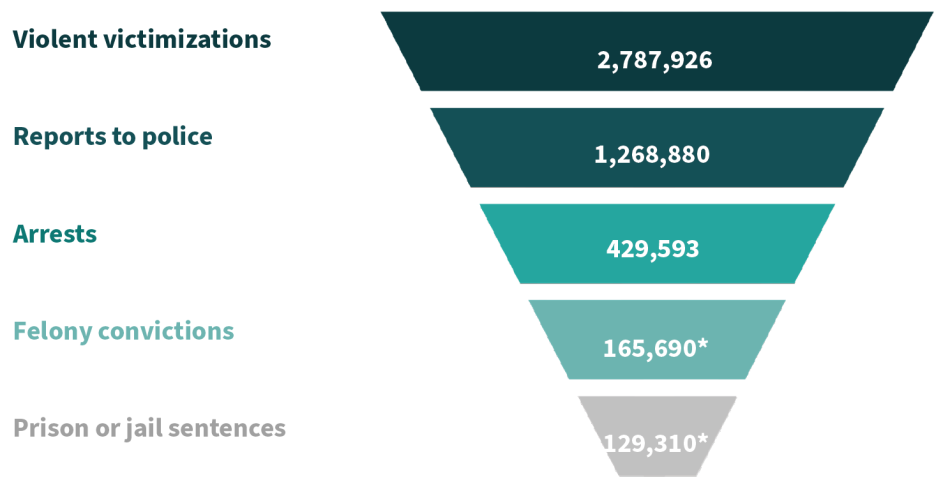

Another way to understand mass incarceration’s limited contribution to the crime drop is by visualizing the system itself as a funnel. We illustrate the funnel model using the violent crimes of aggravated assault, robbery, rape, and murder/nonnegligent homicide. According to the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), a nationally representative snapshot of victimization experiences across the United States, in 2022 the number of violent victimizations surpassed 2.7 million yet fewer than half were reported to police.45 While reporting rates vary by crime type, individuals choose not to report for a variety of reasons including handling it informally, thinking it was not serious enough to report, or not believing that law enforcement could or would do anything.46 Of violent offenses reported, roughly one-third resulted in an arrest.47 For a variety of factors, as cases exit or proceed through the criminal legal system, a fraction of those arrested – roughly 130,000 people – are sentenced to a term of incarceration.48 In other words, the criminal legal system addresses a small proportion of crimes that impact the safety of our communities.

Figure 5. The Criminal Legal Funnel and Violent Crime

Note: Violent crime types depicted include aggravated assault, robbery, rape, and murder/nonnegligent homicide. Because the NCVS does not measure homicide victimizations, the UCR murder/nonnegligent manslaughter count is added to the violent victimizations count. Violent victimizations, reports to police, and arrests use 2022 data, the most recent year available.

* Felony convictions and related incarceration for the above-listed crimes use 2006 data, the most recent year available, and pertain to state courts. In 2006, there were 2,355,704 violent victimizations, 1,417,745 violent crimes reported to police, and 611,523 arrests.49

Sources: FBI crime data explorer. Crime in the United States annual report, 2022: CIUS estimates “Crime in the United States (CIUS), Table 1” & persons arrested “Estimated number of arrests, Table 29.” FBI Uniform Crime Reporting Program; Rosenmerkel, S., Durose, M., & Farole Jr., D. (2010). Felony sentences in state courts, 2006 – Statistical tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics; Thompson, A., & Tapp, S. N. (2023). Criminal victimization, 2022. Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Researchers have identified many factors, other than incarceration, that contributed incrementally to the U.S. crime drop. These include the decline of the crack cocaine market, a decline in the share of the population that falls into high-risk age groups, and the growing immigrant population who have lower crime rates than native-born Americans – and there is ongoing debate about the magnitude of impact from factors such as improvements in the economy and changes in policing.50

