Protect and Redirect: How to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Juvenile Diversion

This brief suggests practical steps that advocates, system leaders, and in some cases legislators can take to address disparities in diversion, including many examples where these suggested reforms are being implemented effectively.

Related to: Youth Justice

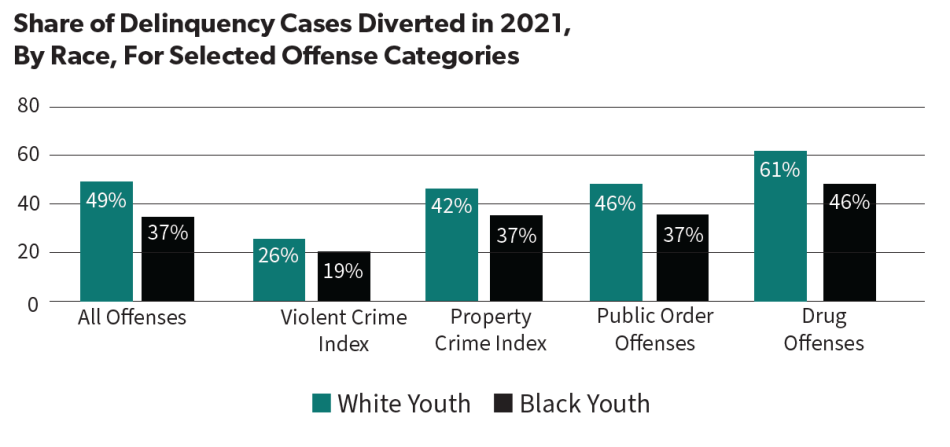

The early stages of the youth justice process – arrest and the decision whether to formally process in court rather than divert delinquency cases – are plagued by large and consequential racial and ethnic disparities.1 Although available evidence suggests little difference in offending rates for most lawbreaking behaviors, Black youth were arrested 2.3 times as often as white youth nationwide in 2020, while Tribal youth were arrested 1.7 times as often as white youth.2 Among delinquency cases referred to juvenile court, 50% of those involving white youth were diverted, far higher than the share of cases diverted involving Black youth (39%) and Tribal youth (38%), and slightly higher than Latinx and Asian American youth (both 48%).3 Overwhelming research finds that disparities at arrest and court intake are driven at least partly by biased decision-making that treats white youth more favorably than comparable peers who are Black, Latinx, or Tribal 4 Bias in these early stages is a key factor driving the large disparities in incarceration that continue to plague youth justice systems nationwide.5

Expanding the use of pre-arrest and pre-court diversion, especially for youth of color, is an essential priority for reducing racial and ethnic disparities and promoting greater equity in youth justice. Fortunately, many effective strategies are available at both the state and local levels to accomplish this goal.6 This brief suggests practical steps that advocates, system leaders, and in some cases legislators can take to address disparities in diversion, including many examples where these suggested reforms are being implemented effectively.

Identify and address points of significant disparity

The most comprehensive method to reduce disparities in diversion is to collect and analyze diversion data – breaking down the data by race and ethnicity to determine where disparities are most pronounced. Advocates and system leaders can then strategize and craft new approaches designed to reduce disparities at the problematic decision points. Specifically, state and local justice system leaders should review data on:

- What are the most common offenses for which youth are being referred to court? And for which of the common offenses are disparities most prevalent? In particular, system leaders should look to identify offenses that are appropriate for diversion (all but the most serious violent offenses) and for which arrests primarily include youth of color.

- What share of youth from different racial and ethnic groups are being offered diversion, and how do these rates differ based on the offenses for which youth are referred to court?

- Among youth offered diversion, does the share who actually participate (as opposed to rejecting diversion or not responding to invitations to participate) differ by race and ethnicity?

- Among youth who enroll in diversion, how do success rates differ by race and ethnicity? Are there pronounced disparities in the share of youth returned to court for failure or noncompliance with diversion?

