Protect and Redirect: America’s Growing Movement to Divert Youth Out of the Justice System

Jurisdictions across the country are advancing reforms to expand and improve diversion, demonstrating diversion’s potential to transform youth justice in ways that protect public safety and enhance youth success.

Related to: Youth Justice, Racial Justice

After decades of neglect, the youth justice field is awakening to the importance of diversion in lieu of arrest and formal court processing for many or most youth accused of delinquent behavior. Even amid rising concerns over youth crime nationwide, jurisdictions across the country are heeding the evidence by taking concerted action to address more cases of alleged lawbreaking behavior outside the formal justice system. This momentum to make diversion a centerpiece of juvenile justice reform is encouraging given powerful research showing that youth who are diverted from the justice system are far less likely to be arrested for subsequent offenses and far more likely to succeed in education and employment than comparable youth who are arrested and prosecuted in juvenile court. Greater use of diversion is also essential to reduce the persistent racial and ethnic disparities that pervade youth justice systems.

This brief details significant diversion reform efforts of several types.

Many jurisdictions have taken steps in the past five to 10 years to expand diversion opportunities for youth by creating new laws, programs, or pathways to increase the use of diversion – and in some cases by mandating or otherwise compelling the use of diversion in some types of cases. Several jurisdictions have embraced new approaches to ensure that lower-risk youth with significant human services needs are handled outside the justice system. More than a dozen states have raised the minimum age for involvement in delinquency court – meaning that youth under the new age thresholds are automatically diverted.

A number of states and localities have taken significant steps to promote racial and ethnic equity in diversion. Some jurisdictions have created multidisciplinary teams, compiled and analyzed data, and undertaken comprehensive reviews to identify and address problematic practices that have been causing diversion disparities. Others have been revising diversion-related laws, rules, or practices that often disadvantage youth of color.

In other jurisdictions, justice system leaders are making changes to improve diversion practices and increase the success of youth once diverted. For instance, there is growing momentum to support the use of restorative justice diversion programs, which aim to engage youth in repairing the harm caused by their behavior. And there is growing interest in expanding opportunities for youth to be diverted prior to arrest, which is even more advantageous than diverting youth after they’ve been arrested and referred to court. Other jurisdictions are taking steps to reduce the failure rates of youth in diversion and to minimize the share who are returned to court for noncompliance with diversion.

Many jurisdictions have improved the collection and sharing of data to better inform diversion policies and programs. A number of states have significantly expanded data collection and reporting requirements for diversion. Other states and localities have begun to measure diversion outcomes against new success metrics, or created new data dashboards to make information on diversion participation and results available to a wide audience.

Background

Diversion is the decision to address a young person’s alleged misconduct outside of the formal justice system, either prior to an arrest being made or after referral to juvenile court on delinquency charges. Diversion has long been an option in the juvenile justice system, but it has received little attention in policy debates or media coverage of youth justice. Diversion, therefore, remains poorly understood by the public.1 Historically, and to this day, diversion has often been misused. It has remained underutilized for youth who would most benefit – those who pose manageable risks to public safety but would otherwise be prosecuted in court and exposed to counterproductive sanctions in the juvenile court process and their resulting collateral consequences.2 At the same time, diversion programs have often been imposed unnecessarily on youth who pose minimal risk to the public who would otherwise not be involved in the justice system at all, a phenomenon known as net-widening.3

Compelling evidence finds that arrests and formal involvement in the justice system are counterproductive both for public safety and youth well-being.4 Research studies consistently find that being arrested in adolescence substantially increases the likelihood of future justice system involvement, and it reduces future success in school and work.5 Studies also find that once arrested, youth who are formally charged in juvenile courts do far worse than those whose cases are diverted from court on many measures of public safety and youth well-being.5 Also, compelling evidence shows that decisions at the early stages of the justice system process – those that involve diversion as an alternative to arrest, or to formal processing in court – suffer from substantial biases against youth of color, and that these biased decisions around diversion are an important driver of subsequent disparities in confinement.5

In the most comprehensive and ambitious study ever undertaken…Diverted youth had equal or better outcomes on all 19 outcome measures!

| Indicators with Better Results for Diverted Youth | Indicators With No Statistically Significant Difference | Indicators with Better Results for Youth Formally Processed in Court |

|---|---|---|

| Likelihood of Re-Arrest | Self-Report of Total Offending | None |

| Likelihood of Subsequent Incarceration | Self-Report of Physical Aggression | |

| Self-Report of Violent Behavior | Currently Employed | |

| Current School Enrollment | Mental Health-Internalizing Problems | |

| School Enrollment or Employment | Mental Health-Interpersonal Callousness | |

| High School Graduation Within 5 Years | Impulse Control | |

| Ability to Suppress Aggression | Consideration of Others | |

| Perception of Future Opportunities | Sensation Seeking | |

| Association With Delinquent Peers | Future Orientation | |

| Exposure to Violence |

Source: Cauffman, E., Beardslee, J., Fine, A., Frick, P.J. & Steinberg, L. (2021). Crossroads in Juvenile Justice: The impact of the initial Processing Decision on Youth Five Years After Arrests. Development and Psychopathology 33:2, 700-713.

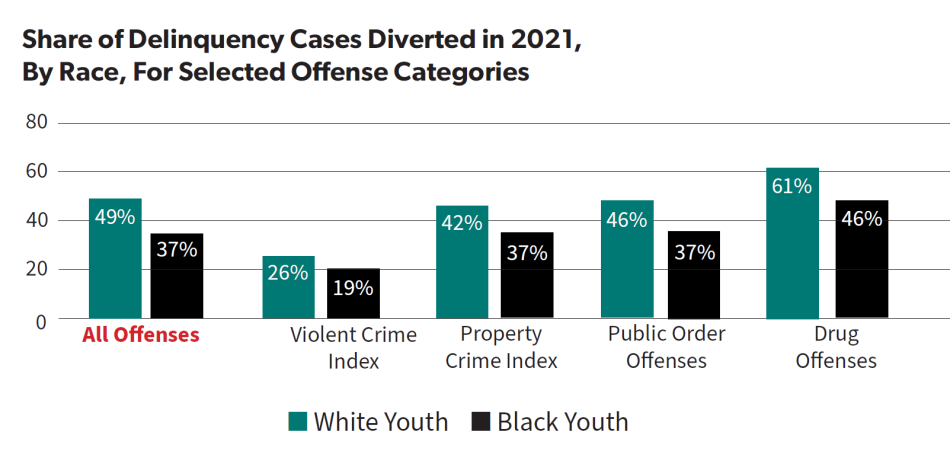

Share of Delinquency Cases Diverted in 2021, By Race, For Selected Offense Categories

As The Sentencing Project documented in its 2022 report Diversion: A Hidden Key to Combating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Juvenile Justice, there are many reform opportunities available at both the state and local levels to expand and improve the use of diversion, and to reduce disparities.5

Across the country, jurisdictions are seizing these opportunities by advancing reforms to expand and improve diversion. These efforts are demonstrating diversion’s potential to transform youth justice in ways that protect public safety, enhance youth success, and – thanks to growing use of restorative justice strategies – increase the justice system’s capacity to meet the needs of those harmed by adolescent misbehavior.