Lessons From the Recent Era of State and Federal Decarceration

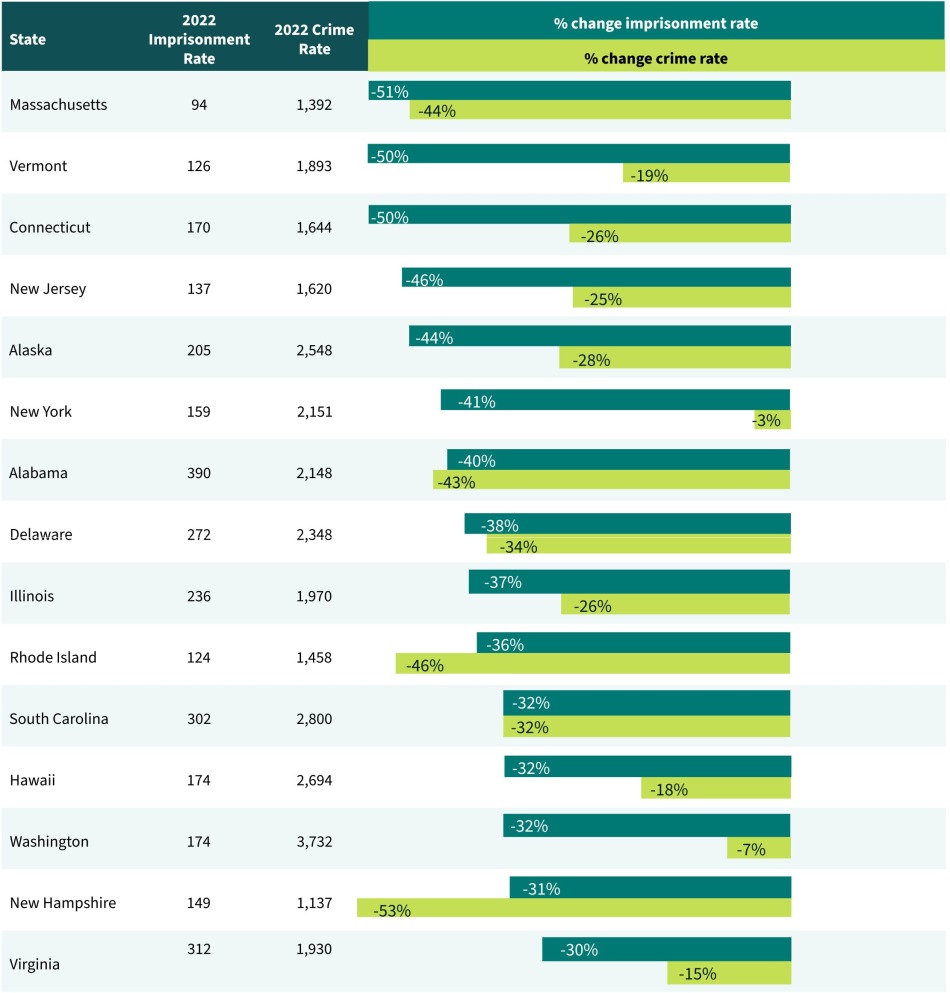

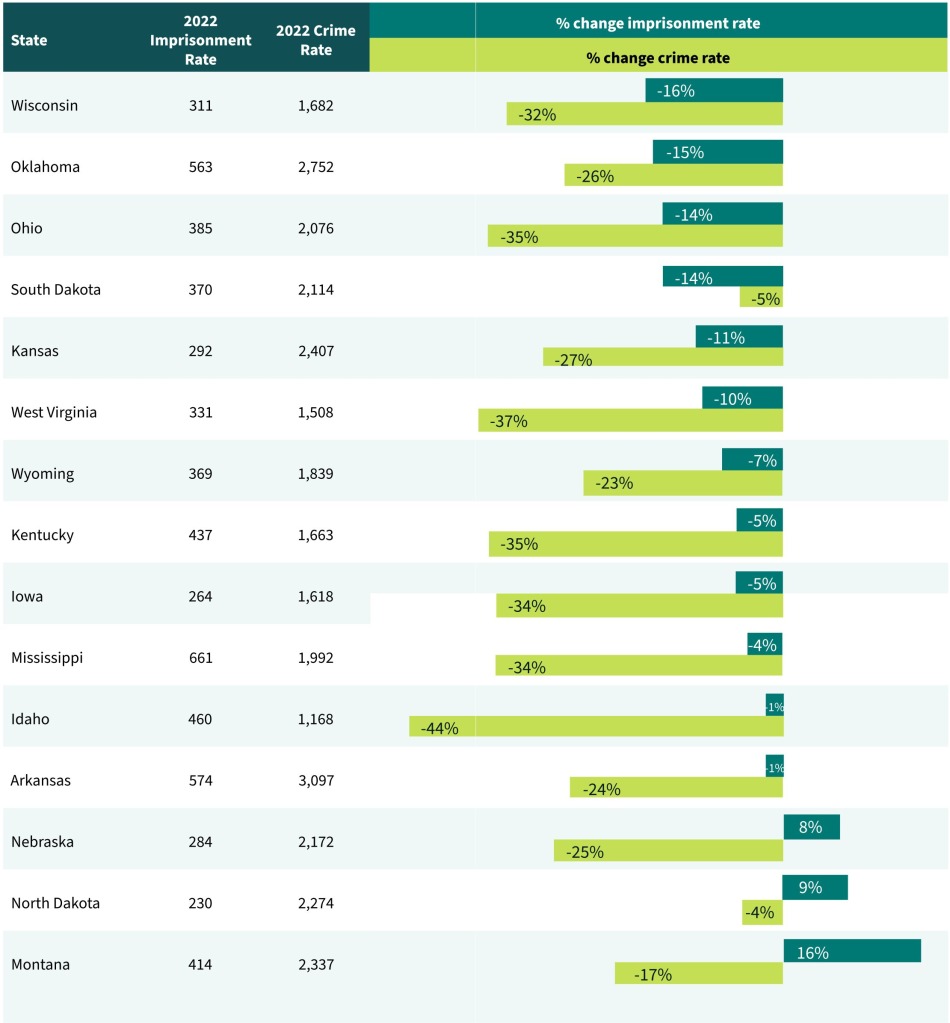

As some lawmakers pivot to widen the reach of the criminal legal system in response to public concern, recent state trends illustrate that less imprisonment often happens alongside improvements to community safety. Over a nine year period (2013-2022), 46 states reduced the footprint of their prison population while experiencing crime declines. In some states, these declines were substantial.51

Figure 6. State Imprisonment and Crime Trends, 2013-2022

Notes: Crime figures reflect violent and property crimes for Part I offenses as defined in the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports (UCR). Crime and imprisonment rates are per 100,000 U.S. residents. All years use the UCR’s revised definition of rape. This analysis updates The Pew Charitable Trusts’ work: Pew. (2014). Most states cut imprisonment and crime.

Sources: Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime in the United States by state, 2013 (Table 5). U.S. Department of Justice; FBI crime data explorer. Crime in the United States annual report, 2022: CIUS estimates “Crime in the United States by state, 2022” (Table 5). FBI Uniform Crime Reporting Program; Carson, E. A. (2014). Prisoners in 2013 (Table 6). Bureau of Justice Statistics; Carson, E. A. (2015). Prisoners in 2014 (Table 6). Bureau of Justice Statistics; Carson, E. A., & Kluckow, R. (2023). Prisoners in 2022 (Table 7). Bureau of Justice Statistics.

But experiencing declines in crime and incarceration has not prevented some states from returning to a punitive playbook in the face of crime upticks. Louisiana, for example, reduced its prison population by 30% while experiencing an 18% decrease in its crime rate from 2013 to 2022. While some Louisiana cities in 2022 and 2023 saw sharp increases in homicides, preliminary data suggests many of these trends are reversing. For example, preliminary 2024 data from New Orleans suggest that most violent crime, including homicide, is trending down.52 Yet, in response to these temporary spikes in violent crime, Louisiana lawmakers increased sentences for certain crime types in a special session in 2024, requiring 85% of sentences to be served prior to possible release for “good time” credit, eliminating parole with very few exceptions, and