Numerous jurisdictions in recent years have made strides to reduce diversion disparities by conducting these kinds of analyses and convening stakeholder teams to use the data to craft new approaches aimed at reducing disparities.

Pennsylvania

In Pennsylvania, six of seven counties participating in the Georgetown University Center for Juvenile Justice Reform’s Advancing Racial Justice and Equity in Youth Legal Systems Certificate Program since 2021 have focused on pre-arrest or pre-court diversion.7 Participating county teams received an intensive week-long training on racial equity in youth justice, conducted intensive data analysis, and then devised and implemented plans to advance diversion strategies that reduce disparities. Both Philadelphia and Allegheny County (Pittsburgh) focused on adapting pre-arrest diversion programs already offered to youth in their public schools to also divert youth apprehended in the community. Other counties developed new school-based pre-arrest diversion programs, expanded eligibility for diversion, and increased enrollment in diversion by assisting eligible youth with necessary paperwork.8 Though these efforts remain in the early implementation stages, a 2023 report documented encouraging early outcomes in two participating counties: more use of diversion overall and a greater share of diversion opportunities going to Black and Latinx youth.9

New York

Teams from five upstate counties in New York took part in a weeklong training in 2021 to review data and assess their diversion policies and practices,10 as part of a Policy Equity Academy funded by the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention and the Annie E. Casey Foundation.11 The academy required each county to identify and develop plans to address three priority challenges related to racial and ethnic equity in diversion. In their plans, several counties have revised the documents they send to youth and families eligible for diversion and taken other steps to reduce the share of families offered diversion who decline to participate. Multiple sites have begun to employ “credible messengers” – adults with personal history in the justice system or other lived experiences in common with many youth – to enhance the effectiveness of their diversion programs.12 In Onondaga County (Syracuse), for instance, the local team devised plans to reduce the number of youth formally petitioned in court for not attending required appearances in family court; reduce arrests for youth under age 12; and reduce the number of parents who refuse diversion and instead request formal court processing.13

California

In supporting a nationwide network of restorative justice diversion programs, Equal Justice USA14 makes reducing racial and ethnic disparities a core focus. Specifically, participating sites analyze local data to identify zip codes with high rates of incarceration for youth of color and specific offense categories for which youth of color are arrested disproportionately. Participating sites use these data to determine where to focus their programs geographically, and which offenses should be highlighted for restorative justice diversion.15) In Alameda County (Oakland), California, a recent evaluation found that participants in a restorative justice diversion program had far lower recidivism than comparable peers who were formally processed in court (20% vs. 37% after 18 months); 88% of participating youth were Black or Latinx, and all participants were accused of felonies or serious misdemeanors that would otherwise have resulted in probation or placement in a residential facility.16 As Equal Justice USA explains in its Diversion Toolkit for Communities, “When we try to reduce numbers without directly and consciously addressing RED [racial and ethnic disparities], RED will always increase. RED can only be reduced through explicit, concerted, and sustained effort.”17

Kentucky

In Kentucky, legislation passed in 201418 aimed to significantly expand the use of diversion, making it the presumed outcome for all youth arrested for misdemeanor offenses statewide 19 However, early results showed that the new law was benefiting white youth far more than Black youth.20 When leaders in the state’s Administrative Office of the Courts examined the data, they found that the worsening disparities were tied to two issues:

- First, many youth, especially Black youth, were not enrolling in diversion even after they were deemed eligible. In response, the court system changed its protocols for informing youth and families about diversion: Rather than sending a form letter about diversion and dictating the time and place for an intake interview, staff began calling families, explaining the benefits of diversion, and asking when a meeting would be convenient. Participation rates increased sharply, especially for Black youth.21

- Second, Kentucky’s data showed that prosecutors and judges were rejecting diversion opportunities – overriding recommended use of diversion – far more often for Black youth than for white youth. To correct this problem, leaders at the Administrative Office of the Courts partnered with a racial equity advocate and reached out to judges and prosecutors with high override rates, showed them the data, and encouraged them to review their override practices. As a result, override rates fell sharply in some jurisdictions, including a 91% reduction in prosecutorial overrides for Black youth in Jefferson County, which is home to Louisville and the state’s most populous county.22