This brief provides an overview of the substantial advances that jurisdictions are making on juvenile diversion all over the nation. States and local justice systems have advanced an impressive array of new diversion efforts over the past decade or more, sometimes on their own, and sometimes with expert support from national technical assistance providers at the Council of State Governments Justice Center, Georgetown University Center for Juvenile Justice, the Center for Children’s Law and Policy, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Impact Justice, the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Public Safety Improvement Project, and other organizations.

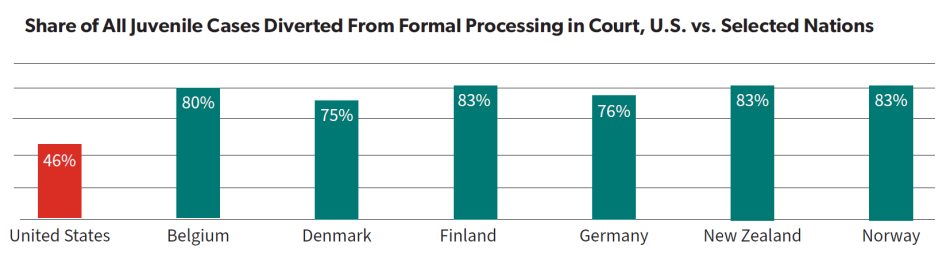

To date, these diversion reform efforts have mostly flown under the radar in terms of media attention, but taken together they represent a noteworthy shift in youth justice policy that could – and should – represent the beginning of a meaningful national movement to make diversion the norm for addressing most delinquent conduct by America’s adolescents.

Across the country, many states and localities have taken noteworthy steps in recent years to increase the use of diversion for youth accused of delinquent conduct.

Share of All Juvenile Cases Diverted From Formal Processing in Court, U.S. vs. Selected Nations

Expanding Diversion Opportunities

Significant New Laws, Programs, and Pathways to Expand the Use of Diversion.

Accelerating a trend that began in the previous decade, many state and local justice systems have created new diversion rules and pathways in the past few years that substantially expand the share of youth diverted prior to arrest, at intake (prior to a petition being filed for youth who are referred to court on delinquency charges), or both.

- Kansas – As part of a comprehensive juvenile justice reform law passed in 2016,9 Kansas created a new diversion option, the Immediate Intervention Program (IIP).10 The law mandated IIP’s use for youth accused of first-time misdemeanors and authorized it for all misdemeanor offenses. Nearly 2,000 youth were referred to IIP as a diversion from formal court processing in fiscal year 2022,11 of whom 92% successfully completed diversion12 by complying with the terms of their diversion agreements and avoiding a new adjudication or conviction.13

- New Hampshire – Since 2017, New Hampshire has dramatically expanded the use of diversion. The state created several new behavioral health interventions and initiated a new process to conduct behavioral health screens for all youth referred to juvenile court. The state now diverts most youth to behavioral health rather than court interventions: 72% of youth assessed through the new process in 2022 were recommended to non-court interventions, and police supported the recommendations 94% of the time.14 As a result, new delinquency cases in the state dropped 50% from 2018 to 2022.15

- Indiana – In a comprehensive 2022 juvenile justice reform law, Indiana created a new grant program that will provide state funding to support local diversion programs.16 The law also required the state’s new Juvenile Justice Oversight Committee to develop detailed parameters to guide the operation of the new diversion programs, ensure that the programs follow best practices, and create a data collection and analysis process to guide the development of diversion programs and to track outcomes.17

- Michigan – In November 2023, Michigan enacted a broad package of youth justice reforms that included provisions to expand the list of offenses eligible for diversion, allow the use of state funds to support diversion programming, limit periods of diversion to three months in most cases, and eliminate fines and fees for diversion and other facets of the youth justice system.18

- Massachusetts – As part of a justice reform law in 2018, Massachusetts established a new Juvenile Justice Policy and Data Board (JJPAD), which has subsequently crafted an ambitious agenda for expanding the use of diversion statewide. The JJPAD has published a model program guide for diversion19 as well as several other in-depth studies on diversion issues.20 In 2021, the state began testing its new diversion model in three counties, and it has since expanded to four additional counties,21 with plans to make the new diversion programs available to all youth statewide by 2027.22 Though participation in the first three counties has been limited thus far – 134 youth in 202223 – Massachusetts has seen a significant increase in the use of diversion statewide: From 2016 to 2022, the share of delinquency cases diverted before a case filing rose from 29% to 38%, and the share diverted before an arraignment climbed from 47% to 65%.24

- South Dakota – Passed in 2015, a comprehensive juvenile justice reform law made diversion the default option for first nonviolent misdemeanors as well as all status offenses, and it began providing local courts with a financial incentive for each young person who completes diversion.25 Since then, South Dakota has increased the number of youth who are diverted more than 50%, and it sharply reduced the failure rates of youth in diversion.26 As a result, the total number of youth completing diversion successfully has more than doubled from 970 in 2016 to 1,983 in 2022.27

- Iowa – Over the past decade, a growing number of local court jurisdictions have begun offering pre-charge diversion programs, many of them targeted specifically to reduce racial and ethnic disparities. In recent years, the state has intensified its focus on expanding diversion in several ways: funding a statewide assessment of diversion in 2019;28 making grant funds available to support local diversion programming in 2021 and again in 2023; and publishing a report in February 2023 developed by a juvenile justice task force appointed by the state’s supreme court that included recommendations to expand the use of diversion and create statewide diversion standards.29

- Harris County (Houston), Texas – Harris County has undertaken ambitious reforms of its juvenile justice system in the past five years, with an emphasis on diversion.30 From 2017 to 2021, the share of delinquency cases diverted grew from 12% to 32%, and Black youths’ share of diverted cases increased from one-fourth to nearly half.31 Harris County also has created a new multimillion-dollar funding stream to support community-based services, including diversion, for youth involved in or at risk of justice system involvement.31

- Ramsey County (St. Paul), Minnesota – As part of a community-wide “(Re)Imagining Juvenile Justice” initiative led by the county’s prosecutor, Ramsey County has empowered a new Collaborative Review Team to examine most delinquency cases before charges are filed in court and determine how best to repair the harm caused by the offense, address the needs that caused the youth to offend, and support the young person’s positive development.33 Of the 685 youth who went through this process in the first year, 41% were either dismissed or diverted to community-based programs.34 Ramsey County has decreased the share of delinquency cases formally charged in court from 60% in 2017-18 to 35% in 2021-22, and also reduced racial and ethnic disparities in diversion.35

New Rules to Mandate or Compel the Use of Diversion in Many Delinquency Cases.