automatically sending 17-year-olds to adult criminal court.53 Instead of investing in evidence-based, localized responses to crime, particularly in communities experiencing sharp increases in violence, lawmakers took a broad state-wide approach which is anticipated to balloon the state’s prison and jail populations, while contributing little to community safety.54

Utah made a similar pivot in 2024 to more punitive laws, from creating new offenses to increasing sentences.55 This is in contrast to Utah’s nine-year trend. From 2013 to 2022, Utah’s prison population fell almost 30% in tandem with a nearly 33% decrease in the crime rate. Rather than meaningfully grapple with the uptick in crime, these policies will contribute to mass incarceration’s continuation.

Federal-level research also shows that decarceration does not negatively affect community safety. A series of analyses conducted by the United States Sentencing Commission assessed sentencing reductions for individuals convicted of crack cocaine trafficking, manufacturing, or possession. The Commission examined whether “offenders who received a reduced sentence retroactively were more likely to recidivate than similarly situated offenders who did not receive a reduced sentence.”56 With follow-up periods ranging from three to five years after release from incarceration, this analyses showed that individuals released early did not have higher recidivism rates compared to those who served their full sentence.57

A Future Without Mass Incarceration: Embracing Evidence-Based Policies

Policymakers’ responses to fluctuations and spikes in crime – including during periods of intense social instability and recovery (e.g., recessions, COVID-19) – must move beyond a reactionary, excessively punitive playbook. Incarcerating more people, and lengthening prison sentences, does not address the underlying safety needs of communities. Reforms should be grounded in the accumulation of knowledge about incarceration as well as evidence-based strategies to improve communities and their well-being. While research indicates that incarceration does have some impact on crime, non-prison approaches to community safety should be prioritized as supported by research. In the absence of legislative reforms, legal actors, especially prosecutors, should use their discretion to achieve these objectives.58

Our recommendations include:

- Reduce unnecessary justice involvement. State and federal lawmakers should shift from criminalizing people who use drugs toward public health solutions that expand treatment and also its affordability (e.g., universal health care coverage).59 Improving access to harm reduction services, including safe community settings to prevent overdoses (i.e., supervised consumption sites), can reduce other negative outcomes of drug use.60 In addition, criminal legal offices in jurisdictions, such as local courts, probation departments and prosecutor’s offices, should collaborate with each other to expand access to diversion programs as alternatives to prosecution and incarceration. Moreover, more youth should be diverted from the juvenile court system. Evidence shows, compared to youth prosecuted in the juvenile system, most diverted youth have far better education and employment outcomes and far less subsequent justice system involvement.61 Local jurisdictions should also be well-resourced to invest in violence intervention programs that leverage public health concepts that interrupt conflicts, work to change social norms around the use of violence in response to conflict, and act as a bridge to community services as well as work and educational opportunities.62

- Leverage non-carceral responses to crime. Invest in other forms of accountability, such as community supervision, to minimize short stints of incarceration, given that a number of studies have found that community supervision produces better public safety outcomes than shorter terms of imprisonment.63 Because the expansion of community supervision can increase the likelihood of incarceration,64 such supervision should be used sparingly and be of minimal duration. This way it does not act as a “trip wire” to incarceration and supports maintaining prosocial behaviors like employment.65 For youth, invest in alternative-to-incarceration programs as well as policy and practice reforms to limit unnecessary and counterproductive use of incarceration for individuals who do not pose serious threats to public safety.66

- Eliminate lengthy and extreme sentences. Limit prison terms beyond 10 years and cap them at 20 years with limited exceptions.67 Criminological evidence shows that criminal careers typically end within approximately 10 years68 and recidivism rates fall measurably after about a decade of imprisonment.40 Since racial disparities increase with sentence length, this reform would also help to reduce racial disparities in incarceration, as noted by the National Research Council.70 Also eliminate mandatory minimum sentences, given that they prolong sentences and contribute to racial disparities.71

- Permit a “second look” at lengthy and extreme sentences. The American Bar Association’s policymaking body, the House of Delegates, urges lawmakers to authorize courts to take a “second look” at criminal sentences after 10 years of imprisonment.72 The American Law Institute recommends that all prison sentences be reviewed within 10 years for youth convictions, and after 15 years for crimes by adults, so that sentences reflect our “evolving norms…and knowledge base.”73

- Eliminate bias. Ensure that future laws do not succumb to biases, such as through the use of racial impact statements.74 Analogous to fiscal impact statements, racial impact statements are a tool for lawmakers to evaluate potential disparities of proposed legislation prior to their adoption and implementation. Nine states – Iowa, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Oregon, Maine, Maryland, New Jersey, and Virginia – have implemented mechanisms for creating racial impact statements; in addition, the Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission creates racial impact statements and Washington, DC, officials established an equity impact statement policy.75 To monitor the efficacy of laws and policies with impact statements, jurisdictions should allocate resources for consistent data collection, analysis, and transparency of findings to identify and correct any biases that may still result. And as Nicole D. Porter of The Sentencing Project has testified: “To undo the racial and ethnic disparity resulting from decades of punitive policies … states should also repeal existing racially biased laws and policies.”76

| 1. | Lartey, J. (2024, March 9). These states are once again embracing ‘Tough-on-Crime’ laws. The Marshall Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | McKinley, J., Ashford, G., & Meko, H. (2023, April 28). New York will toughen contentious bail law to give judges more discretion. The New York Times; Lartey, J. (2024, March 9). These states are once again embracing ‘Tough-on-Crime’ laws. The Marshall Project; Crombie, N. (2024, April 1). Gov. Tina Kotek signs new law making drug possession a crime again, says ‘business as usual’ cannot continue. The Oregonian. |

| 3. | The U.S. incarceration rate of 531 per 100,000 residents compares to a rate of 67 in Germany, 109 in France, and 146 in England and Wales. World Prison Brief. (2024, April 2). Highest to lowest – Prison population rate. https://www.prisonstudies.org/highest-to-lowest/prison_population_rate. |

| 4. | Carson, E. A., & Kluckow, R. (2023). Prisoners in 2022 – Statistical tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics; Bureau of Justice Statistics. (1982). Prisoners 1925-81. |

| 5. | Carson, E. A., & Kluckow, R. (2023). Prisoners in 2022 – Statistical tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 6. | Gwinn, J. (2024). CARES Act: Analysis of recidivism. Federal Bureau of Prisons; Gill, M. (2022, September 29). Thousands were released from prison during covid. The results are shocking. The Washington Post. |

| 7. | Carson, E. A., & Kluckow, R. (2023). Prisoners in 2022 – Statistical tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 8. | Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2024, April 2). Crime data explorer. https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend. |

| 9. | Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2024, April 2). Crime data explorer. https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend |

| 10. | The reported violent crime rate climbed slightly in 2020, then resumed its decline. The reported property crime rate continued its decline in the early part of the pandemic but then bumped up in 2022. The National Crime Victimization Survey – which measures both reported and unreported crimes – found dramatic increases in several violent crime categories in 2022. Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2024, April 2). Crime data explorer. https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend; Rosenfeld, R., & Lauritsen, J. (2023). Did violent crime go up or down last year? Yes, it did. Council on Criminal Justice; Johnson, T., Johnson, N., & Sabol, W. (2024, March 13). America’s suburban crime problem. Time. Asher, J. (2024, April 8). The UCR vs NCVS conundrum. Jeff-alytics. |

| 11. | Car thefts were driven in part by technological inadequacies of Hyundais and Kias. Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2024, April 2). Crime data explorer. https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend; Lopez, E., & Boxerman, B. (2024). Crime trends in U.S. cities: Year-end 2023 update. Council on Criminal Justice; Valdes-Dapena, P. (2024, January 5). Hyundai and Kia thefts soar more than 1,000% since 2020. CNN. |

| 12. | Lopez, G. (2023, November 29). Is shoplifting really surging? The New York Times; Jones, J. M. (2023, November 16). More Americans see U.S. crime problem as serious. Gallup. |

| 13. | Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2024, April 2). Crime data explorer. https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend. |

| 14. | Asher, J. (2023, December 11). Crime in 2023: Murder plummeted, violent and property crime likely fell nationally. Jeff-alytics; Lopez, E., & Boxerman, B. (2024). Crime trends in U.S. cities: Year-end 2023 update. Council on Criminal Justice; Asher, J. (2024, April 2). It’s early, but murder is falling even faster so far in 2024. Jeff-alytics. |

| 15. | Robey, J., Massoglia, M., & Light, M. (2023). A generational shift: Race and the declining lifetime risk of imprisonment. Demography, p. 1. https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-10863378. For a broader discussion, see Ghandnoosh, N. (2023). One in five: Ending racial inequity in incarceration. The Sentencing Project. |

| 16. | John Jay College Research Advisory Group on Preventing and Reducing Community Violence. (2020). Reducing violence without police: A review of the research evidence. John Jay College of Criminal Justice; Sebastian, T., et al. (2022). A new community safety blueprint: How the federal government can address violence and harm through a public health approach. Brookings; Doleac, J. (2018). New evidence that access to health care reduces crime. Brookings. |

| 17. | Rovner, J. (2023). Youth justice by the numbers. The Sentencing Project. |

| 18. | Rate of change from 1999 to 2021. Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, T.J., and Kang, W. (2023). “Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement.” Available: https://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/ezacjrp/. |

| 19. | This is the FBI’s unadjusted count of total youth arrests (under age 18) representing 83% of law enforcement agencies nationwide. Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2024, April 2). Crime data explorer. https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend. |

| 20. | Even with this increase, youth accounted for just 11% of homicide arrests nationwide in 2022. Tapp, S.N., Thompson, A., Smith, E.L., Remrey, L. (2024). Crimes Involving Juveniles, 1993–2022. Bureau of Justice Statistics: Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2024, April 2). Crime data explorer. https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend. |

| 21. | Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2024, April 2). Crime data explorer. https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend |

| 22. | Tapp, S.N., Thompson, A., Smith, E.L., Remrey, L. (2024). Crimes Involving Juveniles, 1993–2022. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 23. | Tapp, S.N., Thompson, A., Smith, E.L., Remrey, L. (2024). Crimes Involving Juveniles, 1993–2022. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 24. | In contrast to rates of crime reported to the police during the 70s and 80s, rates of crime reported on victimization surveys fluctuated for violent crimes and decreased for property crimes during this period. Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2024, April 2). Crime data explorer. https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend; Beckett, K., & Sasson, T. (2004). The politics of injustice: Crime and punishment in America. Sage Publications; Lauritsen, J. L., Rezey M. L., & Heimer, K. (2016). When choice of data matters: Analyses of U.S. crime trends, 1973-2012. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 335-355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-015-9277-2 |

| 25. | Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2024, April 2). Crime data explorer. https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend. |

| 26. | Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2024, April 2). Crime data explorer. https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend. |

| 27. | Bureau of Justice Statistics. (1982). Prisoners 1925-81; Carson, E. A. (2022). Prisoners in 2021–Statistical tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics; Baumer, E. (2008). An empirical assessment of the contemporary crime trends puzzle: A modest step toward a more comprehensive research agenda. In A. Goldberger & R. Rosenfeld (Eds.), Understanding Crime Trends: Workshop Report (pp. 127–176). National Academies Press; Roeder, O., Eisen, L., & Bowling, J. (2015). What caused the crime decline? Brennan Center for Justice; Travis, J., Western, B., & Redburn, S. (Eds.) (2014). The growth of incarceration in the United States: Exploring causes and consequences. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. |