Iowa

Since teams from several Iowa counties participated in a workshop on racial and ethnic disparities in 2012, the state has seen a growing number of targeted diversion programs. Data analysis in Johnson County (Iowa City) showed that police made more arrests of Black youth than white youth in 2012 – even though white youth in the county outnumbered Black youth nearly 8 to 1.23 The disparities were especially alarming in arrests for disorderly conduct: 57 arrests for Black youth versus 11 for white youth.24 To begin addressing the disparities, local leaders developed a diversion program specifically for youth accused of disorderly conduct. Subsequently, Johnson County added a diversion program for shoplifting,25 and it recently began offering diversion for all simple misdemeanors.26 Scott County (Davenport) and Webster County (Fort Dodge) also began offering diversion programs targeted to offenses with large disparities.27 After studies showed that diverted youth had very low recidivism, Iowa passed legislation in 201828 encouraging counties throughout the state to offer pre-charge diversion programs,29 and since 2021 the state has made competitive grant funding available to support diversion in counties statewide.30 Pre-charge diversion programs served nearly 1,400 Iowa youth from 2015-2022, more of whom were Black than white.31 By diverting large numbers of Black youth in a state where Black youth make up just 7% of the youth population,32 the pre-charge diversion programs are helping reduce racial disparities among cases formally processed in delinquency courts. State data show that recidivism among diverted youth (11%) was roughly a third that of youth facing low-level charges whose cases were overseen by juvenile courts (30%).33

At least 20 academic studies over the past 25 years have detected significant racial or ethnic bias in decisions regarding formal processing of delinquency cases referred to juvenile court. These studies have found disparities in diversion all across the country.Quote from: DIVERSION: A Hidden Key to Combating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Juvenile Justice, The Sentencing Project, August 2022

Change diversion-related laws, rules, or practices that disadvantage youth of color

Many common and longstanding practices for diversion contradict research on best practices and unnecessarily exclude youth of color or lower their likelihood of success.34 Reforming these practices represents an important strategy for reducing disparities and promoting racial and ethnic equity.

- Rewrite rules limited diversion to very low-level offenses, and give youth repeated opportunities for diversion, rather than offering diversion only on first or second arrests and only for low-level offenses.

Several studies have found that diversion reduces the likelihood of recidivism as much or more for youth accused of more serious crimes as it does for youth accused of petty crimes.35 Also, there is no evidence that offering repeated opportunities for diversion erodes its advantageous impact.36 Given the far higher arrests rates for youth of color, these rules exclude youth of color from diversion disproportionately. In keeping with this research, several jurisdictions in recent years have broadened the list of offenses for which youth can be diverted,37 and several have eased rules limiting diversion to youth facing arrest for the first-time.38 For instance, Los Angeles County has launched a pre-arrest diversion program intended to serve all youth apprehended for misdemeanors and most nonviolent felonies.39 Washington state’s legislature enacted reforms in 2018 mandating diversion for first-time misdemeanor offenses, extending eligibility for diversion to youth accused of all subsequent misdemeanors and some felonies, and eliminating limits on the number of times youth can be diverted.40

- Improve outreach to increase the likelihood that youth offered diversion participate.

In many jurisdictions, a substantial share of eligible youth, particularly youth of color, never enter diversion due to inadequate outreach.41 As described above, Kentucky has changed its procedures for informing youth of diversion opportunities and scheduling initial intake meetings; as a result, the overall share of youth offered diversion who failed to appear fell 40%; for Black youth, it fell 46%.42

- Eliminate fines and fees for diversion, and ensure that restitution obligations are fair and realistic for youth of limited means.