A growing number of jurisdictions now have laws or practices to make diversion mandatory, routine, or presumed for many youth apprehended by police or referred to court on delinquency charges.

- In Utah, with few exceptions,36 youth referred to juvenile court for misdemeanor offenses are automatically eligible for diversion, provided they do not have two prior adjudications in juvenile court and have not had more than two failed attempts at diversion previously.37 Statewide, Utah diverted 64% of all delinquency cases referred to juvenile courts in 2023,38 up from 31% in 2015.39

- Washington state requires prosecutors to divert all youth facing first-time misdemeanor or grand misdemeanor charges.40 A 2018 reform law also expanded diversion eligibility to include many felony offenses, eliminated the cap on the number of times youth can be offered diversion, and encouraged the use of community-based diversion programs.41

- In Kentucky, a comprehensive 2014 juvenile justice reform law made diversion the presumptive option for youth accused of first-time misdemeanor offenses.42 Though it allows judges and prosecutors to override this presumption based on the circumstances of each case, the law has led to an increase in the share of juvenile cases diverted statewide from 41% in 2013 to 60% in 2020.43

- To increase and better target the use of diversion, New York City’s Probation Department devised a structured decision-making grid to help guide diversion decisions, with diversion encouraged for all youth assessed as low risk (regardless of the current offense) as well as moderate-risk youth accused of most misdemeanor offenses.44 Though the guidelines were not mandated, the use of diversion became much more targeted after the grid’s introduction: Between 2017 and 2022, the share of low-risk youth cases diverted rose from 36% to 61%, while the share of high-risk cases diverted fell from 11% to 3%. Overall, the share of cases diverted rose from 25% to 41% in these five years.45

- Since 2016 Clark County (Las Vegas), Nevada has been diverting virtually all misdemeanor offenses to a new county-run youth assessment center called The Harbor, where youth and their caregivers are interviewed and screened for a variety of needs and challenges (mental health, substance abuse, trauma, food security, and more) and then referred to relevant services in the community.46 The Harbor, which also works with many youth not involved in the justice system, has served more than 30,000 youth and families since 2016.47 Of the 1,000-plus referred on delinquency charges in 2020, just 17% had a subsequent delinquency case filed in juvenile court within three years.48

- In San Francisco, all youth misdemeanor cases and some felony cases are enrolled in a community-based diversion program that combines restorative justice (to address harms caused by the youth’s offense), plus supportive programming that can include mental health counseling, tutoring, employment, community service, life skills workshops, and other services to address needs identified in the assessment process.49

Automatic Diversion for the Youngest Youth.

There is a growing movement across the nation to raise the minimum age of juvenile court jurisdiction. As of 2016, only 18 states had any minimum age below which a child could not be prosecuted and punished in delinquency court, and no state set the minimum above age 10.50 Since then, 15 states created or increased the minimum age, and eight of these states have set the minimum age at 11 or higher for most or all offenses.51 By raising the age these states have, in effect, ensured that all children under the new age thresholds will be diverted from juvenile court for any delinquent offense they might commit.

New Diversion Initiatives for Lower-Risk Youth With Human Service Needs.

Too often, young people enter the delinquency court system not because they have committed serious offenses, but rather because they face acute needs and require support. Some have committed only status offenses such as truancy from school or running away from home, but no crimes. Others are arrested on domestic violence charges sparked by chaotic or unstable home environments. Still others suffer with serious mental health or substance use disorders. In all of these cases, formal processing in juvenile courts is unnecessary and counterproductive. As the National Center for State Courts has written: “Youth should never have to enter the juvenile justice system to access services.”52 Rather, these youth should be served outside the court system by human service agencies with expertise in addressing young people’s needs.

- In 2021, North Dakota passed a law removing youth accused of status offenses from the jurisdiction of the state’s juvenile delinquency courts.53 Instead, youth who commit only status offenses like running away, underage truancy, or alcohol possession are referred to a “Human Service Zone.”54 The law also requires schools to: make a concerted effort to work with youth who show poor attendance, rather than send them immediately to court for truancy; and handle most routine misbehavior at school through the school discipline process, rather than involving police and pressing charges.55

- In 2015, Connecticut enacted legislation removing truancy from the jurisdiction of the juvenile courts. Two years later, the state removed all other status offenses from the courts. Instead, all youth involved in status offenses are now served through Connecticut’s network of Youth Service Bureaus, which are not a part of the justice system.56

- In 2022, the Idaho legislature appropriated $6.5 million to create a network of eight new Youth Assessment Centers that will support youth with behavioral health issues outside of the formal youth justice system.57 In 2023, working with the National Assessment Center Association, the state’s Department of Juvenile Corrections is spending an additional $4.1 million to support the growth and development of the new assessment centers.58

- Since 2017, Utah’s Division of Juvenile Justice and Youth Services has created a network of 11 youth services centers that provide early intervention services to youth who might otherwise enter the justice system.59 The centers operate on a “no wrong door” approach that enables youth and families to access the full array of available services without becoming formally involved in the court system.60 Funded with dollars reinvested through savings from reduced use of residential confinement, the centers received more than $9 million as of early 2021,61 serving nearly 3,000 youth in fiscal year 2022.62

Promoting Racial and Ethnic Equity

Research overwhelmingly finds that arrest and pre-court diversion are justice system decision points with large and consequential disparities. Studies consistently find that white youth are diverted at far higher rates than comparable Black, Latinx, and Tribal youth, and these disparities in diversion can have cascading effects that lead to far larger disparities in later stages of the justice system process — most notably incarceration.5 Some jurisdictions are undertaking extensive efforts to measure and understand the factors driving these disparities in diversion and are crafting innovative solutions to reduce them. (For more information on strategies to reduce disparities in diversion, see Diversion Issue Brief #1, available April 2024.)