| 28. | Doob, A., & Webster, C. (2006). Countering punitiveness: Understanding stability in Canada’s imprisonment. Law & Society Review, 40(2), 325–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5893.2006.00266.x; Tseloni, A., Mailley, J., & Garrell, G. (2010). Exploring the international decline in crime rates. European Journal of Criminology, 7(5), 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370810367014; Tonry, M., & Farrington, D. P. (2005). Punishment and crime across space and time. Crime and Justice, 33, 1–39. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/faculty_articles/493 |

| 29. | Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2024, April 2). Sentenced prisoners under the jurisdiction of state or federal correctional authorities, December 31, 1978-2019. Corrections Statistical Analysis Tool (CSAT) – Prisoners. https://csat.bjs.ojp.gov/quick-tables |

| 30. | Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2024, April 2). Sentenced prisoners under the jurisdiction of state or federal correctional authorities, December 31, 1978-2019. Corrections Statistical Analysis Tool (CSAT) – Prisoners. https://csat.bjs.ojp.gov/quick-tables |

| 31. | Baumer, E. (2008). An empirical assessment of the contemporary crime trends puzzle: A modest step toward a more comprehensive research agenda. In A. Goldberger & R. Rosenfeld (Eds.), Understanding Crime Trends: Workshop Report (pp. 127–176). National Academies Press; Roeder, O., Eisen, L., & Bowling, J. (2015). What caused the crime decline? Brennan Center for Justice; Travis, J., Western, B., & Redburn, S. (Eds.) (2014). The growth of incarceration in the United States: Exploring causes and consequences. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. |

| 32. | Roeder, O., Eisen, L., & Bowling, J. (2015). What caused the crime decline? Brennan Center for Justice. |

| 33. | Travis, J., Western, B., & Redburn, S. (Eds.) (2014). The growth of incarceration in the United States: Exploring causes and consequences. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, p. 4. |

| 34. | “The best empirical evidence suggests that the successive iterations of the war on drugs – through a substantial public policy effort – are unlikely to have markedly or clearly reduced drug crime over the past three decades.” Travis, J., Western, B., & Redburn, S. (Eds.) (2014). The growth of incarceration in the United States: Exploring causes and consequences. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, p. 154. |

| 35. | See Ghandnoosh, N., Trinka, L., & Barry, C. (2024). One in five: How mass incarceration deepens inequality and harms public safety. The Sentencing Project. |

| 36. | See Ghandnoosh, N., & Nellis, A. (2022). How many people are spending over a decade in prison?. The Sentencing Project. |

| 37. | Nellis, A. (2021). No end in sight: America’s enduring reliance on life imprisonment. The Sentencing Project. |

| 38. | Ghandnoosh, N., & Nellis, A. (2022). How many people are spending over a decade in prison?. The Sentencing Project. |

| 39. | See Ghandnoosh, N., & Nellis, A. (2022). How many people are spending over a decade in prison?. The Sentencing Project. |

| 40. | United States Sentencing Commission. (2022). Length of incarceration and recidivism (2022); Antenangeli, L., & Durose, M. R. (2021). Recidivism of prisoners released in 24 states in 2008: A 10-year follow-up period (2008–2018). Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 41. | Kazemian, L. (2021). Pathways to desistance from crime among juveniles and adults: Applications to criminal justice policy and practice. National Institute of Justice; Blumstein, A., & Piquero, A. (2007). Restore rationality to sentencing policy. Criminology & Public Policy, 6(4), 679-687. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9133.2007.00463.x; Kazemian, L., & Farrington, D. P. (2018). Advancing knowledge about residual criminal careers: A follow-up to age 56 from the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Journal of Criminal Justice, 57, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2018.03.001; Piquero, A., Hawkins, J., & Kazemian, L. (2012). Criminal career patterns. In R. Loeber & D. P. Farrington (Eds.), From juvenile delinquency to adult crime: Criminal careers, justice policy, and prevention (pp. 14–46). Oxford University Press. |

| 42. | This peak is more pronounced in arrest trends between 1980 and 2010 and less so since then as arrest rates for young people have fallen dramatically. Loeber, R., & Farrington, D. (2014). Age-crime curve. Bruinsma & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. Springer, pp. 12–18; Neil, R., & Sampson, R. (2021). The birth lottery of history: Arrest over the life course of multiple cohorts coming of age, 1995–2018. American Journal of Sociology, 126(5), 1127–1178. https://doi.org/10.1086/714062; Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Statistical Briefing Book. Age-specific arrest rate trends. |

| 43. | Nagin, D. (2019, March 21). Guest post: Reduce prison populations by reducing life sentences. The Washington Post. |