Courts or probation often require youth and their families to pay fines and fees as a condition to participate in diversion programming, creating an unnecessary barrier to participation and success.43 Research finds that fines and fees harm youth of color disproportionately and increase re-offending.44 In April 2023, the U.S. Department of Justice issued a letter encouraging state and local justice systems to “eliminate fines and fees imposed on youth in the juvenile legal system.”45 In line with this guidance, a growing number of states and localities have eliminated or capped diversion fines and fees (as well as fees for probation), and legislation is pending in many other jurisdictions.46 Some jurisdictions have also taken steps to limit restitution obligations, either through victim compensation funds or by limiting restitution requirements based on the young person’s and family’s ability to pay.47 Also, experience finds that diversion programs employing a restorative justice approach often result in lower restitution requirements and greater payment rates than court-imposed restitution obligations. For instance, in Los Angeles County, a recent study found that youth participating in the Centinela Youth Services pre-arrest diversion program, which includes a restorative justice component, paid vastly more monetary restitution than youth ordered to pay restitution by a court – even though their required restitution orders were often far smaller.48

- Eliminate requirements that youth admit guilt as a condition for participation.

Many jurisdictions require youth to make a formal admission of guilt in order to participate in diversion. This requirement can exacerbate disparities because youth of color and their families – who are less likely than whites to trust the justice system – are often more hesitant to admit guilt.49 While taking responsibility for one’s actions is a necessary ingredient for restorative justice, it does not require a formal admission of guilt. Rather, as argued in a recent review of diversion research, “flexible criterion of ‘accepting responsibility’ should be used rather than requiring a formal admission of guilt.”50 The Sentencing Project is not aware of any evidence showing that admission of guilt is necessary or beneficial in other types of diversion programming.

- Reduce the share of diverted youth returned to court for noncompliance by changing policies and adopting practices to help youth comply with diversion requirements, such as attendance at mandated activities and completion of mandated community service and restitution

Given the much worse outcomes (higher recidivism, less success in school and career) associated with formal involvement in the justice system, and the higher failure rates experienced by youth of color,51 it is counterproductive to punish noncompliant behavior among diverted youth by filing charges and prosecuting them in court. “Absent serious subsequent offenses, diverted youth should not be subject to court-ordered conditions,” the Center for Children’s Law and Policy concluded in a recent publication. “[N]oncompliance with diversion agreements should usually be addressed with a warning. If a young person fails to complete a diversion agreement, he or she is better left to grow and mature under family supervision.”29 To reduce failure rates in diversion, two states have taken targeted action in recent years. As part of its reforms in 2014, Kentucky required every county to create a multidisciplinary Family Accountability, Intervention and Response (FAIR) team to intervene and create enhanced case management plans for youth in diversion who have high needs or who struggle to comply with diversion requirements. In 2020, an evaluation found that the FAIR teams appeared to be increasing the success rates of youth on diversion and reducing subsequent recidivism.53

In Kansas, a comprehensive juvenile justice reform law enacted in 201654 requires each juvenile court across the state to create a multidisciplinary team to review the cases of youth who do not comply with diversion rules.55

Conclusion

The evidence is overwhelming that youth of color, and especially Black youth, are offered diversion far less often than white youth, and that unequal treatment at the diversion stage is a major driver of subsequent disparities in incarceration. As documented in this brief, many strategies have proven capacity to combat disparities. Pursuing these strategies should be a top priority for states and local justice systems.

| 1. | Mendel, R. (2022). Diversion: A hidden key to combating racial and ethnic disparities in juvenile justice. The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | OJJDP Statistical Briefing Book. Arrest rates by offense and race, 2020 (rates are per 100,000 in age group) (2022). |

| 3. | Sickmund, M., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2022). Easy Access to Juvenile Court Statistics: 1985-2020. |

| 4. | Mendel (2022), see note 1. |

| 5. | Mendel (2022), see note 1. |

| 6. | Mendel (2022), see note 1. |

| 7. | Ogle, M.R. (2023). Advancing racial equity in pennsylvania’s youth legal system. Center for Juvenile Justice Reform, McCourt School of Public Policy, Georgetown University. |