- In September 2021, youth justice leadership teams from seven Pennsylvania counties took part in Georgetown University Center for Juvenile Justice Reform’s weeklong certificate program on Advancing Racial Justice and Equity in youth justice. As part of the program, the teams analyzed data from their local systems and crafted plans for a “capstone project” they would undertake to reduce disparities. Six of the seven county teams focused their capstone projects on expanding diversion opportunities for youth of color and reducing disparities in diversion.64 In Allegheny County (Pittsburgh), for instance, local data showed that Black youth were five times more likely than white youth to be arrested, and then nearly 25% less likely to be diverted after arrest. In response, the local team created a new partnership with a local law enforcement agency to divert youth prior to arrest.65

- In 2021, New York state launched a Policy Equity Academy for youth justice teams from five upstate counties to understand and address disparities in diversion within their systems.66 Each county identified and developed action plans to address three equity challenges related to diversion. Several of the counties revised documents and procedures in order to reduce the share of families who refuse to participate in diversion, and multiple sites began employing “credible messengers” – adults with personal history in the justice system or other experiences in common with many youth – to enhance the effectiveness of their diversion programs.67

- Kentucky has taken several steps to reduce disparities after early results from its 2014 juvenile justice reform law showed that provisions to expand diversion were primarily benefiting white youth.68 The state revised its procedures for scheduling initial appointments to begin diversion, after data revealed that Black youth were far more likely than whites to miss these intake interviews.69 To reduce the use of overrides – where judges or prosecutors declined to divert youth on their first offenses, as the reform law recommends – state leaders and their community partners persuaded prosecutors and judges to reduce their use of overrides.70 In Jefferson County (Louisville), diversion overrides of Black youth by the county prosecutor fell 91% from 2014 to 2019.71 In Christian County, judicial overrides dropped 55% from 2018 to 2019.72 Kentucky has also provided implicit bias training to system personnel around the state.73

- In Iowa, several counties have developed youth diversion programs targeted to offenses with significant disparities. Johnson County (Iowa City) developed a diversion program for youth involved in disorderly conduct after finding that five times as many Black youth as white youth were arrested for disorderly conduct in 2012 – even though white youth in the county outnumbered Black youth by nearly 8 to 1.74 In Scott County (Davenport), youth who commit simple misdemeanors are now automatically diverted by police and directed to participate in a one-time class with a parent or guardian.75 Before this policy took effect in 2016, 82% of youth arrested for simple misdemeanors in Scott County were Black.76

- As noted above, initial results from ambitious new diversion efforts in Ramsey County (St. Paul), Minnesota and Harris County (Houston), Texas both show that these counties are not only increasing the use of diversion but also reducing disparities. In Ramsey County, for instance, Black youth were 39% of successful diversion cases in 2017-2018, before recent reforms were instituted, but 53% of successful diversions in 2021-22.34

Improving Diversion Practices

Young people’s success is affected not only by whether or not their cases are diverted, but also by how their cases are handled once diverted. Many jurisdictions have been making encouraging progress in recent years by adopting several promising reform strategies.

Increasing Momentum for Restorative Justice Diversion.

Among the most promising recent developments in youth diversion is the growing focus on restorative justice alternatives to formal court processing. Restorative justice diversion programs require youth to focus on and repair the harm caused by their misconduct, and often include face-to-face meetings with victims. This approach offers several advantages beyond those of other approaches to diversion. First, restorative justice diversion directly addresses the needs of victims, leading to far higher victim satisfaction with the justice process.78

Also, surveys consistently find that the overwhelming majority of accused youth and parents who participate in a restorative justice process have positive experiences.79 Many experts argue that the restorative justice process – engaging youth in meaningful conversations with those they’ve harmed, and participating in a process to craft a plan to repair the harm – has important developmental benefits for youth in terms of building empathy.80 Finally, restorative justice offers clear advantages over other diversion strategies in terms of public opinion and political support; indeed, it can be argued persuasively that restorative justice processes offer more meaningful accountability than traditional courts.

As the director of one Colorado restorative justice diversion program explained, “To sit down across the table from someone whom you’ve harmed and work to make a repair is infinitely more difficult than to stand in front of the judge and say nothing.”81 (For more information on the promise of restorative justice diversion, see Diversion Issue Brief #2, available April 2024.)

- Colorado has focused intensively on restorative justice diversion over the past decade.82 The state has enacted a series of laws to guide and encourage the use of restorative justice diversion, and it funded and evaluated a pilot program from 2013 to 2020.83 Today, restorative justice diversion programs operate in half of the state’s court districts,84 and in some districts restorative justice is now the default option for many or most delinquency cases.85 For instance, in the Boulder area more than half of youth referred to court are now diverted to restorative justice programs, and more than 90% of participants complete the program. Less than one in 10 completers commit a new offense within one year, and 99% of victims who participated reported being satisfied with the process.86

- Nebraska has invested heavily in restorative justice.87 Specifically, the state’s Victim-Youth Conferencing program works with youth issued citations by law enforcement in schools, as a diversion option for prosecutors in lieu of formal court processing, and for youth after adjudication or as part of probation.87 One evaluation found that the program served nearly 700 youth from January 2018 through June 2021, with low recidivism and high satisfaction from participating victims, youth, and parents.89

- Minnesota created an Office of Restorative Practices in 2023 to promote the use of restorative justice, including for juvenile diversion.90 The state also set aside $4 million per year to support restorative justice programming around the state.91

- Illinois, Maine, and Oregon have enacted laws in recent years to protect the confidentiality of restorative justice proceedings in order to ensure that admissions of guilt made as part of the restorative process cannot later be used against youth in court.92 A lack of clear confidentiality protections in restorative justice is a concern raised by some advocates who fear the process could result in self-incrimination.93

Expanding the Use of Pre-Arrest Diversion.

Being arrested during adolescence has a powerful negative effect on future success, even if the young person is subsequently diverted from court.94 Arrests substantially reduce the likelihood that youth will complete high school school and increase the chances they will be arrested for future offenses.5 Pre-arrest diversion offers a promising avenue to boost youth success.