| 44. | Robinson, P., & Darley, J. (2004). Does criminal law deter? A behavioral science investigation. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 24(2), 173–205. https://ssrn.com/abstract=660742 |

| 45. | The National Crime Victimization Survey collected participant responses as to why they did not report their victimization to police. The analysis showed people did not report their violent victimization to the police because they dealt with it in another way, e.g., handled informally as a private or personal matter or reported to another official (≈34%), thought it was not important enough to report (≈18%), had other reasons not specified (≈18%), thought police would not or could not do anything (≈16%), or feared reprisal or getting the person in trouble (≈13%); See Langton, L., & Berzofsky, M. (2012). Victimizations not reported to the police, 2006-2010. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 46. | Langton, L., & Berzofsky, M. (2012). Victimizations not reported to the police, 2006-2010. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 47. | Some arrests will correspond to more than one incident of violent victimization; FBI crime data explorer. Crime in the United States annual report, 2022: Estimated number of arrests, Table 29. FBI Uniform Crime Reporting Program. |

| 48. | The 36,380 individuals who were not sentenced to prison or jail in Figure 5 were likely sentenced to some form of community supervision; Rosenmerkel, S., Durose, M., & Farole Jr., D. (2010). Felony sentences in state courts, 2006 – Statistical tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 49. | Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime in the United States, 2006. United States Department of Justice; Rand, M. R., & Catalano, S. M. (2007). Criminal Victimization, 2006. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Violent victimization includes aggravated assault, robbery, rape, and the Uniform Crime Report murder/nonneglignent homicide count. |

| 50. | See, for example, Budd, K. M., & Bersani, B. (2020). Crimmigration: The presumption of illegality and the criminalization of immigrants. In G. W. Muschert, K. M. Budd, M. Christian, & R. Perrucci (Eds.), Agenda for social justice: Solutions for 2020 (pp. 105-113). Bristol, UK: Policy Press. 978-1-4473-5428-4; Farrell, G., Tilley, N. & Tseloni, A. (2014). Why the crime drop? Crime and Justice, 43(1), 421-490. https://doi.org/10.1086/678081; Zimring, F. E. (2007). The great American crime decline. Oxford University Press; Ghandnoosh, N., & Rovner, J. (2017). Immigration and public safety. The Sentencing Project. |

| 51. | Our data analysis begins in 2013 in order to use the revised Uniform Crime Report rape definition for each year included in the data analysis. Evidence also exists to support youth decarceration. In a 2011 report, the Annie E. Casey Foundation found “no correlation between juvenile confinement rates and violent youth crime.” The analysis showed that the states which decreased their juvenile confinement rates most sharply (40% or more) from 1997 to 2007 saw a greater decline in juvenile violent crime arrest rates than states that decreased incarceration moderately (20% to 40%), reduced juvenile confinement slightly (0% to 20%) or increased their youth confinement rates. See Mendel, R. A. (2011). No place for kids: The case for reducing juvenile incarceration. The Annie E. Casey Foundation, p. 26. |

| 52. | Meachum, A. (2024, March 28). Shreveport police chief releases latest crime statistics. 6KTALnews.com; Webster, R. A. (2024, April 1). ‘Everyone will die in prison’: How Louisiana’s plan to lock people up longer imperils its sickest inmates. New Orleans Public Radio, WWNO 89.9; Wilkinson, M. (2024). New Orleans saw violent crime fall across many categories in 2023, data shows. Nola.com; City Council of New Orleans. Crime Dashboard – Main. |

| 53. | Cline, S. (2024, February 29). A look at the tough-on-crime bills Louisiana lawmakers passed during a special session. Associated Press; Rojas, R. (2024, March 4). With sweeping new laws, Louisiana embraces tough-on-crime approach. The New York Times. |

| 54. | See, for example, French, P. (2024, March 4). “We’re going to be overwhelmed”: How Louisiana just ballooned its jail population. Bolts; Hutson, S. (2024, March 24). New criminal-justice laws bring unforeseen consequences. The Lens. |

| 55. | Dunphey, K. (2024, March 11). With new laws, is Utah holding criminals accountable or adding to mass incarceration? Utah News Dispatch. |

| 56. | U.S. Sentencing Commission. (2020). Retroactivity & recidivism: The drugs minus two amendment; U.S. Sentencing Commission. (2018). Recidivism among federal offenders receiving retroactive sentence reductions: The 2011 Fair Sentencing Act guideline amendment; U.S. Sentencing Commission. (2014). Recidivism among offenders receiving retroactive sentence reductions: The 2007 crack cocaine amendment. |