| 8. | Ogle (2023), see note 7. |

| 9. | Ogle (2023), see note 7; Specifically, in one participating county (Montgomery) the white share of youth referred to the Youth Aid Panel diversion program fell from 65% to 57% after the capstone project was implemented; and in another county (Lehigh) the share of Hispanic youth diverted tripled in the first year of the capstone project. |

| 10. | Medelis, K.P. & Victorio, V. ( 2021, July 15). New York project aims to narrow gap between minority versus white juvies sent to community programs, not prison. Juvenile Justice Information Exchange. |

| 11. | New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services. (2021, June 30). New York State announces creation of new Policy Equity Academy to address racial and ethnic disparities in the state’s youth justice system [Press release]. |

| 12. | Lopes, G. & Irons, D., of Youth Justice Institute, personal communication, November 7, 2023; Deame, T., & Conley, K., of NYS Division of Criminal Justice Services, personal communication, November 7, 2023. |

| 13. | Damian Pratt, Director of Juvenile Justice & Detention Services at Onondaga County Department of Children & Family Services, personal communication, October 17, 2023. |

| 14. | From 2011 until November 2023, the Restorative Justice Diversion project was overseen by Impact Justice, a nonprofit justice reform organization based in Oakland, CA. In November 2023, responsibility for the project was transferred to Equal Justice USA, based in Brooklyn, NY. Equal Justice USA Welcomes the Restorative Justice Project (2023, November 17). Equal Justice USA. |

| 15. | Equal Justice USA (n.d.). A restorative justice toolkit for communities: Step 1D. What is our approach to RJD? (See Core Element 3: Designed to reduce the criminalization of BIPOC communities. |

| 16. | Baliga, S., Henry, S., & Valentine, G. (2017). Restorative Community Conferencing: A study of Community Works West’s restorative justice youth diversion program in Alameda County. Impact Justice. |

| 17. | Equal Justice USA (n.d.). A restorative justice toolkit for communities: Step 1D. What is our approach to RJD? (See Core Element 3: Designed to reduce the criminalization of BIPOC communities.) |

| 18. | Kentucky’s 2014 juvenile justice reform. (2014). Pew Charitable Trusts. |

| 19. | Kentucky’s 2014 juvenile justice reform (2014), see note 18. |

| 20. | Howard, K. (2018). Kentucky Reformed Juvenile Justice, And Left Black Youth Behind. Louisville Public Media. |

| 21. | Bingham R., director of Family and Justice Services, Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts, personal communication, April 15, 2022; Bingham, R. (2020). Kentucky’s racial and ethnic disparities efforts. Coalition for Juvenile Justice. |

| 22. | Palmer E. & Bingham, R. (2021). Don’t hate the player, hate the game: The importance of systemic change to address racial and ethnic disparities. The Juvenile Justice Update 27(1). |

| 23. | Johnson County diversion program to offer youth a chance to avoid court. (2014, June 26). The [Cedar Rapids] Gazette. |

| 24. | Johnson County diversion program to offer youth a chance to avoid court. (2014, June 26), see note 23. |

| 25. | Ojeda, H. (2018, September 27). Johnson County juvenile justice diversion program has State officials paying attention. Iowa City Press-Citizen. |

| 26. | Pre-charge diversion coordination and expansion program: Request for proposals. (2022). Johnson County Pre-Charge Diversion Coordination and Expansion Program. |

| 27. | Iowa pre-charge diversion toolkit (n.d.). Center for Children’s Law and Policy. |

| 28. | Iowa House Bill 2443 (Prior Session Legislation). (2017). LegiScan. https://legiscan.com/IA/bill/HF2443/2017 |

| 29. | Iowa pre-charge diversion toolkit (n.d.), see note 27. |

| 30. | Iowa’s delinquency prevention strategy – pre-charge diversion. (2021). Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; and Iowa Department of Human Rights; State Fiscal Year 2023/24 Juvenile Delinquency Prevention – Pre-Charge Diversion CDFA/Assistance Listing #16.548 (2023). Iowa Department of Human Rights. |