- Los Angeles County, California approved plans in 2017 to develop a county-wide network of community-based diversion programs and to begin offering pre-arrest diversion for up to 80% of youth accused of delinquency offenses.96 Though the progress has been slower than anticipated,97 the county is continuing to roll out the plan under the auspices of its new Department of Youth Development. A first round of grants were awarded in 2019 to support programs in eight locations. Since then, the county has added more locations with the goal of offering pre-arrest diversion programs countywide by 2024.98 As of June 2023, the diversion programs had served nearly 2,500 youth.99

- Florida offers civil citations as an alternative to arrest and formal court processing for youth apprehended for misdemeanor offenses. First introduced in Miami-Dade County in 1997, the use of civil citations has expanded steadily since the state began supporting statewide implementation in 2011. Nearly 12,000 Florida youth received civil citations in the 2022-23 fiscal year.100 State data analyses consistently find that youth offered civil citations are less likely to re-enter the justice system on subsequent charges than youth who are arrested and subsequently diverted, and they are far less likely to re-enter the system than those who are arrested and have their cases formally processed in delinquency court.101 Statistical analyses show that, even after controlling for young people’s backgrounds, offending histories, and other documented risk factors, civil citations lead to a significant reduction in the likelihood of rearrest.101

- Shelby County (Memphis), Tennessee, opened the Youth and Family Resource Center in April 2022 to work with youth who might otherwise be arrested for any of 12 low-level offenses. Rather than arresting youth, law enforcement officers write a summons requiring the young person and a caregiver to visit the center, which is operated by the county’s Division of Community Services and is not affiliated with the court. There, youth and their families take part in a detailed assessment and then work with staff to develop an action plan to build on the young person’s strengths, address needs, and access relevant programs and services in the community. As part of the diversion, youth are required to undertake this assessment process, but once the plans are completed participation in the specified activities is voluntary.103

Increasing the Success Rates of Youth in Diversion.

A detailed 2019 study of youth diversion reported that in most jurisdictions across the country, somewhere between 10% and 30% of youth initially diverted from court typically fail diversion and later have their cases formally petitioned. In some courts, the study found, diversion failure rates can run as high as 50%.104 Given the poorer results associated with formal involvement in court, as well as the evidence that youth of color are less likely than their white peers to be diverted and to complete diversion successfully, states and localities should prioritize strategies to minimize the number of diversion failures. Several strategies in this regard show promise.

- As part of its 2014 reform law, Kentucky required each judicial district to create a team to assist youth with high needs who don’t make progress toward completing diversion. An evaluation found that these teams improve the success rates of youth served.105

- As part of the Immediate Intervention Program established in its 2016 reform law, Kansas now requires every county to create a multidisciplinary team to support any youth who has difficulty completing diversion successfully.106

- South Dakota has employed financial incentives to improve the completion rates of diverted youth. The state’s 2015 reform law offers counties $250 for each successful diversion. Since the law’s passage, the success rate of diverted youth has jumped from 69% in 2016 to 88% in 2022.107

- Several states and localities have reduced or eliminated fees required to participate in diversion and other facets of the youth justice system. These fees can be a significant barrier to successful completion of diversion, and they are especially problematic for youth and families of color.108 According to Debt Free Justice, an advocacy organization fighting to eliminate fines and fees in youth justice, nine states have fully abolished fines and fees (or never charged them), and another 12 states have eliminated some or most fees.109 For instance, Indiana’s 2022 juvenile justice reform law specifically eliminated fees for diversion.110

- Santa Cruz County, CA111 and Davidson County (Nashville), Tennessee5 are among the jurisdictions that have adopted a practice of never returning youth to court for failing diversion, heeding the recommendations of the Annie E. Casey Foundation113 and the Center for Children’s Law and Policy.114 Likewise, Harris County (Houston), Texas rarely returns youth to court for failing to fulfill diversion rules and requirements.115

Improving Data Collection and Analysis

More and more states and localities are recognizing the need to compile more data and conduct better data analysis on diversion in order to detect gaps and problems in current diversion practices, address disparities, and identify opportunities for improvement. (For more information about improving data collection and analysis, see Diversion Issue Brief #3, available April 2024.)

- In 2019, Massachusetts’ new Juvenile Justice Policy and Data Board (JJPAD) prepared a 40-page report documenting how the “lack of available data often impedes our ability to make data-informed decisions about policy and practice.”116 The report identified four critical data gaps specifically related to diversion.117 Three years later, JJPAD published a follow-up study showing that while the state had made “significant progress improving system data availability” since 2019, there remained “critical pieces of juvenile justice data unavailable” – many of which related to diversion.118

- Juvenile justice reform laws enacted in Indiana,119 Utah,120 and Colorado121 since 2022 have all included ambitious new data collection and reporting requirements related to diversion. For instance, Indiana’s new law created a juvenile justice oversight board with responsibility to “develop a plan to collect and report statewide juvenile justice data … [and] [e]stablish a minimum set of performance and data measures that counties shall collect and report annually, including equity measures.” In Iowa, a juvenile justice task force assembled by the state’s supreme court recommended several steps in 2023 to improve data collection as part of the state’s efforts to expand the use of diversion.122

- A growing number of jurisdictions – such as Florida,123 Georgia,124 Iowa,125 Kansas,126 and Utah127 – are creating data dashboards to track results of their diversion programs.

Conclusion

Taken together, the many reform efforts described in this issue brief suggest the beginnings of what may become – and should become – a fundamental shift in America’s approach to youth justice.

Gradually but unmistakably, state and local leaders across the country, regardless of region or ideology or political party in power, are recognizing and acting on the evidence that arresting youth and prosecuting youth in the court system is often counterproductive.

And the momentum continues. “I am seeing more energy around diversion than ever before,” says Tiana Davis, former policy director of equity and diversion at the Center for Children’s Law and Policy, “especially around community-focused diversion.”128

| 1. | The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (July 2022). Talking about Youth Probation, Diversion, and Restorative Justice: A Messaging Toolkit. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Mendel, R. (2022). Diversion: A Hidden Key to Combating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Juvenile Justice. The Sentencing Project. |

| 3. | Mears, D. P., Kuch, J. K., Lindsey, A.M. Sienneck, S. E., Pesta, G. B. Greenwald, M. A., & Blomberg, T. G. (2016). Juvenile Court and Contemporary Diversion: Helpful, Harmful, or Both? Criminology & Public Policy 15(3), 953-981. |

| 4. | Mendel (2022), see note 2; Cauffman, E., Beardslee, J., Fine, A., Frick, P.J., & Steingberg, L. (2021). Crossroads in juvenile justice: The impact of initial processing decision on youth five years after first arrest. Development and Psychopathology 33, 700-713. 10.1017/S095457942000200X |