| 57. | Recidivism was defined broadly in this study, as reconviction, rearrest, or revocation of supervised release. U.S. Sentencing Commission. (2020). Retroactivity & recidivism: The drugs minus two amendment; U.S. Sentencing Commission. (2018). Recidivism among federal offenders receiving retroactive sentence reductions: The 2011 Fair Sentencing Act guideline amendment; U.S. Sentencing Commission. (2014). Recidivism among offenders receiving retroactive sentence reductions: The 2007 crack cocaine amendment. |

| 58. | Prosecutors wield enormous power in the flow of individuals through the criminal legal system. Much of their decisionmaking occurs behind closed doors, away from public view and scrutiny. See: Sklansky, D. A. (2016). The nature and function of prosecutorial power. J. Crim. L. & Criminology, 106, 473. |

| 59. | Komar, L., & Porter, N. (2023). Ending mass incarceration: Safety beyond sentencing. The Sentencing Project. |

| 60. | Ghandnoosh, N. (2017). Opioids: Treating an illness, ending a war. The Sentencing Project. |

| 61. | Mendel, R. (2022). Diversion: A hidden key to combating racial and ethnic disparities in juvenile justice. The Sentencing Project; Mendel, R. (2023). Effective alternatives to youth incarceration. The Sentencing Project. |

| 62. | Komar, L., & Porter, N. (2023). Ending mass incarceration: Safety beyond sentencing. The Sentencing Project. |

| 63. | Petrich, D. M., Pratt, T. C., Jonson, C. L., & Cullen, F. T. (2021). Custodial sanctions and reoffending: A meta-analytic review. Crime and Justice, 50(1), 353–424. https://doi.org/10.1086/715100; Loeffler, C. E., & Nagin, D. S. (2022). The impact of incarceration on recidivism. Annual Review of Criminology, 5(1), 133–152. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-030920-112506; Bales, W. D., & Piquero, A. R. (2012). Assessing the impact of imprisonment on recidivism. Journal of Experimental Criminology (8), 71–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-011-9139-3 |

| 64. | See, for example, Phelps, M. S. (2013). The paradox of probation: Community supervision in the age of mass incarceration. Law & Policy, 35(1-2), 51-80. https://doi.org/10.1111/lapo.12002 |

| 65. | Lopoo, E., Schiraldi, V., & Ittner, T. (2023). How little supervision can we have? Annual Review of Criminology, 6, p. 23. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-030521-102739 |

| 66. | Mendel, R. (2023). Effective alternatives to youth incarceration. The Sentencing Project; and Mendel R. (2023). System reforms to reduce youth incarceration: Why we must explore every option before removing any young person from home. The Sentencing Project. |

| 67. | Komar, L., Nellis, A., & Budd, K. M. (2023). Counting down: Paths to a 20-year maximum prison sentence. The Sentencing Project. |

| 68. | Kazemian, L. (2021). Pathways to desistance from crime among juveniles and adults: Applications to criminal justice policy and practice. National Institute of Justice; Blumstein, A., & Piquero, A. (2007). Restore rationality to sentencing policy. Criminology & Public Policy, 6(4), 679-687. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9133.2007.00463.x; Kazemian, L., & Farrington, D. P. (2018). Advancing knowledge about residual criminal careers: A follow-up to age 56 from the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Journal of Criminal Justice, 57, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2018.03.001; Piquero, A., Hawkins, J., & Kazemian, L. (2012). Criminal career patterns. In R. Loeber & D. P. Farrington (Eds.), From juvenile delinquency to adult crime: Criminal careers, justice policy, and prevention (pp. 14–46). Oxford University Press. |

| 69. | United States Sentencing Commission. (2022). Length of incarceration and recidivism (2022); Antenangeli, L., & Durose, M. R. (2021). Recidivism of prisoners released in 24 states in 2008: A 10-year follow-up period (2008–2018). Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 70. | Muhammad, K. G., Western, B., Negussie, Y., & Backes, E. (Eds.) (2022). Reducing racial inequality in crime and justice: science, practice, and policy. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Ghandnoosh, N., Barry, C., & Trinka, L. (2023). One in five: Racial disparity in imprisonment – causes and remedies. The Sentencing Project. |

| 71. | Nellis, A. (2024). How mandatory minimums perpetuate mass incarceration and what to do about it. The Sentencing Project. |

| 72. | Robert, A. (2022, August 8). ABA provides 10 principles for ending mass incarceration and lengthy prison sentences. ABA Journal. |

| 73. | American Law Institute. (2021). Model Penal Code: Sentencing. Prepublication Draft, p. 802. |

| 74. | Nellis, A. (2021). The color of justice: Racial and ethnic disparities in state prisons. The Sentencing Project. |

| 75. | Porter, N. D. (2023). Testimony in support of Rhode Island’s Equity Impact Statement Act. The Sentencing Project. |

| 76. | Porter, N. D. (2023). Testimony in support of Rhode Island’s Equity Impact Statement Act. The Sentencing Project. |