| 31. | Pre-charge diversion: statewide results (SFY 2015-2022) (n.d). Iowa Criminal & Juvenile Justice Planning. |

| 32. | Easy access to juvenile populations: 1990-2020. (2021). Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. |

| 33. | Pre-charge Diversion: Statewide Results, see note 31. |

| 34. | Mendel (2022), see note 1. |

| 35. | Beckman, K. J., Jewett, P. I., Gaҫad, A., & Borowsky, I. W. (2023). Reducing Re arrest Through Community-Led, Police-Initiated Restorative Justice Diversion Tailored for Youth. Crime & Delinquency; and Mendel, R. (2022), see note 1. |

| 36. | Mendel (2022), see note 1. |

| 37. | For example: Juvenile Justice System; SB 367 (Legislation Summary) (2016). Kansas State Legislature; Justice for Kids and Communities Legislative Package. (n.d.) Michigan Center for Youth Justice; Gibbons, L. (2023). Michigan lawmakers vote to end most juvenile court fees, citing harms. Bridge Michigan; Utah’s 2017 Juvenile Justice Reform Shows Early Promise: Law aims to improve public safety outcomes across the state (2019). Pew Charitable Trusts Public Safety Improvement Project; Washington State Engrossed Substitute Senate Bill 6550. (2018). Washington State Legislature. |

| 38. | For Example: Juvenile Justice System; SB 367 (Kansas), see note 37; Washington State Engrossed Substitute Senate Bill 6550, see note 37. |

| 39. | Fremon, C. (2017). Los Angeles board of supervisors votes to launch ‘historic’ juvenile diversion plan. Juvenile Justice Information Exchange. |

| 40. | Engrossed Substitute Senate Bill 6550. Washington State Legislature. (2018). |

| 41. | Mendel (2022), see note 1. |

| 42. | Harvell, S., Sakala, L., Lawrence, D. S., Olsen, R., & Hull, C. (2020). Assessing juvenile diversion reforms in Kentucky. Urban Institute Justice Policy Center; Palmer E. & Bingham, R. (2021), see note 22. |

| 43. | Feierman, J., Goldstein, N., Haney-Caron, E., & Fairfax Columbo, J. (2016) Debtors’ prison for kids? The high cost of fines and fees in the juvenile justice system. Juvenile Law Center. |

| 44. | Mendel (2022), see note 1 |

| 45. | Gupta, V. (2023). Dear Colleague Letter to Courts Regarding Fines and Fees for Youth and Adults. U.S. Department of Justice. |

| 46. | Friedrich, M. (2022). A nationwide campaign to end juvenile fines and fees is making progress. Arnold Ventures. |

| 47. | Smith, L., Mozaffar, N., Feierman, J., Parker, L., NeMoyer, A., Goldstein, N., Hall Spence, J., Thompson, M., & Jenkins, V. (2022). Reimagining restitution: New approaches to support youth and communities. Juvenile Law Center. |

| 48. | Ellis, J. & Scott, W. (2023). Restorative justice diversion for young people [Webinar]. Annie E. Casey Foundation. |

| 49. | Schlesinger, T. (2018). Decriminalizing racialized youth through juvenile diversion. Future of Children, 28(1), 1-23. |

| 50. | Robin-D’Cruz, C. & Whitehead, S. (2021). Disparities in youth diversion – an evidence review. Center for Justice Innovation. |

| 51. | Mendel (2022), see note 1 |

| 52. | Iowa pre-charge diversion toolkit (n.d.), see note 27. |

| 53. | Harvell et al (2020), see note 42. |

| 54. | Kansas’ 2016 juvenile justice reform law (2017). Pew Charitable Trusts. |

| 55. | Immediate intervention program standards. (2017). Kansas Department of Corrections- Division of Juvenile Services. |