| 5. | Mendel (2022), see note 2. |

| 6. | Mendel (2022), see note 2. |

| 7. | Mendel (2022), see note 2. |

| 8. | Mendel (2022), see note 2. |

| 9. | Kansas’ 2016 Juvenile Justice Reform. (2017). Pew Charitable Trusts. |

| 10. | Juvenile Justice System; SB 367 (Legislation Summary) (2016). Kansas State Legislature. |

| 11. | Juvenile Justice Oversight Report Dashboard: IIP Youth Ordered to By Gender (n.d.). Kansas Juvenile Justice Oversight Committee. |

| 12. | 2022 Annual Report. (2022). Kansas Juvenile Justice Oversight Committee. |

| 13. | Immediate Intervention Program Standard IIP-04-113: Discharge Requirements (Amended May 22, 2023). Kansas Department of Corrections- Division of Juvenile Services. |

| 14. | McCormack, A., Ribsam, J.E., & Sellars, J. (2023, May 26). New Hampshire’s juvenile justice transformation: Radically reducing the need for court, probation, placement, and confinement [Conference session]. Coalition for Juvenile Justice National Conference, Washington, DC, USA. |

| 15. | McCormack, A., Ribsam, J.E., Jr. & Sellars, J. (2023), see note 14. |

| 16. | Vorpahl, A. (2022). Explainer: The Significance of Indiana’s IOYouth Bill. Council of State Governments Justice Center. |

| 17. | Diversion Report. ( 2023). Youth Justice Oversight Committee. |

| 18. | Justice for Kids and Communities Legislative Package. (n.d.) Michigan Center for Youth Justice; Gibbons, L. (2023). Michigan lawmakers vote to end most juvenile court fees, citing harms. Bridge Michigan. |

| 19. | Massachusetts Juvenile Justice Policy and Data Board Community Based Interventions Subcommittee. (2021). Massachusetts Youth Diversion Program: Model Program Guide. Massachusetts Juvenile Justice Policy and Data Board. |

| 20. | Massachusetts Juvenile Justice Policy and Data Board Community Based Interventions Subcommittee. (2019). Improving Access to Diversion and Community-Based Interventions for Justice Involved Youth. Massachusetts Juvenile Justice Policy and Data Board; Massachusetts Juvenile Justice Policy and Data Board Community Based Interventions Subcommittee. (2019). Early Impacts of “An Act Relative to Criminal Justice Reform; Massachusetts Juvenile Justice Policy and Data Board; Massachusetts Juvenile Justice System. (2022). Massachusetts Juvenile Justice Policy and Data Board; Racial and Ethnic Disparities at the Front Door of Massachusetts’ Juvenile Justice System: Understanding the Factors Leading to Overrepresentation of Black and Latino Youth Entering the System (2022). Massachusetts Juvenile Justice Policy and Data Board. |

| 21. | Massachusetts Office of the Child Advocate. (2023). The Massachusetts Youth Diversion Program: Impact Report |

| 22. | Sibanda, N., Chief of Staff of the Massachusetts Department of Youth Services, personal communication, October 26, 2023. |

| 23. | Massachusetts Office of Child Advocate (2023), see note 21. |

| 24. | Massachusetts Juvenile Justice System (2022), see note 20; Improving Access to Diversion and Community-Based Interventions for Justice-Involved Youth (2019), see note 20. |

| 25. | South Dakota’s 2015 Juvenile Justice Reform. (2016). Pew Charitable Trusts. |

| 26. | Juvenile Justice: Public Safety Improvement Act 2021 Annual Report. (2022). South Dakota Juvenile Justice Oversight Council; South Dakota Needs Continued Support for Juvenile Diversion. (2022). South Dakota Kids Count. |

| 27. | South Dakota Juvenile Justice Oversight Council (2022), see note 26; and South Dakota Needs Continued Support for Juvenile Diversion. (2022). Kids Count South Dakota. |

| 28. | Iowa Pre-charge Diversion Toolkit. (n.d.) Center for Children’s Law and Policy. |

| 29. | Report and Recommendations. (2023). Iowa Supreme Court Juvenile Justice Task Force. |

| 30. | Fuller, C., Meyer, A., & Ananthakrishnan, V. (2022). Process Matters: Reflections from the Development of Harris County’s Youth Justice Community Reinvestment Fund and Recommendations to Guide Future Efforts. Columbia Justice Lab. |

| 31. | Fuller, Meyer, & Ananthakrishnan (2022), see note 30. |

| 32. | Fuller, Meyer, & Ananthakrishnan (2022), see note 30. |

| 33. | Beckman, K., Steward, D., Gacad, A., Espelien, D., & Shlafer, R. (2023). (Re)Imagining Justice for Youth: Year One Evaluation Report. Healthy Youth Development • Prevention Research Center, Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN. |

| 34. | Beckman et al. (2023), see note 33. |

| 35. | Beckman et al. (2023), see note 33; RJY Dashboard. (2022). Ramsey County Attorney’s Office. |

| 36. | The only exceptions to this rule are weapons offenses, reckless endangerment, and a handful of other serious misdemeanor charges. Section 303.5 Preliminary inquiry by juvenile probation officer — Eligibility for nonjudicial adjustment, Utah Juvenile Code, Section 6, Part 3, Section 303.5 (2023). |

| 37. | Utah Juvenile Code Section 6, Part 3, Section 303.5 (2023), see note 36. |

| 38. | Fiscal Year 2023 Juvenile Justice Reform Report. (2023). Utah Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice. |

| 39. | Fiscal Year 2019 Juvenile Justice Reform Report. (2019). Utah Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice. |

| 40. | Washington State Engrossed Substitute Senate Bill 6550. (2018). Washington State Legislature. |

| 41. | Washington State Engrossed Substitute Senate Bill 6550 (2018), see note 40. |

| 42. | Harvell, S. (2020). Kentucky Is Succeeding in Keeping Youth Out of the Juvenile Justice System. Urban Institute. |

| 43. | Bingham, R. & Palmer, E.L. (2023, July 17). Diverting Youth From the Justice System. [Conference Session]. National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges Annual Conference, Baltimore, MD, United States. |

| 44. | Bermudez, A., former Chief of the New York City Probation Department, personal communication September 7, 2023; Bermudez, A., personal communication, October 2023. |

| 45. | Fuleihan, D. & Thamkittikasem, J. Mayor’s Management Report Fiscal Year 2021. (2021). City of New York; Grillo, L. & Steinberg, D. Mayor’s Management Report Fiscal Year 2022. (2022). City of New York. |

| 46. | “The Harbor: A Safe Place for Guidance.” (Summer 2023). NAC Spotlight. National Assessment Center Association. |

| 47. | “The Harbor: A Safe Place for Guidance.” (Summer 2023), see note 46. |

| 48. | Wright, C., Deputy Director of the Clark County Department of Juvenile Justice Services, personal communication, November 7, 2023. |

| 49. | Coleman, D., Buren, H., & Beach, R. (2022). Community-Based Juvenile Justice in San Francisco: Huckleberry Youth Programs’ Community Assessment & Resource Center (CARC). [PowerPoint slides] Presentation to the Juvenile Probation Commission. Huckleberry Youth Programs; Buren, H., Director of the Huckleberry Community Assessment & Resource Center (CARC), personal communication, October 5, 2023). |

| 50. | Zang, A. U.S. (2017). U.S. Age Boundaries of Delinquency 2016. Juvenile Justice Geography Policy, Practice, Statistics. |

| 51. | The states with a higher minimum age in 2023 than in 2016 include: Arizona, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Utah, and Washington; Zang (2017), see note 50; Brief: Charting U.S. Minimum Ages of Jurisdiction, Detention, and Commitment. (2023). National Juvenile Justice Network. |

| 52. | Behavioral Health State Court Leadership Briefing. (2022). Juvenile Justice Mental Health Diversion: Guidelines and Principles. National Center for State Courts. |

| 53. | Agus-Kleinman, J. & Watson, S. (2021). North Dakota Modernizes Juvenile Justice System. Council of State Governments Justice Center. |

| 54. | North Dakota. (2022). Human Service Zones. North Dakota Health and Human Services. |

| 55. | Kringlie, K (2022). North Dakota Juvenile Justice Reform: Lessons Learned. [PowerPoint slides]. |

| 56. | Why Status Offense Laws in Connecticut Have Changed (2019). Tow Youth Justice Institute. |

| 57. | Youth Assessment Centers in Idaho. (2023). Idaho Department of Youth Corrections and National Assessment Center Association. |

| 58. | Youth Assessment Centers. (last updated November 21, 2023). Idaho Department of Youth Corrections. |

| 59. | Utah Department of Health & Human Services. (n.d.). Juvenile Justice and Youth Services [Fact Sheet]. |

| 60. | Juvenile Justice Pipeline and the Road Back to Integration: Hearing before the House of Representatives Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security of the Committee on the Judiciary. 117th Cong. (2021) (Testimony of Brett Peterson). |

| 61. | Data shows Utah’s juvenile justice reform is working. (2021). Fox 13, Salt Lake City. |

| 62. | Utah’s Juvenile Justice System Fiscal Year 2022 Summary. (2022). Utah Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice. |

| 63. | Mendel (2022), see note 2. |

| 64. | Ogle, M.R. (2023). Advancing Racial Equity in Pennsylvania’s Youth Legal System. Georgetown University Center for Juvenile Justice Reform and Stoneleigh Foundation. |

| 65. | Ogle (2023), see note 64. |

| 66. | Medelis, K.P. & Victorio, V. (July 15, 2021). New York project aims to narrow gap between minority versus white juvies sent to community programs, not prison. Juvenile Justice Information Exchange. |

| 67. | Lopes, G., & Irons, D., from Youth Justice Institute, personal communication, November 7, 2023; Deame, T., & Conley, K., from NYS Division of Criminal Justice Services, personal communication, November 7, 2023. |

| 68. | Howard, K. (2018). Kentucky Reformed Juvenile Justice, And Left Black Youth Behind. Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting. |

| 69. | R. Bingham, Director of Family and Justice Services, Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts, personal communication, April 15, 2022. |

| 70. | Bingham (2022), personal communication, see note 69; Palmer, E., & Bingham, R. (2021). Don’t Hate the Player, Hate the Game: The Importance of Systemic Change to Address Racial and Ethnic Disparities. The Juvenile Justice Update, 27(1). |

| 71. | Bingham, R. & Palmer, E. (2022, November 1-2). Utilizing Implementation Science to Structure R/ED Efforts [Conference Session] Coalition for Juvenile Justice Racial and Ethnic Disparities Conference. |

| 72. | Bingham, R. & Palmer, E. (2022, November 1-2), see note 71. |

| 73. | Palmer, E., & Bingham, R. (2021), see note 70. |

| 74. | The [Cedar Rapids] Gazette (June 26, 2014). Johnson County diversion program to offer youth a chance to avoid court. |

| 75. | Bala, N. & Mooney, E. (2019). Promoting Equity With Youth Diversion. R Street Institute. |

| 76. | Bala & Mooney (2019), see note 75. |

| 77. | Beckman et al. (2023), see note 33. |

| 78. | Strang, H., Sherman, L. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., Woods, D. & Ariel, B. (2013). Restorative Justice Conferencing (RJC) Using Face-to-Face Meetings of Offenders and Victims: Effects on Offender Recidivism and Victim Satisfaction. A Systematic Review. Campbell Systematic Review; Seacrest, L. (September, 2023). Justice for All: How Restorative Justice Mutually Benefits Victims and Youth. R Street Institute. |

| 79. | Windler, C. & Nunes, A.P. (2018). Restorative Justice in Juvenile Diversion: An Evaluation of Programs Receiving Colorado. Omni Institute; Baliga, S., Henry, S., & Valentine, G. (2017). Restorative Community Conferencing: A study of Community Works West’s restorative justice youth diversion program in Alameda County. Community Works West & Impact Justice. |

| 80. | Choi, J. J., Green, D. L., & Gilbert, M. J. (2011). Putting a human face on crimes: A qualitative study on restorative justice processes for youths. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 28(5), 335–355.; Kuehn, S., Yarnell, J., & Champion, D. R. (2014). Juvenile probationers, restitution payments, and empathy: An evaluation of a restorative justice based program in northeastern Pennsylvania. International Journal of Criminology and Sociology 3, 377-387. |

| 81. | Sawyer, L., Serres, C., & Holt, J. (December 29, 2022). Laying Down the Law for Troubled Youths: Minnesota’s juvenile justice system is broken. Colorado shows how it could be better. StarTribune. |

| 82. | Sliva, S., Porter-Merrill, H. E.,& Lee, P. (2019). Fulfilling the Aspirations of Restorative Justice in the Criminal System? The Case of Colorado. Kansas Journal of Law and Public Policy 28, 457-504. |

| 83. | Colorado Juvenile Diversion Evaluation. (2020). OMNI. |

| 84. | Courtney, L. (2022). The Restorative Justice and Diversion Program: Colorado 20th Judicial District Attorney’s Office (Boulder County, Colorado). Urban Institute. |

| 85. | Sliva, S. M. & McClain, T. M. (2021). Mapping the Path to Restorative Justice Diversion: Lessons from HB13-1254, Colorado’s Legislated Pilot of Pre-File Restorative Justice Diversion for Juveniles. Colorado Restorative Justice Coordinating Council. |

| 86. | Golden, A. (March 3, 2023). More than half of juvenile cases diverted by DA’s office. Longmont Leader. |

| 87. | Seacrest, L. (September, 2023), see note 78. |

| 88. | Seacrest, L. (September, 2023), see note 78. |

| 89. | Jimenez, C. A. (2021). Victim Youth Conferencing Evaluation. State of Nebraska Judicial Branch, Office of Dispute Resolution. |

| 90. | Serres, C. & Sawyer, L. (May 15, 2023). Minnesota lawmakers OK ‘transformative’ juvenile justice package. Minneapolis Star-Tribune. |

| 91. | State of Minnesota Bill S2909-4, § 19.1-19.33. (2023). The law allocates $4 million each in fiscal year 2024 and FY 2025 to help local jurisdictions establish and operate restorative justice programs, then $2.5 million per year beginning in FY 2026. |

| 92. | National Conference of State Legislators (2022). Juvenile Justice: Young People and Restorative Justice. |

| 93. | Ikpa, T. (2007). Balancing Restorative Justice Principles and Due Process Rights in Order to Reform the Criminal Justice System. Washington University Journal of Law and Policy 24, 301-325. |

| 94. | Beardslee, J., Miltimore, S., Fine, A., Frick, P., Steinberg, L., & Cauffma, E. (2019). Under the radar or under arrest: How is adolescent boys’ first contact with the juvenile justice system related to future offending and arrests? Law and Human Behavior, 43(4), 342-357; Nadel, M., Bales, & W., Pesta, G. (2019). An assessment of the effectiveness of civil citation as an alternative to arrest among youth apprehended by law enforcement. Florida State University. |

| 95. | Mendel (2022), see note 2. |

| 96. | Fremon, C. (2017). Los Angeles Board Of Supervisors Votes To Launch ‘Historic’ Juvenile Diversion Plan. Juvenile Justice Information Exchange. |

| 97. | Los Angeles County Department of Youth Development Diversion Quarterly Dashboard: June 30, 2023. (2023). Los Angeles County Department of Youth Development. |

| 98. | Updated Department of Youth Development Diversion Data Dashboard: Youth Referred to DYD Programs by April 1, 2023. (2023). Los Angeles County Department of Youth Development. |

| 99. | Los Angeles County Department of Youth Development Diversion Quarterly Dashboard: June 30, 2023 (2023), See note 97. |

| 100. | Civil Citation & Other Alternatives to Arrest Dashboard. (2021). Florida Department of Juvenile Justice. |

| 101. | Nadel et al (2019), see note 94. |

| 102. | Nadel et al (2019), see note 94. |

| 103. | S.Bromley, Deputy Director – Justice Programs, Shelby County Division of Community Services, & A. Kalb, Director of the Shelby County Youth and Family Resource Center, personal communication, October 6, 2023. |

| 104. | Kroboth, L., Purewal Boparai, S., & Heller, J. (2019). Advancing Racial Equity In Youth Diversion. Human Impact Partners. |

| 105. | Harvell, S., Sakala, L., Lawrence, D. S., Olsen, R., & Hull, C. (2020). Assessing Juvenile Diversion Reforms In Kentucky. Urban Institute Justice Policy Center. |

| 106. | Revised Kansas Juvenile Justice Code, Article 23 § 46 (2019). |

| 107. | Juvenile Justice: Public Safety Improvement Act 2021 Annual Report (2022), see note 26. South Dakota Needs Continued Support for Juvenile Diversion (2022), see note 26. |

| 108. | Feierman, J., Goldstein, N., Haney-Caron, E., & Fairfax Columbo, J. (2016) Debtors’ Prison for Kids? The High Cost of Fines and Fees in the Juvenile Justice System. Juvenile Law Center. |

| 109. | Our Impact. (2021). Debt Free Justice. |

| 110. | Eliminated Some Fees and Some Fines: Indiana. (2021). Debt Free Justice. |

| 111. | Mendel, R. (2018). Transforming Juvenile Probation: A Vision for Getting it Right. Annie E.Casey Foundation. |

| 112. | Mendel (2022), see note 2. |

| 113. | Mendel (2018), see note 111. |

| 114. | Iowa Pre-Charge Diversion Toolkit (2019), see note 28. |

| 115. | H. Gonzalez, Executive Director of Harris County Juvenile Probation Department, personal communication, November 17, 2023; Dana Legler, Assistant District Attorney, Harris County, personal communication, November 17, 2023. |

| 116. | Massachusetts Juvenile Justice Policy and Data Board Data Subcommittee. (2019). Improving Access to Massachusetts Juvenile Justice System Data. Massachusetts Juvenile Justice Policy and Data Board. |

| 117. | Improving Access to Massachusetts Juvenile Justice System Data (2019), see note 116. |

| 118. | Massachusetts Juvenile Justice Policy and Data Board Data Subcommittee. Improving Access to Massachusetts Juvenile Justice System Data: An Update of the 2019 Report. (2022). Massachusetts Juvenile Justice Policy and Data Board. |

| 119. | Vorpahl (2022), see note 16. |

| 120. | House Bill 304 Summary (2023). Utah Juvenile Justice Oversight Committee. |

| 121. | Reduce justice-involvement for young children. Colorado General Assembly, HB 23-1249. (2023). |

| 122. | Iowa Supreme Court Juvenile Justice Task Force (2023), see note 29. |

| 123. | Interactive Data Reports. (2021). Florida Department of Juvenile Justice. |

| 124. | Georgia Juvenile Justice Data Clearinghouse. (n.d.) Georgia Criminal Justice Coordinating Council |

| 125. | Easy Access to Juvenile Court Data. (last updated May 11, 2017). Criminal and Juvenile Justice Planning, Iowa Department of Human Rights. |

| 126. | Kansas Immediate Intervention Program Data [dashboard]. (2023). Kansas Department of Corrections. |

| 127. | Nonjudicial Adjustments: Fiscal Year 2023 Juvenile Justice Reform Report. (2023). Utah Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice. |

| 128. | Tiana Davis, personal communication, September 22, 2023. |